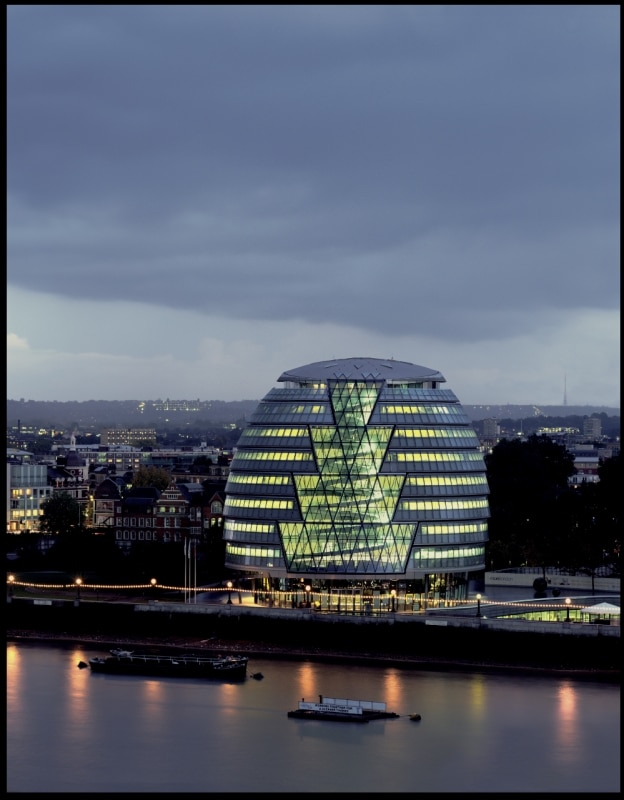

The early noughties characterised a decade of statement buildings. There was the London Eye, designed by Marks Barfield Architects and built in 2000 for an intended short stay but remaining as a symbol of Millennium optimism and engineering prowess. There was Rafael Viñoly’s 20 Fenchurch Street, conceived in the mid-2000s and manifesting as the stocky ‘Walkie Talkie’ in 2014. There was Foster’s 30 St Mary Axe—known as the ‘Gherkin’—appearing in 2002 in a much quieter City of London, eventually joined across the river by a comrade in Renzo Piano’s towering Shard of glass, built between 2009 and 2012.

Nicknamed buildings rose up beyond London: Calatrava’s City of Arts and Sciences—also known as L'Hemisfèric—introduced visual opera to the heart of Valencia. Zaha’s MAXXI Museum in Rome became the apex of sculptural architecture the world over. In Dubai, the Burj Al Arab by Tom Wright insisted luxury hospitality should come in the guise of a colossal sailing ship, joined in formal unison by the waves of Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Centre, built in Los Angeles in 2003.

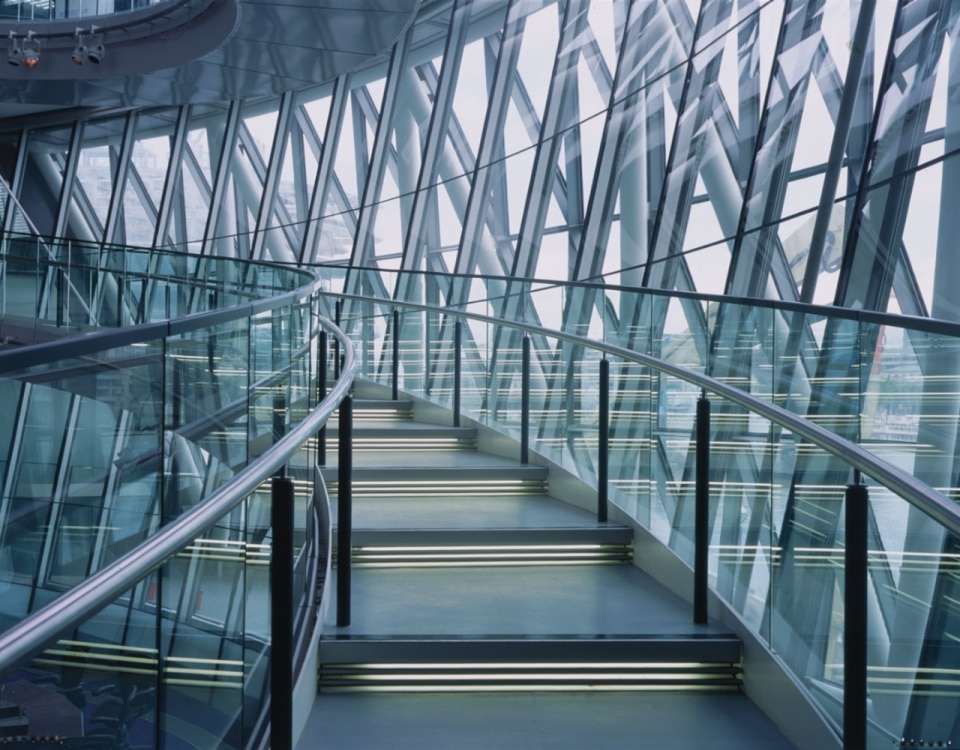

A year earlier, one of the youngest to join the starchitect band was Foster + Partners’ design for London’s City Hall headquarters, today known as 110 The Queen’s Walk. The building received a few nicknames when it first took form on London’s Southbank—the ‘onion’, the ‘helmet’, even the ‘glass gonad’—all alluding to its tilted, wide, bulbous shape. In its original format, the building rose to about 45 metres, included 10 storeys above ground, and was dominated internally by a vast, helical atrium—similar in experience to the slowly ascending spiral of New York’s Guggenheim Museum.

That kind of dedicated gestural motif was called for by the building’s use and architectural nomenclature. It was built specifically as the headquarters for the Greater London Authority (GLA), the governing body for London, which was created in 2000. Space, therefore, could be ‘wasted’ on a degree of ceremony.

Today it is being redeveloped by St Martins Property Investments Limited (SMPL)—the Kuwaiti property group that owns the More London estate opposite and around the building, also designed by Foster + Partners. The redevelopment was approved by London’s Southwark Council in 2024, and construction on the building is currently underway. The redesign is being led by global giant Gensler, working with landscape and engineering partners LDA Design and Waterman. Core changes will be the replacement of the building’s glass façade—currently being removed as though theatre in view of hundreds of passers-by—and eventually replaced with a more energy-efficient envelope. The redesign’s second major move will be to change the building’s original shape, widening its base to form more of a ‘tea cosy’ shape than a helmet. This will optimise internal floorplates.

The GLA moved out of the building a while ago—it has been vacant for about four years. In its new life, the building will hold office space on upper levels, and retail, food and beverage at ground level. The proposed changes aim to “create a forward-looking, mixed-use destination,” according to its official description, one that will “generate employment opportunities and increase tourism footfall”. Gensler cites principles of reuse, material circularity, passive design, biodiversity, and inclusivity as the building’s new drivers.

Visuals of the redesign show it as a rotund and sparse version of Milan’s Bosco Verticale. Like many refurbishment projects, green spills out of the edges of 110 The Queen’s Walk in the form of planted terraces and balconies that constitute the project’s bio-diversity ambition. Like its shape, its use is intended to be wider—responding to the familiar mixed-use function of many regenerated buildings.

Gone are the days where landmark buildings were used for just one thing—and perhaps rightly so. In terms of operational carbon, spending emissions on many uses at once is less sinful than spending them on mono-functional spaces. Likewise, the privilege of lofty atria and sweeping stairwells no longer holds water in a future of low carbon construction. Today’s architecture must save on carbon expenditure, which often doubles as maximisation of floorspace, and ergo, profit.

All for the good of a less showy, more democratic city. Yet, like much of post-20th century heritage, the confident form-making of the early 2000s might become sorely missed once it is edited out of recognition. The watering down of architectural identity may be what works in a practical sense, and what emblematises a more stylistically polyphonous age. But it won’t result in many nickname-able buildings.

Opening image: Gensler’s refurbishment and revitalization of the vacant building at 110 The Queen’s Walk, formerly known as City Hall. Courtesy Gensler