Every major breakthrough in the history of design has started with something that, at least at the beginning, seemed marginal. This was the case with parametric architecture in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which many perceived as an exercise for a select few—made of fluid forms, relational surfaces, and geometries too complex to appear feasible. Yet over time, that logic — form as the result of a system rather than a gesture — became embedded in software, processes, and working habits, until it became an integral part of contemporary design practice.

A similar dynamic has recently repeated with generative AI. Since 2022, tools like Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and DALL·E have introduced the ability to create images from text. Impossible architectures, unrealistic cities, and highly detailed speculative worlds have begun to fill our feeds, becoming useful material for expressing a concept, entering competitions, or building presentations.

Despite their impact, these tools remained anchored in representation. And this is where world models come in.

Pictures are no longer enough

While all the tools mentioned operate on the level of images, they are far from equivalent. In 2021, DALL·E introduced a radical shift: an image could literally be written. Midjourney, released to the public in 2022, turned that possibility into a distinct, instantly recognizable aesthetic, spreading the idea of AI as a machine for imagination rather than a simple graphic generator. Around the same time came Stable Diffusion, whose open-source model broadened access to image generation reconstructed from the “noise” of minimal visual signals, engaging far wider communities.

In February 2024, OpenAI launched Sora, capable of producing not isolated frames but continuous videos, with credible camera movements, consistent depth of field, and a visual continuity reminiscent of a film crew. The most recent version, released in 2025, further stabilized surfaces, volumes, and object interactions, reducing artifacts and oscillations.

Yet despite the impact, the underlying operation remains the same: these are models that learn and recombine visual patterns — not processes.

A video may seem physically plausible, convincing, even exciting, but this does not mean that the model understands the dynamics governing what we see

A video generated by Sora may look physically plausible, convincing, even moving, but that does not mean the model truly understands the dynamics behind what we see. It delivers pixel-level coherence, not physical or causal coherence. And as long as a system remains a visualization tool, it can expand the imaginary, generate variations, open up possibilities — but it cannot simulate effects, risks, impacts, or emergent behaviors within an environment. It cannot predict what happens when multiple factors interact in a real space, nor can it meaningfully contribute to the decisions that guide a project. This is a clear limitation, especially when it comes to architecture, urban planning, and design.

Unlike generative visual models, world models do not produce images of the world — they produce worlds that actually work. They do not generate a scene that merely looks realistic: they generate the internal logic that makes it possible — how light spreads, how a crowd distributes itself, how an object falls, how a flow changes direction.

World models, in a nutshell

In other words, world models do not imitate the appearance of a phenomenon — they learn its rules. This is also because they are not born in the world of creativity, nor in that of visual representation. They come from a completely different lineage: robotics, and the long-standing attempts to teach machines how an environment evolves by observing it, rather than by receiving instructions programmed by an engineer. The idea appears in Jürgen Schmidhuber’s early work on predictive learning in the 1990s, and takes shape throughout the 2010s with research from DeepMind, OpenAI, and the labs working on autonomous driving.

Waymo, the Alphabet company developing driverless vehicles, is perhaps the most immediate example. Its cars continuously read their surroundings through lidar, radar, and cameras, turning what they capture into an internal simulation of space in which every pedestrian, cyclist, or vehicle has a likely trajectory. They do not know traffic rules in advance — they learn them by observing, evaluating thousands of micro-futures as they move. It’s exactly what a human would do, but with an incomparably broader predictive capacity.

Generative models mimic the appearance of a phenomenon. World models learn its rules

In robotics, this ability to hallucinate plausible futures has become essential, because it allows a robot to learn how to manipulate an object without repeating thousands of real attempts. The same logic underpins models like MuZero, developed by DeepMind in 2019, which learns the rules of a system even when no one knows them in advance, or Dreamer, which enables an agent to build an internal model of the world and use it to imagine future scenarios.

This is a very different approach from traditional simulation engines, where every physical detail had to be hand-coded, as in earlier generations of video games. If a world model observes long enough how a crowd moves through a station, it can predict trajectories and patterns even under conditions it has never seen before; and if it observes how traffic builds up over the course of a day, it can anticipate congestion or deviations.

Why they will change the field of design

For architects, designers, urban planners, and anyone working with space, world models represent a substantial shift. They make it possible to observe environments that do not yet exist and study them as dynamic systems. One can see how a crowd distributes itself in an atrium during a peak influx, how a courtyard accumulates or dissipates heat in summer, how mobility changes when a street axis is modified, or how the microclimate of a neighborhood evolves with the introduction of a linear park. Even interiors become environments to be analyzed through their behavior, following patterns of use over time.

After all, design has always relied on the ability to anticipate the effects of a decision, but even the most expert foresight can run into structural limits. This is why urban planning remains particularly vulnerable to unintended side effects. History makes this clear: from the collapse of Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis — caused not by a formal flaw but by the inability to predict the real behaviors of its inhabitants within an overly rigid scheme — to modernist neighborhoods built with segregated pedestrian paths, which on paper promised order and safety but in practice produced deserted, barely accessible spaces. And again to the many European squares designed as large continuous surfaces, which, as temperatures rose, turned into heat islands because no one had imagined how materials, shading and microclimate would interact.

Obviously, a world model is not enough to eliminate the risk of error; it can, however, anticipate it in some cases, allowing designers to observe the behavior of a simulated environment and assess how an intervention would alter its balances, uses and reactions. It does not diminish the role of the designer — if anything, it reinforces the collaboration between human expertise and predictive capability. In this sense, the most significant transformation is the introduction of temporality as an integral part of the project: no longer a secondary effect, but a parameter that helps shape it from the outset.

The goal is not to let the machine take control, but to give the user real creative leeway

The Marble case

Leading the most talked-about shift of the moment is Fei-Fei Li, Professor of Computer Science at Stanford and a key figure in the field of computer vision, who two weeks ago launched the first commercial world model, Marble, through her startup World Labs.

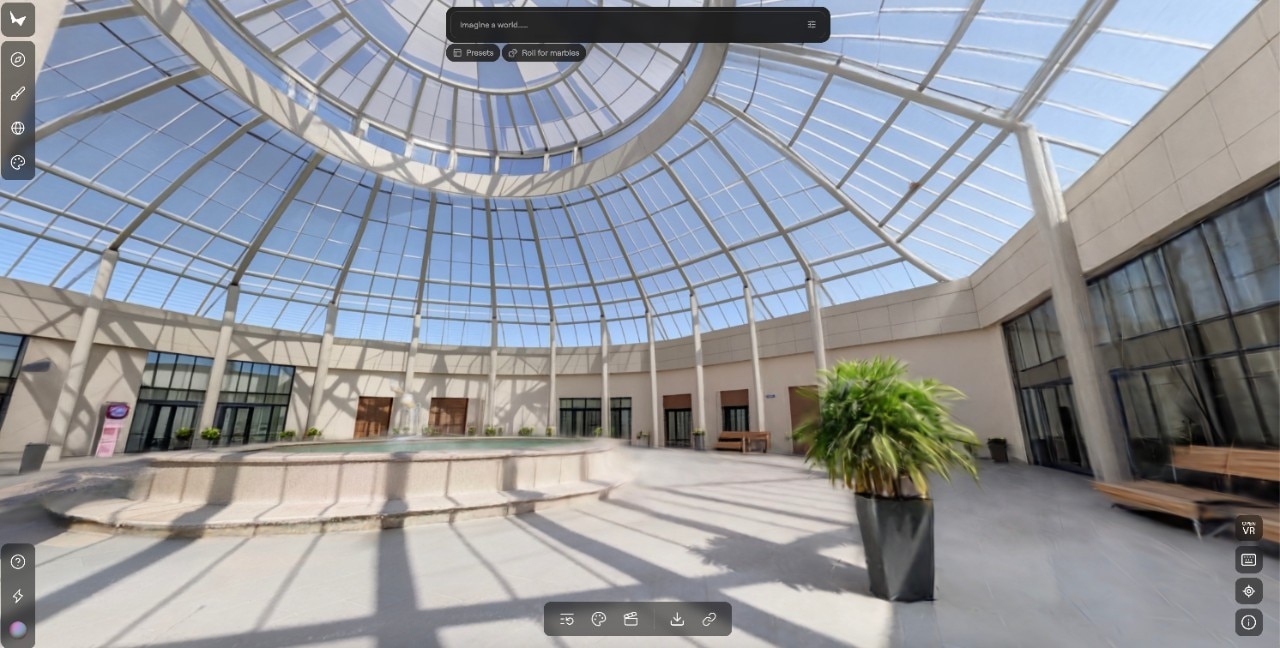

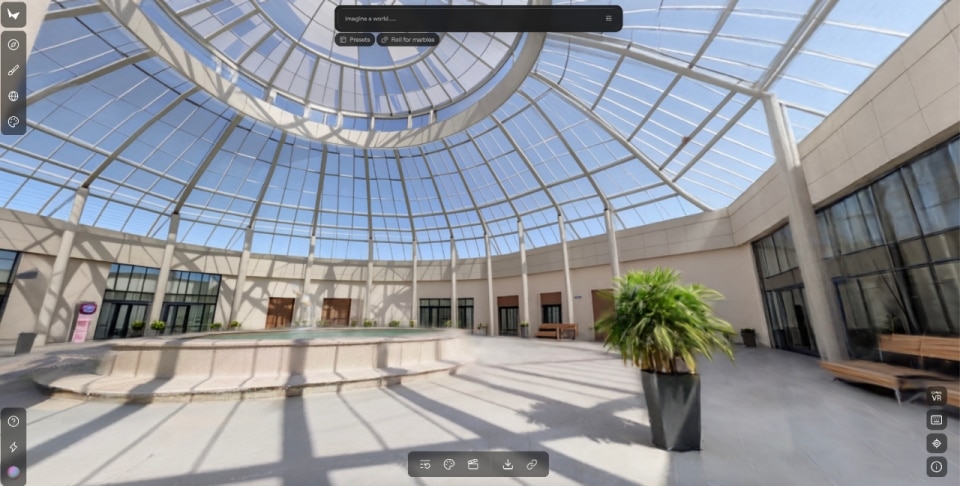

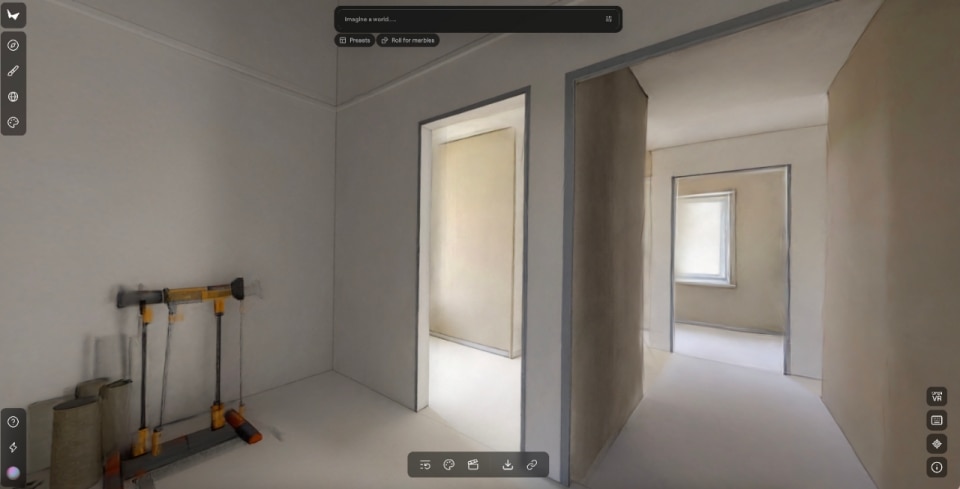

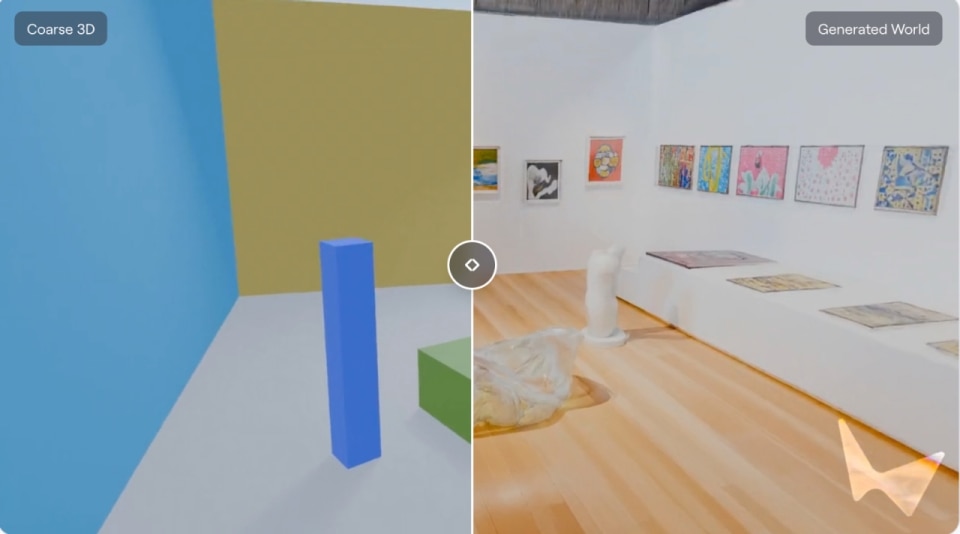

As Rebecca Bellan reports in TechCrunch, Marble generates persistent, editable 3D environments from text, images, video, or spatial layouts. Not worlds that warp as you move through them, but stable, coherent spaces that can be exported in professional formats and integrated into real pipelines such as gaming, VFX and VR. One of its most significant features is the ability to expand an environment or modify its structure through built-in editing tools.

Co-founder Justin Johnson emphasizes that the goal is not to let the machine take over, but to give users a real, immediate and direct creative edge.

Marble is only the first attempt to bring world models out of research labs and into production processes. And its applications extend well beyond functional disciplines: in the visual arts, it opens up new scenarios, from installations that react to audiences to immersive environments that evolve according to simulated logics, all the way to works that do not represent a world but activate one.