Finding one’s own dimension within a work environment can be a matter of escape, of finding one's freedom. Would we expect such a statement from Kengo Kuma? From the philosopher of harmony and contextuality, who has explored the mystique of craft and nature, ranging from tea houses to office complexes? The answer should be yes, and for the very reasons that have just been stated. Especially after these elements – within a professional practice as reflexive and critical as Kuma's – have kept reacting with the changes that the pandemic has made people clamor for, but which do not seem to have been taken up much , at a global level. At least, not by many.

Kuma, who in a 40-year career has designed the postmodern masses of the M2 in Setagaya-ku as well as the utmost contemporary expressions of traditional woodworking in the GC Prostho Museum Research Center and the Yusuhara museum-bridge, and sculptural expressions with strong landscape value such as the V&A Dundee, has instead openly embraced the idea of change in his vision – the idea of a constant evolution, to be more precise – especially in what concerns work, its role in human existences and the role of space in this relationship.

View gallery

View gallery

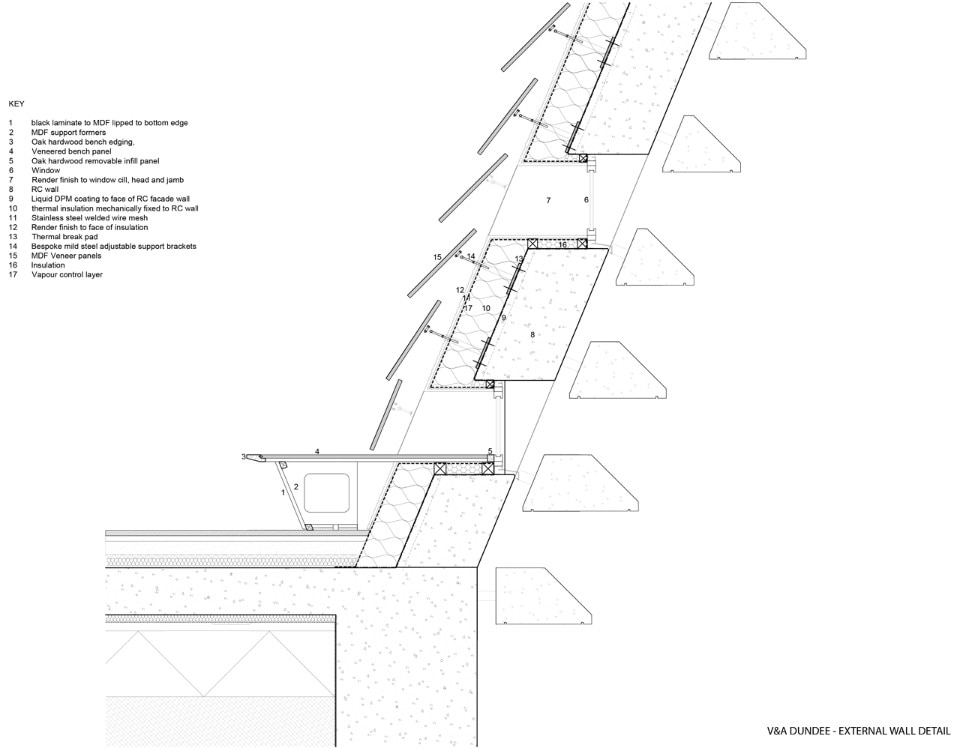

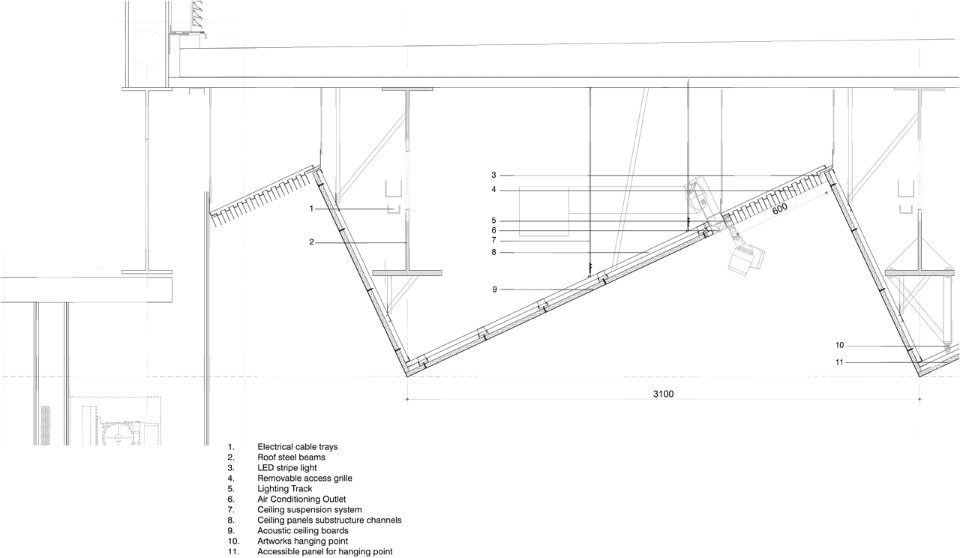

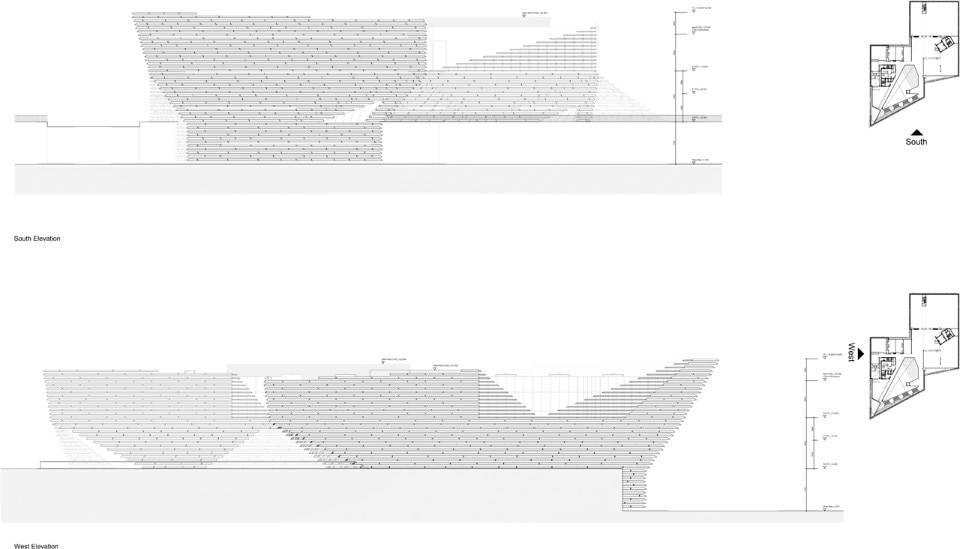

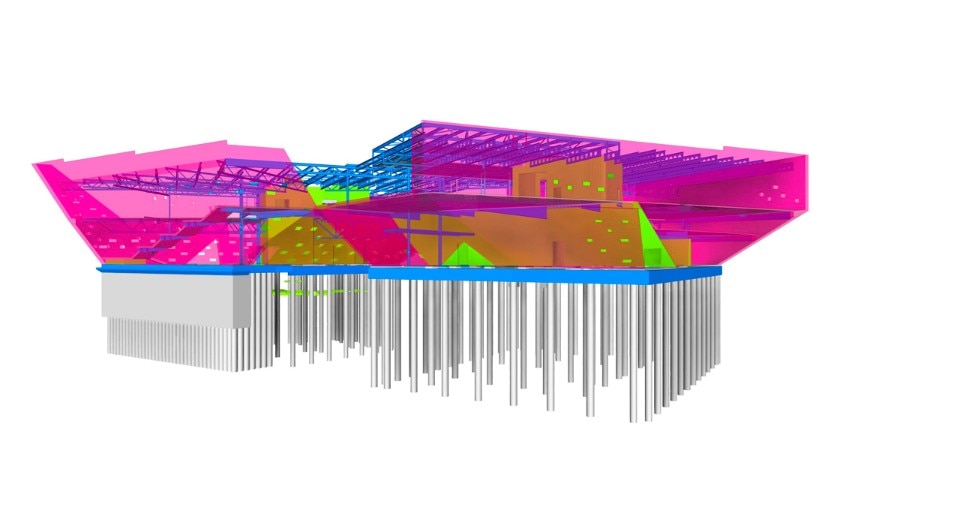

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

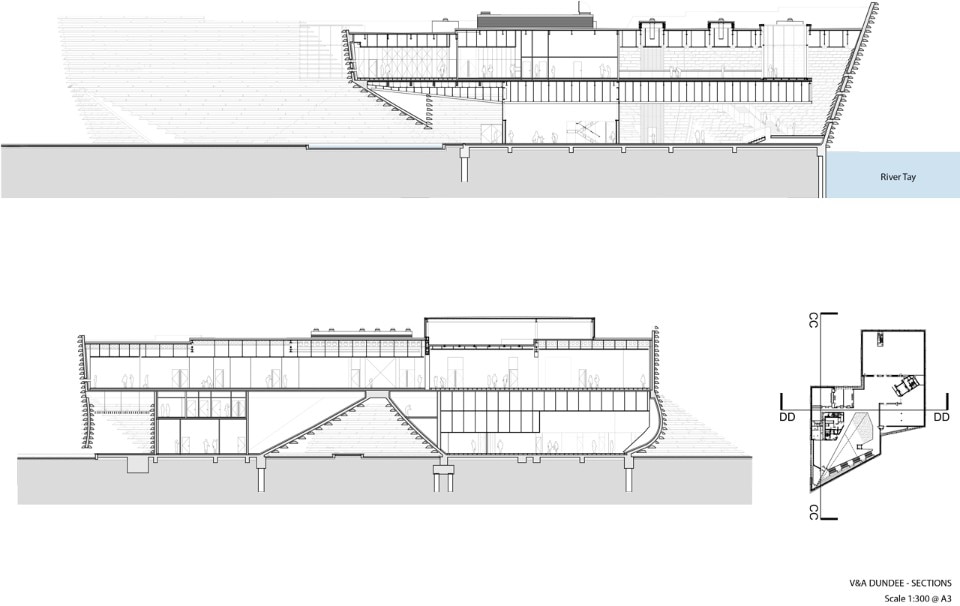

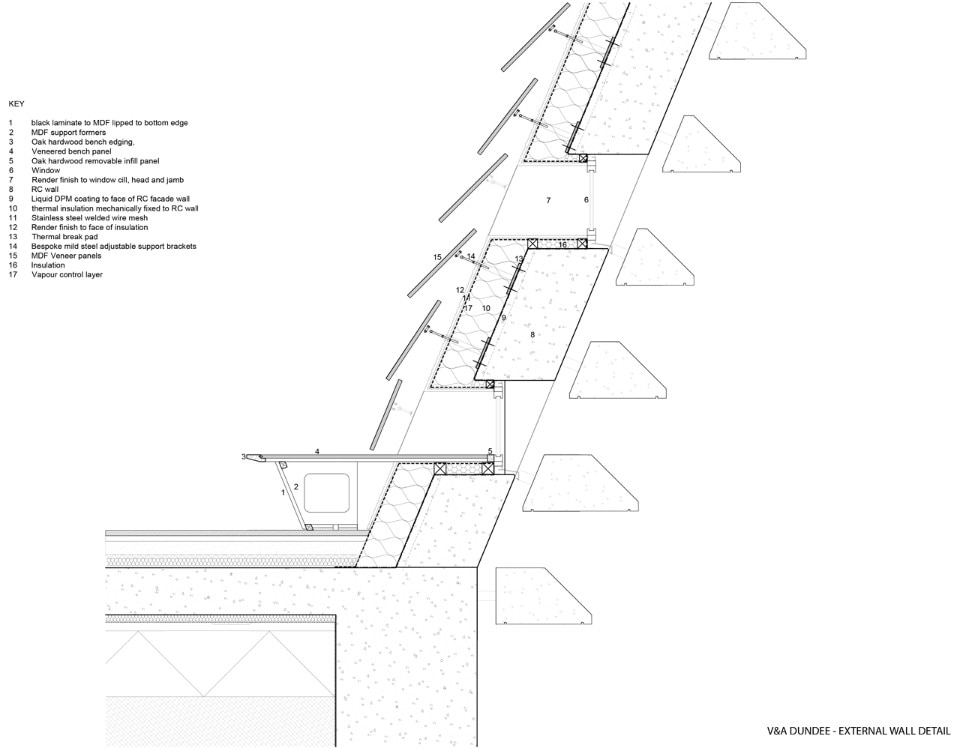

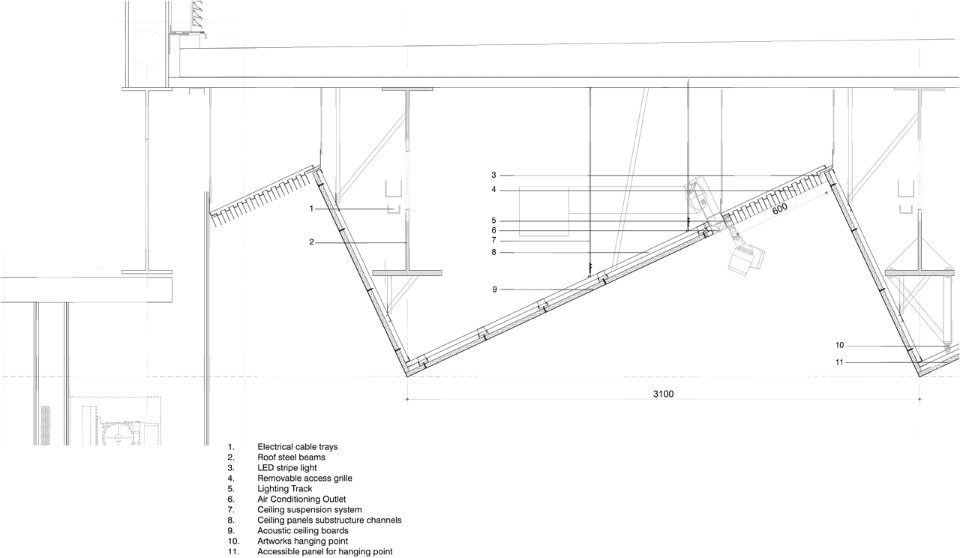

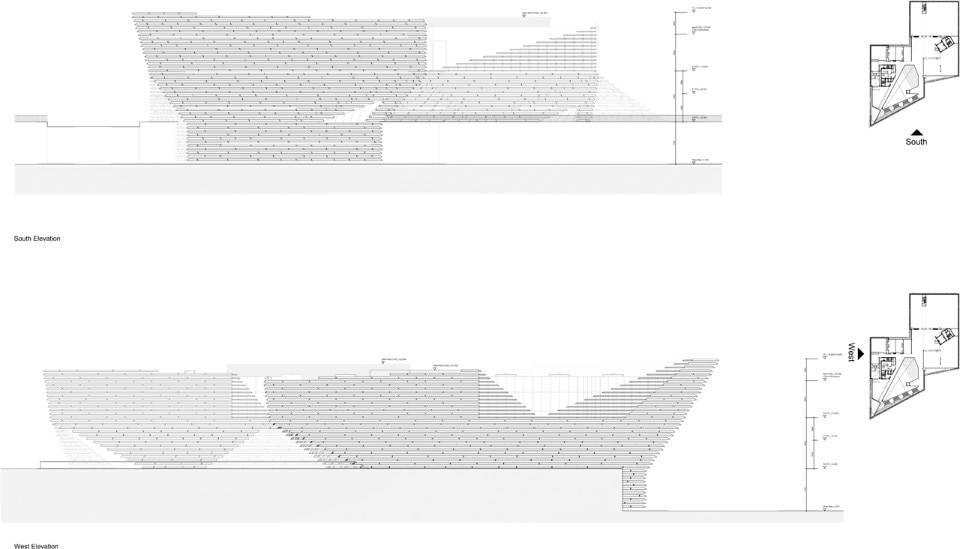

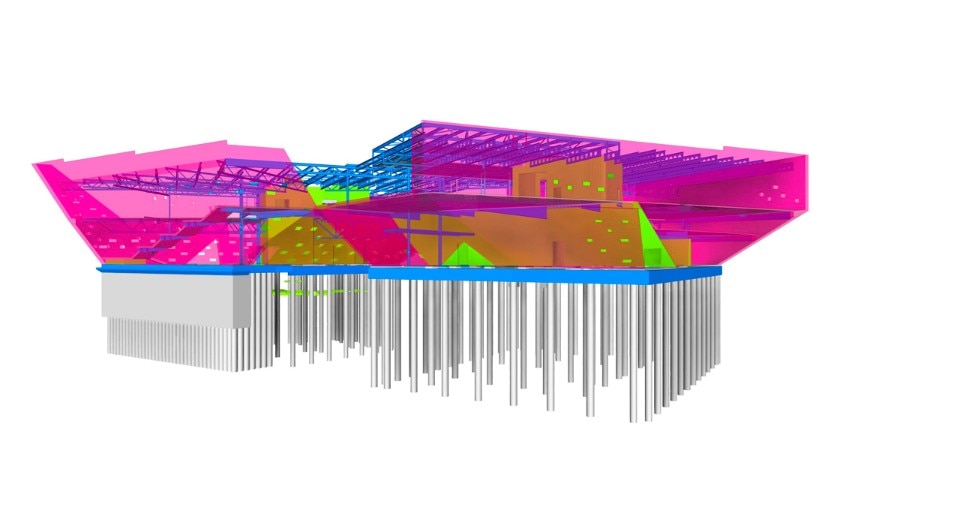

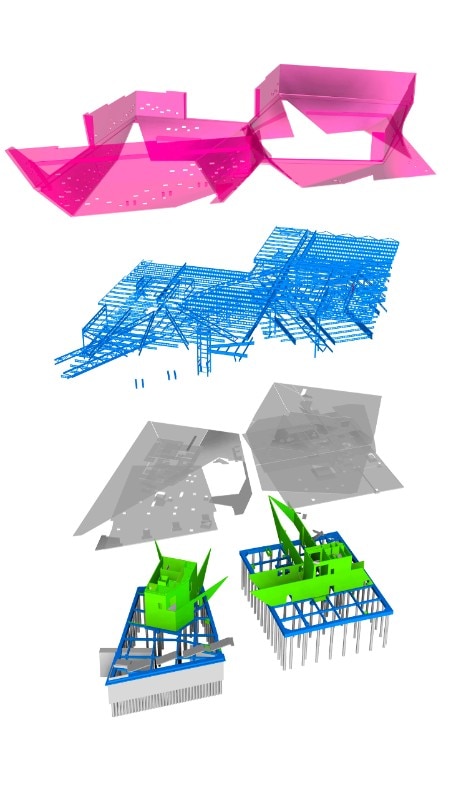

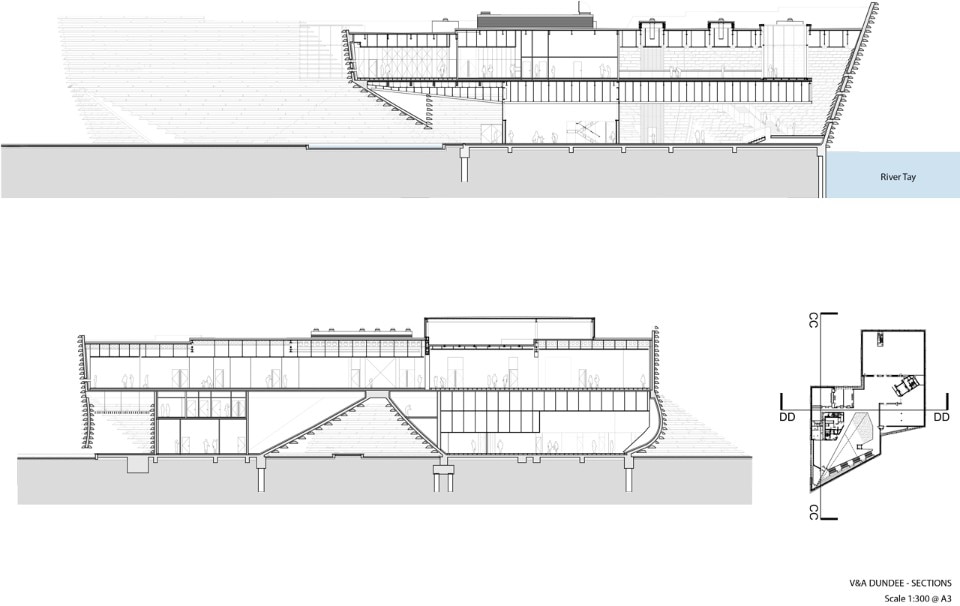

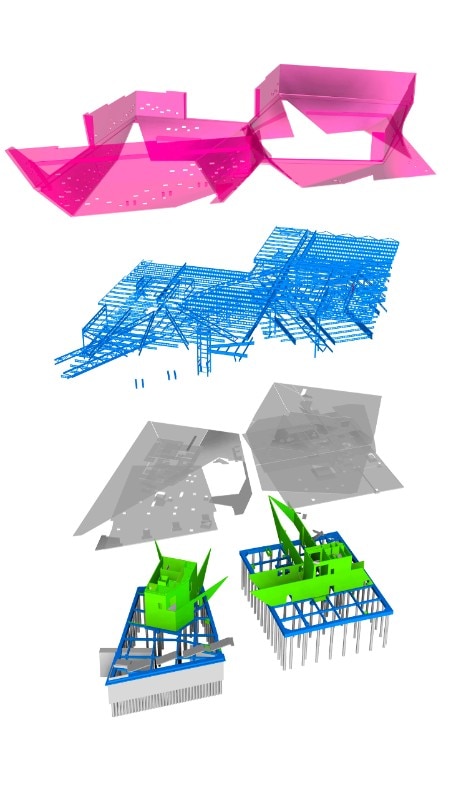

Kengo Kuma and Associates, V&A Dundee, Dundee (Scotland), 2018

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

Kengo Kuma and Associates, V&A Dundee, Dundee (Scotland), 2018

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

The Japanese architect is actually seeking for an improvement of workspaces through design, a much-needed evolution as he says: “By the beginning of the 20th century, workspace could be seen as a concrete high-rise building: it was efficient by then, with no mobile or pc, only landline telephones requiring enclosed space. Nowadays the environment is completely different but people has kept sticking to the high-rise model, which is a totally stupid behaviour now that we are in need of a working space shaped around new information technology”.

Information technology as well should be regarded as a multifaceted environment: both a tool to redefine proximity and a yoke we increasingly need to escape. Still, for the first reason it might provide the solution to the very issues it could cause. “Thanks to information technology we can now work surrounded by a comfortable nature, by a comfortable workspace: it is appropriate for workspaces, no longer forcing people to work all together in small spaces. Still, architects are not working for that kind of evolution, and it’s a big mistake: we should show this new kind of workspace to people”.

View gallery

View gallery

Kengo Kuma and Associates is by the way working in these months on the Welcome project, the renovation of the former Rizzoli facilities, east of Milan, together with Italian botanist Stefano Mancuso, which is announced as a combination of a biophilic approach, integrating natural life and work life, with a spatial tool that might sound more familiar, i.e., the free-plan open space layout. And this is the point where Kuma articulates in detail his position about workspace and the role of technology: “It’s just a first step” he says, “and I want to take a second, a third and so on. I think the important thing is that people can choose their workplace, we should have the perfect freedom to choose our style of working: some people want to work in a very enclosed small space, like a Japanese tea house, some want to work in a park, in the forest, in the mountains. Any location is possible for us; still, companies push people to gather in limited spaces: a very bad attitude, a system of control where we are kept as some kind of a convenience, a system we should escape, going beyond.

This is where the double nature of connectivity shows, and where the most radical steps should be taken, according to Kuma: “The risk about being connected is being controlled by the internet itself. My strategy to escape this kind of system is sometimes to cut the connection – to cut myself off the net. If I want to concentrate, I escape from the city: I have a small hut in the forest where I spend time thinking, writing, sketching... Everybody needs that kind of escape space in nature: it can give us that freedom we need to think.

View gallery

View gallery

KuMo Office. Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan.

Image courtesy of Kuma Mobile Office/Kengo Kuma and Associates.

KuMo Office. Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan.

Image courtesy of Kuma Mobile Office/Kengo Kuma and Associates.

KuMo Office. Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan.

Image courtesy of Kuma Mobile Office/Kengo Kuma and Associates.

KuMo Office. Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan.

Image courtesy of Kuma Mobile Office/Kengo Kuma and Associates.

KuMo Office. Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan.

Image courtesy of Kuma Mobile Office/Kengo Kuma and Associates.

KuMo Office. Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan.

Image courtesy of Kuma Mobile Office/Kengo Kuma and Associates.

KuMo Office. Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan.

Image courtesy of Kuma Mobile Office/Kengo Kuma and Associates.

KuMo Office. Higashikawa, Hokkaido, Japan.

Image courtesy of Kuma Mobile Office/Kengo Kuma and Associates.

It has a lot to do with Kuma’s personal approach to design as a practice, which he experimented since the early 90s when he first moved his studio activity out of the city to get in connection with local knowledge and craftsmanship. The pandemic, this time, has been a turning point in the evolution of such reflection: “In the Covid time I actually changed my working style. As a result of not going to my office I began to walk in my neighborhood, and I found many comfortable spaces: small parks, hidden benches, some secret restaurants... I’ve been walking around those spaces, and working. A new lifestyle was set, and finally I could get freedom from working and, it has to be recognized, all that was originated to Covid.

Now, as I could not be back to the office, we studied some small satellites in the countryside, and it gave us all new inspiration. There are still offices in Tokyo, Paris, Beijing and Shanghai, but we have these small spaces in Hokkaido, and Okinawa Island. I am working around these offices, and it gives an all-new stimulation to my brain”.

View gallery

View gallery

Opening image: courtesy Europa Risorse