“I’m always intrigued by this whole notion of time and how it relates to architecture”, says Marina Tabassum, the Bangladeshi architect who has designed with her studio a special Serpentine Pavilion: hers is the twenty-fifth episode in a series that has captivated the global architecture world, functioning as a prestigious annual award and, at the same time, as some kind of a real-time textbook on the third-millennium architectural history.

The Serpentine Pavilion is a temporary architecture project commissioned each year by the Serpentine Gallery (now Serpentine South) in London. Since 2000, a temporary pavilion has been built each summer in Kensington Gardens, near the Serpentine, designed by an internationally renowned architect who has never built in the United Kingdom before.

The “Capsule in Time” designed by Tabassum for 2025, with its wooden arches and translucent polycarbonate infill panels, is never really closed: its space is crossed by views of the park, it is aligned with the Gallery, and this axis also has a tree at its centre. It is part of the flow of the park and the history that runs through it.

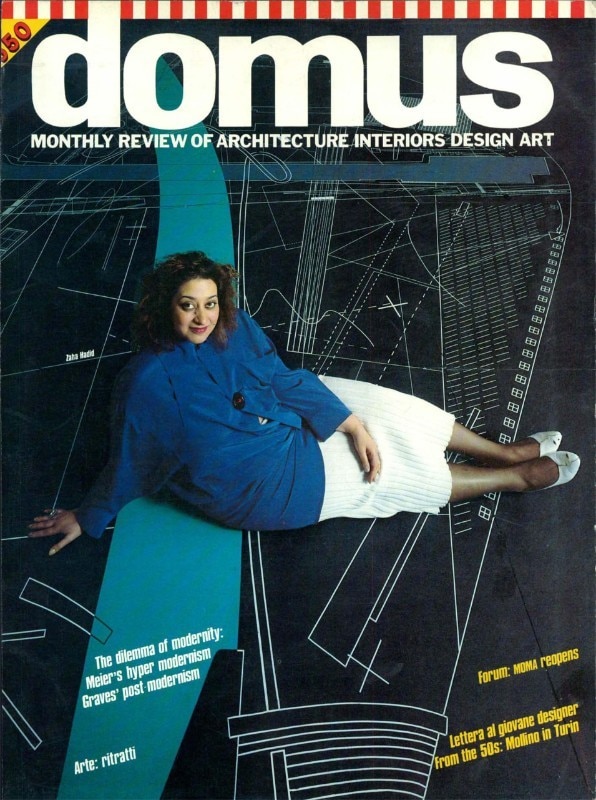

It is surprising, almost in a sense of a circle closing, to stop for a moment and think that the first Serpentine Pavilion, in 2000, was not only also designed by a woman architect, Zaha Hadid, but above all had a spirit extremely similar to that of Tabassum: it was created for the Gallery's 30th anniversary fundraising dinner and was based on the idea of a marquee, an event tent. Of course, form is very different, but those were the early-millennium years, the era of of star-architects as well as of an enthusiasm relying exactly on form that is difficult to replicate today.

In Bangladesh, we also have this temporality in our land, because the land is constantly moving, because it’s a delta, and people constantly move their houses, also from one place to another.

Marina Tabassum

In 25 years, the Serpentine has been a collector of architectural visions that we see confrontin each other – and sometimes clashing – in the present day all over the world. There have been a few exceptions, such as Oscar Niemeyer who, at the ripe age of 97, brought a small gem of tropical Modern to Hyde Park in 2003, capable of showcasing all its timelessness.

First, some pavilions were born as gestures, attractors and conveyors of attention (“it has become unmissable”, as the Financial Times said back in 2005, the year of Álvaro Siza) and experiences, the “open walls” to be explored, such as those by BIG (2016) and Frida Escobedo (2018), the enigmatic meditative cylinder by Theaster Gates (2023), or in particular the abstract, two-dimensional body of water with by Herzog & De Meuron, together with Ai Weiwei, which in 2012 took the public below the level of the lawn, doing a first work of “archaeology of the present” with the traces of previous pavilions.

There were also projects that interacted with the environment, be it the park landscape or a rapidly evolving macro-object: Sanaa's ethereal leaf-like roof (2009), for example, which blended in with the vegetation and sky; or even a device that was somewhere between technical and conceptual, still totally environment-based – weather-based, if you like, even more British – such as Rem Koolhaas’ 2006 pavilion, with its luminous balloon that ascending or descending, depending on weather and needs, to uncover or cover the meeting space below.

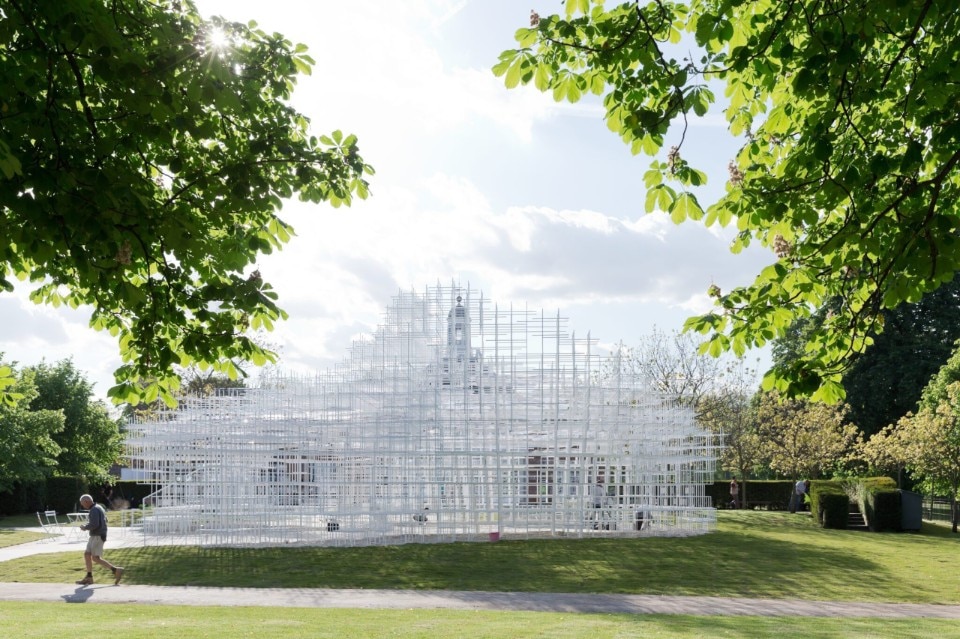

What has come to the fore in the last decade, however, is the Pavilion’s vocation as a place, rather than as a gesture or a marvellous machine: a collective dimension based on making things happen, or rather letting them happen better, within and through a space that, rather than being modified, is made “more visible”, more charged with possibilities: Sou Fujimoto's 2013 grid-cloud is perhaps the best representation of this approach, an indeterminate and potentially unfinished matrix, interpretable and usable at will, generated more by encounters than by forms – like Constant's New Babylon – in a blurring of boundaries between artifice and nature.

But there are also more recent projects that celebrate this primacy of practices and encounters, such as Lina Ghotmeh’s for 2024, and Tabassum’s for the 25th anniversary. “Architecture has always sought out permanence and timelessness, how you can continue beyond your existence”, Tabassum told us, but in her pavilion it is precisely the idea of “timelessness” that changes definition. There is nothing static about it anymore; it is built entirely on the ability of architecture to take on content, practices, uses, and to carry with it that almost intangible heritage, even when moved elsewhere.“Serpentine Pavilions actually are then sent to somewhere, acquired by somebody, find a new way of use. And in this case (the 2025 Pavilion, ed.), I hope someone acquires it and turns it into a library”. That's why wood and polycarbonate have been chosen, so that it can be reused many times and for longer. “So that it is ready for shipping, absolutely”, totally, entirely. “Except for the floor”.

Tabassum's “Capsule in Time” opens on 6 June in Kensington Gardens, London.

Opening image: Serpentine Pavilion 2000, designed by Zaha Hadid. © 2000 Hélène Binet