“My father was a sailor who worked in the whaling industry. My mother's Canadian but she was born in Scotland and, after marrying, came back to work in one of the many jute mills. I married an Indian Sikh. We're local and global. That's Dundee. Have you seen the museum yet?” Talking to taxi drivers is a great way to feel the pulse of a city and that certainly goes for those in the Scottish city of Dundee, where the first Victoria & Albert Museum outside London opened on 15 September.

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. It was later named after Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert, who had championed it.

Can an iconic institution devoted to creative enterprise revive the fate of a major city seriously harmed by unemployment and the post-industrial recession? Can a Scottish design collection project its rich identity and heritage globally? Will it attract visitors to discover or rediscover the genius of Christopher Dresser and Charles Rennie Mackintosh, the history of tartan and Hunter boots, the carpentry of the shipbuilding industry and DC Thomson's comic book world? How do you tell the story of a city built on trade and immigration in the Brexit was using objects?

View gallery

View gallery

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

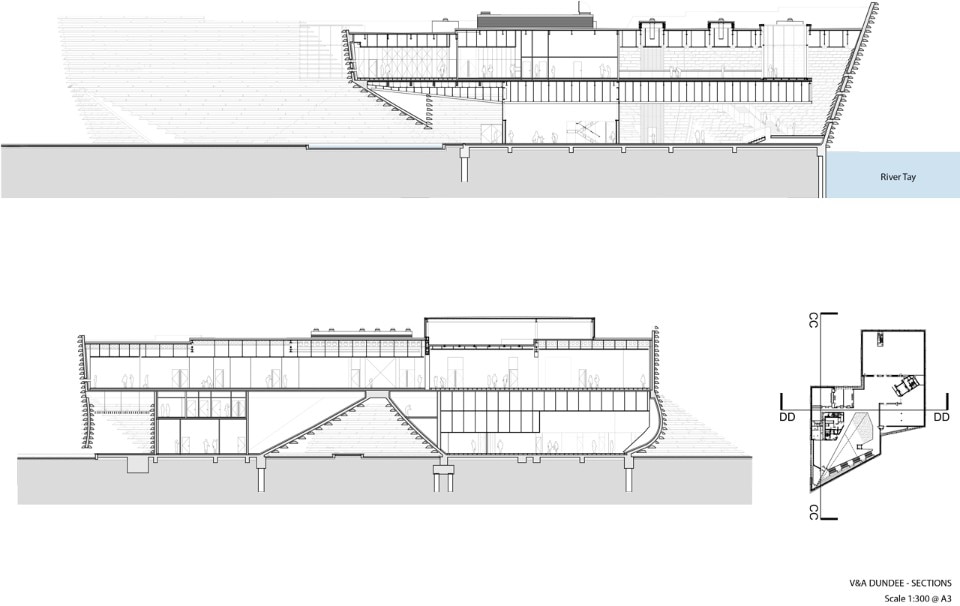

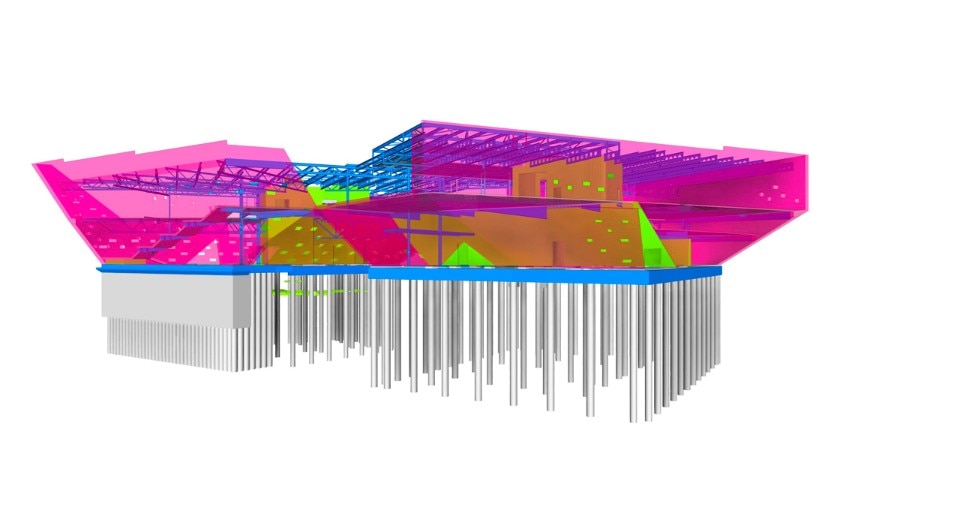

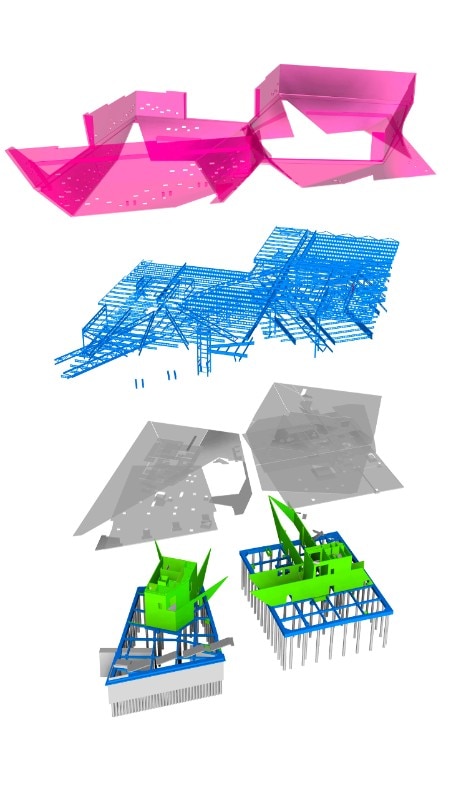

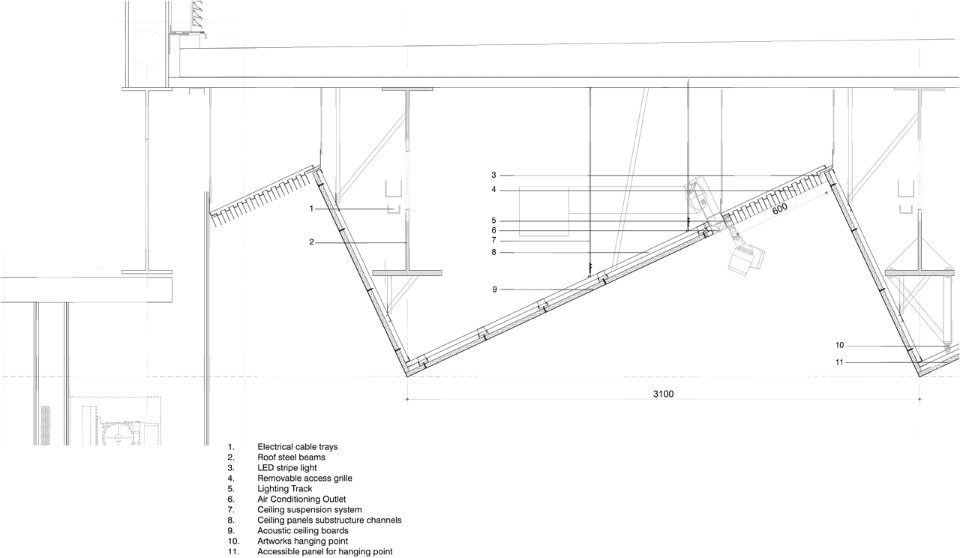

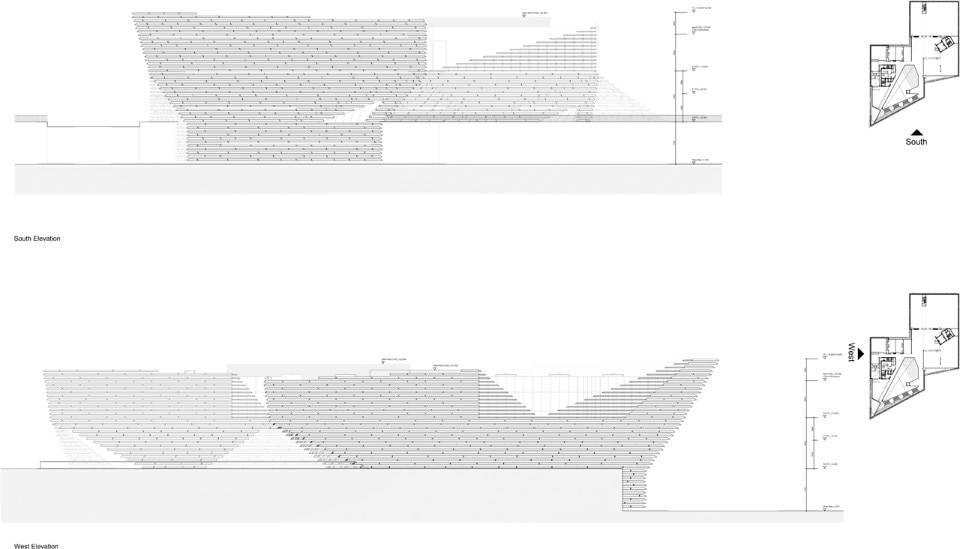

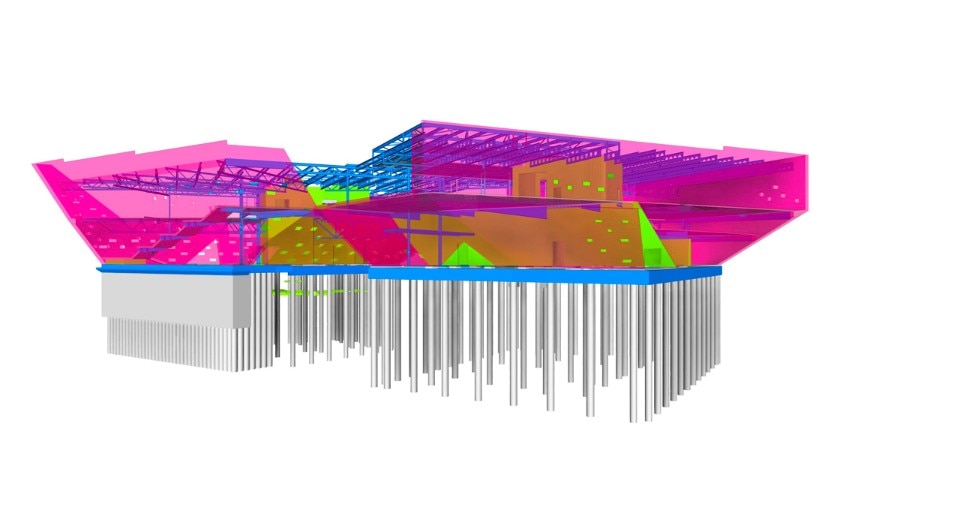

Kengo Kuma and Associates, V&A Dundee, Dundee (Scotland), 2018

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

Kengo Kuma and Associates, V&A Dundee, Dundee (Scotland), 2018

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

V&A Dundee, 2018

The V&A Dundee is the new offshoot of the world's leading design institution, founded in South Kensington in 1852 by tenacious designer and businessman Henry Cole. The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications, writes Paola Nicolin.

The opening of this design museum directed by Philip Long has inevitable social and political implications. All the museum's communication and projects, including its central Learning Center, have a strong policy of involving the community and schools - in keeping with the conviction that art must underpin an education, firmly rooted in the country by the art historian Herbert Read. The mind goes naturally to the Tate, Pompidou and, albeit differently, the Guggenheim. All have opened operations far away from their parent institutions but perhaps here, together with the stress on placing education at the heart of all the new institutions, the choice of Kengo Kuma rooted the focus more strongly on the setting. His architecture expresses concepts simply and authentically.

The museum will form the bridgehead of a redevelopment of the city's waterfront, a one-billion-pound investment, 80 million of which allocated to the museum project. Dundee is starting again from the water. it was a city of trade, of arrivals and departures, celebrated by the Royal Arch, symbolic architecture built in 1844 to honor Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, the sovereigns who gave the original museum its name, on their first visit to the Highlands. The arch was demolished in 1964 to build the Tay Bridge, connecting industrial Dundee to the golf courses of St Andrews just over the hill. Deprived of its maritime functions, the waterfront first became an inactive threshold and then a dirty pavement.

The city begins anew from here with the famous museum as its beawith although it has already been building new hotels and spaces for domestic and international visitors in recent years. The aim is to put Dundee on the entertainment economy and creative culture map. Dundee's culture nous also has solid roots in its major scientific and university pole, the University of Dundee and Abertay University, partners in the museum with the City Council and Scottish Enterprise.

It was named UNESCO City of Design in 2014, the local area is home to 10% of the videogame industry and there are prestigious schools of visual arts where internationally renowned artists have trained. Not the least of its merits has been its success since 2008 in attracting considerable amounts of funding from local and international trusts, backed by the project's major founders: the Scottish government, the UK and the Nationat the Lottery. If Cole saw the V&A as a schoolroom, the idea of a museum as a bridgehead in the rebirth of a university city is not such a bad idea. More than ten years have passed from the first discussions to its opening, and three directors of London's V&A have come and gone in that time (Mark Jones, Martin Roth and current director Tristram Hunt) whereas only one civil servant in Dundee has been involved in the project: Mike Galloway, Executive Director of Dundee's City Development.

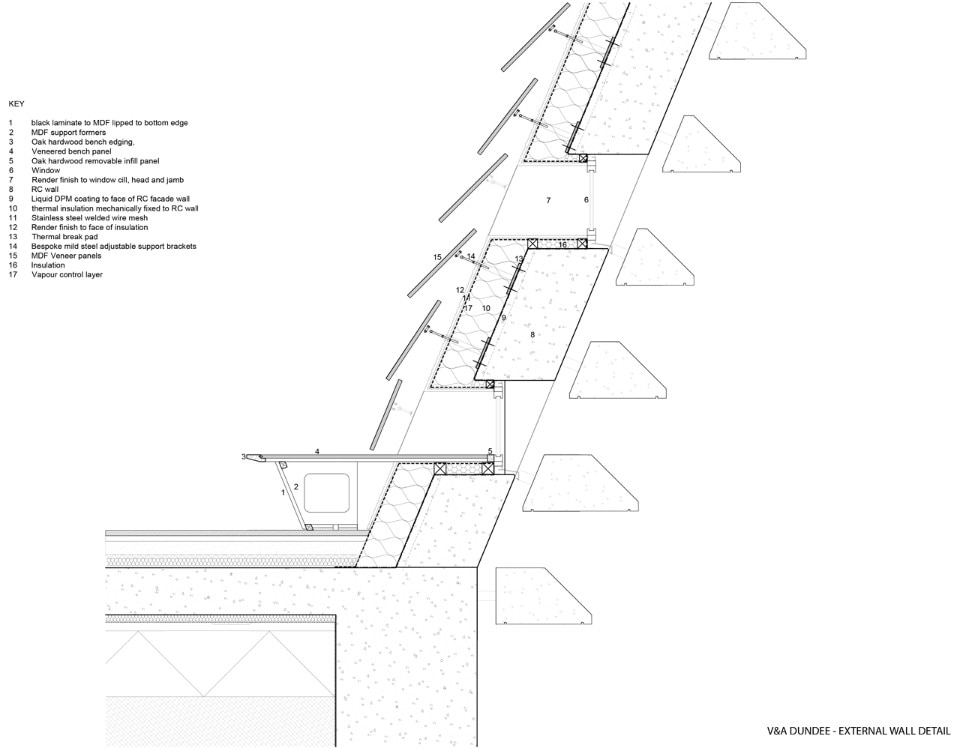

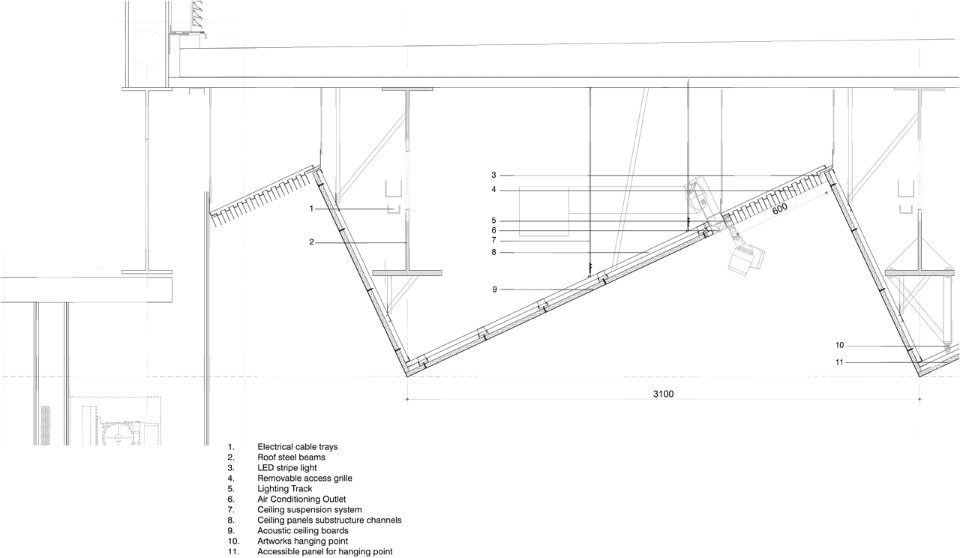

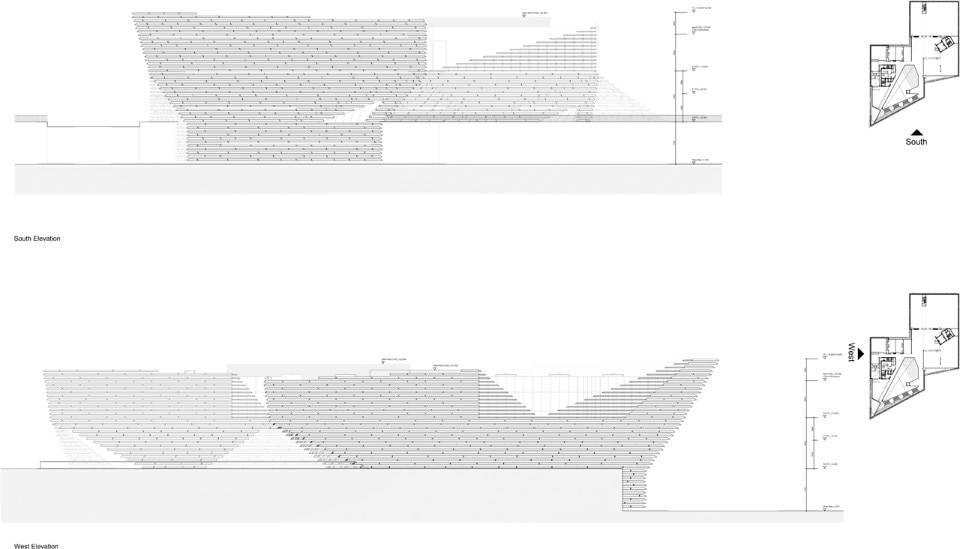

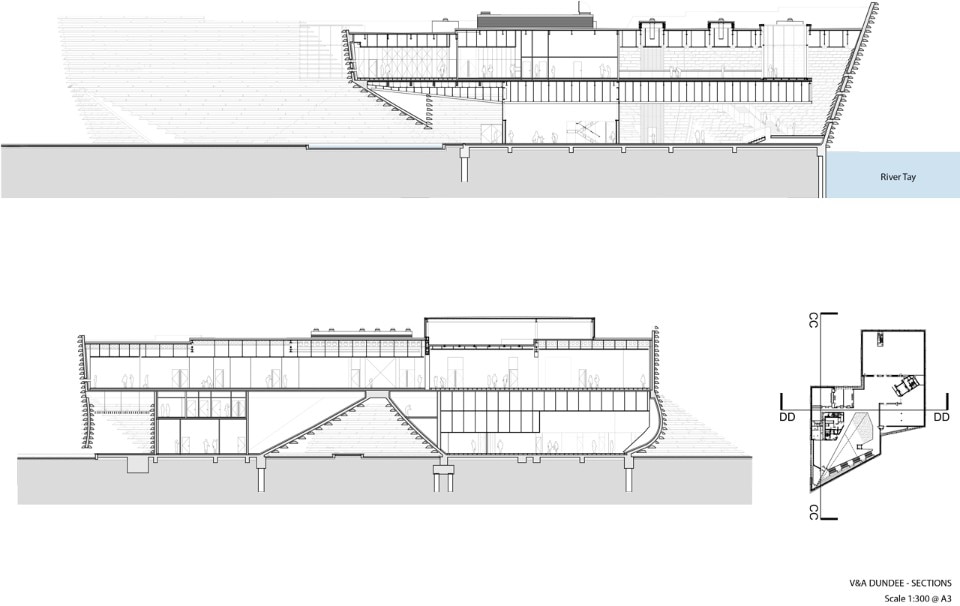

The institutional reins of this operation were, however, in the hands of a woman, Moira Gemmil, formerly Head of Design at the South Kensington Museum. A graduate of the famed Glasgow School of Art, she left the Museum to run the Royal Collection Trust but, in 2015, was knocked down and killed by a lorry in the centre of London while cycling to her office. All the designers involved, from Kengo Kuma to his assistants, London-based office ZMMA, which designed the interiors of the Scottish Galleries, and Cartlidge Levene, which produced the graphic design for the museum's wayfinding, pay tribute to her tenacity and vision, a professional who saw the museum as an institution to be continually rethought and custom designed, room by room. Kengo Kuma has designed a very flexible but welcoming space. This is his first building in the UK and he and project architect Maurizio Mucciola, who oversaw the build, insist that the 2010 proposal won over the jury of the international competition with the concept of a place that would bring the city together, give back a meaning to its waterfront and renew the relationship between city and sea. Today, Kengo Kuma presents the project talking of flows and nature, of with concern for people's moving bodies, forms, materials and construction techniques inspired by the Scottish cliffs.

Asked “Why put the stress on the body?” Kengo Kuma replied “Do you know the Metabolism movement? Ever since that period in architecture I have not cared so much about the structure as the flow of people in space. ” His first sketch had already defined the form of the architecture overlooking the river, sinuous and with a large void at the center, tying together with the main city axes along Union Street and Discovery Point. it consists of two inverted pyramids, seemingly separated on the ground floor and rotating to join up again on the first floor.

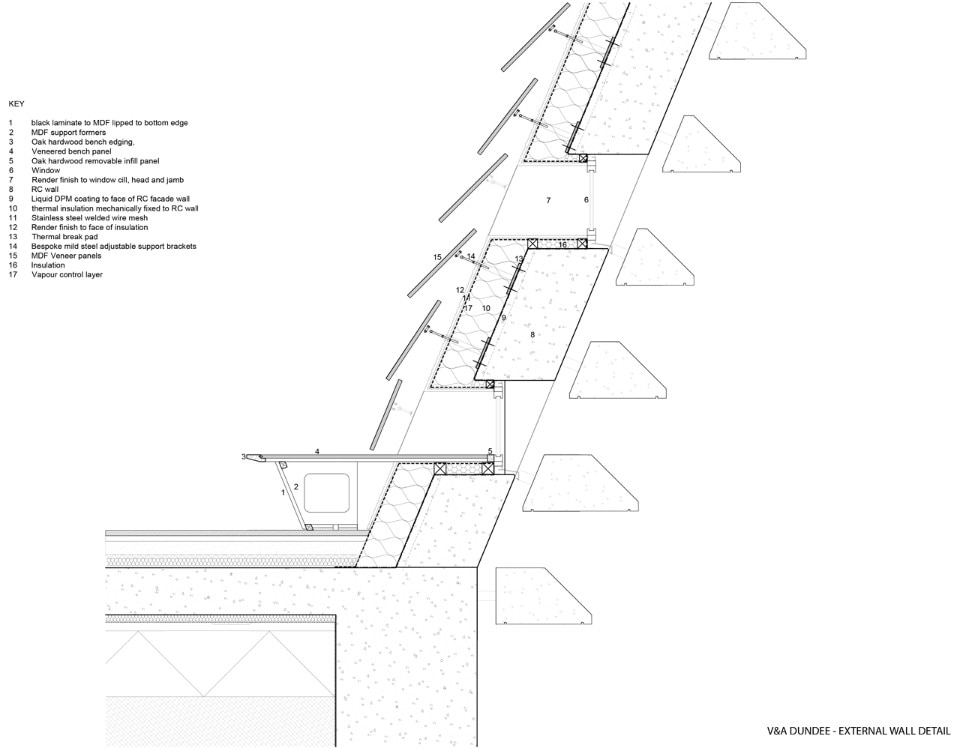

The museum not only overlooks the water but incorporated it with its foundations in the riverbed. The exterior is an organic layering of bedded stone running around a curved reinforced-concrete wall. “In Dundee four seasons pass in four hours. The construction system works with shade, light and wind, and we sought to create sightlines uniting exterior and interior, ”explains Mucciola. Stone outside and timber inside. The alternation embodies the traditional construction of Scottish houses, of the kind that can be seen across the river in the village of Newport to which the wealthy inhabitants of Dundee moved to get away from the stench of industry on the other side of the river.

This article was originally published in the Domus October 2018 issue.