Thinking about wayfinding as an action, rather than a discipline, is probably the only way to fully understand its value and critical role in shaping the user’s experience of a space, believes a new school of thought of experts.

Usually defined as the process of ascertaining one’s position in an environment, planning a recommended route and offering the tools to follow it, wayfinding has massively changed over the years.

“You can’t design wayfinding, you do wayfinding,” asserts Dr Colette Jeffrey, Associate Professor of Wayfinding and Inclusive Design at Birmingham City University. In her opinion, taking an academic point of view on the topic is really just about answering the key question: “What is that we do as navigators?”

It all starts with understanding that people find their way differently, depending not only on the place but also on their physical and psychological conditions during the journey, Jeffrey explains. “Imagine if you’re moving in a hospital thinking you’re going to die of cancer versus if you just had a baby.”

Therefore, a big responsibility of architects and designers alike is to not make assumptions about built environment navigation simply based on their personal experience and shift the focus on inclusiveness and accessibility.

“A well-functioning wayfinding system has to be multisensory, both visual and audible, to have a completely and totally inclusive system,” Jeffrey adds. “But it’s very tricky and very few places do it well.”

And while buildings accessibility has massively improved (specifically in the UK after the Disability Discrimination Act in 1995), inclusive design is often not in-built during the construction phase. “Generally we are just brought in when there’s a problem,” the professor remarks.

Compromising with design and architecture

Another intention as well as a challenge of contemporary wayfinding is to be harmonious and coherent within a space. A master example of that is the signage project for London’s new Design District which accurately used graphics, colours, shapes and materials to reflect and celebrate the eclectic nature of the district.

According to design studio DNCO, a London authority in wayfinding systems, “understanding the multiple cues people are following,” which go well beyond signage, becomes crucial to creating that harmony.

“People follow architecture, light, sounds and smell when they move; the environment is actually directing them through a space a great deal more than pure wayfinding,” Patrick Eley, Creative Director at the studio, tells Domus.

Based on those considerations, the wayfinding expert should design a navigation unique code for each specific space and develop the tools to help people learn that code quickly when they arrive at the site.

“But you always have to remember that you are dealing with lots of different people, ages and languages,” Eley adds. “So the notions of being clear, coherent and consistent with that code become very important.”

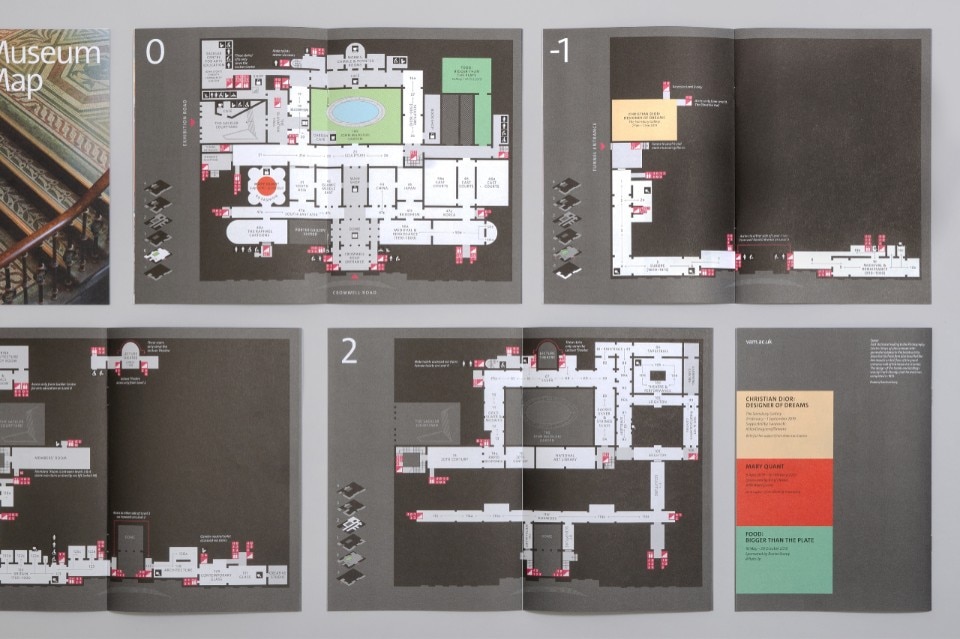

DNCO has recently been working on an important wayfinding project for the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. One of the main takeaways from the job was that signs always need to be sensitive to the environment.

“Particularly with museums and galleries, you’ve got to think artistically and architecturally, being very conscious of where you’re putting a sign,” Eley explains. “Hanging something next to an artwork on the walls of a museum is a huge responsibility. But it’s also great because you’re working with people who really understand the power of design and the language of objects.”

People follow architecture, light, sounds and smell when they move; the environment is actually directing them through a space a great deal more than pure wayfinding

He stresses the importance of refraining from way finding’s temptation to ‘coach’ rather than ‘support’. “You don’t want to out art the art that people are coming to see. You are just helping them to find the way.”

For this reason, the studio opted for a quiet approach, completely removing colour from the signage at the V&A museum. “We also didn’t want to overwhelm people with information. Being clear is about giving them the information they need at the point that they need it to make a decision,” he adds.

But that is also dependent on the very architectural nature of the space, to the point that the lines of when a sign becomes part of architecture and vice versa can blur. “Sometimes both wayfinding and architectural elements contribute to defining a location,” comments Eley. “The Hollywood sign in LA marks the name of a place, but also creates that place; similarly to how we would immediately associate the Shard with the city of London.”

The evolution of wayfinding: post-Covid wins and new challenges

Even when engaging with the design aspect, constant thinking for the wayfinding consultant remains on how to use inclusive language. Whether that means choosing words more mindfully (e.g. ‘No entrance’ vs ‘Staff only’) or using icons to overcome language barriers, the tone has to be welcoming for all.

A good example of the industry’s effort in this sense is that of creating more non-binary, un-gendered spaces. “The classic male/female icons that are used for denoting toilets is totally not where we are as a society,” Eley points out.

“Wayfinding has a huge amount of responsibility in deconstructing that.”

In his view, every space other than toilets uses icons to represent the function of that space, whereas public bathrooms tend to be identified by the icon of who they are for. That mainly happened for reasons linked to cultural taboos but, Eley says, the main question now becomes: “How can we create an icon for those spaces that makes them utterly inclusive?”

The designer agrees that Covid helped massively in moving the needle forward. “During the pandemic, people realised the importance of public spaces to aggregate and that segregating on the basis of gender ultimately is not inclusive. I believe the change has accelerated.”

And in times of rethinking the function of office spaces and buildings’ role in favouring health and wellness, wayfinding has also taken on flexibility as a priority.

“We learnt that the function of spaces can change, something important to consider when we design that signage code. Can wayfinding accommodate the changeable nature of a site? Like when the building is sold or things like Covid happen?” Eley asks.

But with the learnings came a whole new set of challenges too. Some of the emergency wayfinding systems adopted in public spaces during the pandemic were not inclusive at all. The floor signage to mark social distancing or queueing areas we are all too familiar with was not taking into account visually impaired people.

The increasing adoption of digital signage to avoid physical contact has also posed a new problem, related to the sustainability and energy consumption aspect of the buildings themselves.

So, what’s ahead for wayfinding? In Dr Colette Jeffrey’s opinion, the future of wayfinding will explore those inclusive design considerations from the very start. “A big part of solving these problems is mapping different journeys, so the more different users are taken into consideration, the better the system will be.”