This article was originally published on Domus 1040, November 2019

How shall we live in the future? More specifically, how can we hope to flourish on our crowded, overheating planet? Whatever the answers to such questions, one thing is for sure: the way we eat will be pivotal to our chances.

Living in a modern city, it can be hard to see quite how fundamentally food shapes our world. Industrialisation has obscured the vital connections without which urban life would swiftly grind to a halt: the complex supply chains that channel our food from the landscapes where it is grown to our supermarkets, cafes and kitchens. The meal on your plate is more than just nourishment: it is an emissary from another world – a place we still call “countryside”, yet one that rarely resembles the bucolic paradise of our imagination.

Most of our food these days is produced in streamlined, super-scaled facilities the reality of which can both amaze and shock. From vast sheds and feedlots full of tragic animals to monocultural grain-fields harvested by phalanxes of combines and robotised production lines churning out tins of baked beans, the spaces and processes that underpin our 24/7 existence are as mesmeric as they are ruthless.

In many ways, modern agri-food epitomises the fateful combination of technical prowess and blitheness that now threatens us and our planet. Our modern way of life is based on the illusion of cheap food. Yet when you consider that food consists of living things that we raise and kill in order to live, it is clear that no such thing could exist.

On the contrary, should the numerous “externalities” of industrial food – climate change, deforestation, mass extinction, pollution, water depletion, soil degradation, obesity and diet-related disease – be internalised, it would become instantly unaffordable. All of which raises the question: what would happen if we did precisely that?

The short answer is that there would be a revolution, not just in the way we eat, but in how we live. Cheap food forms the basis, not just of our food system, but of our existence. Our politics, economics, habits and values – our very idea of a good life – rest on the fallacy that we’ve solved the problem of how to eat.

The meal on your plate is more than just nourishment: it is an emissary from another world – a place we still call “countryside”, yet one that rarely resembles the bucolic paradise of our imagination

Any attempt to revalue food will thus be met with stiff resistance, not least among politicians. Yet such a move is arguably the single most powerful thing we could do in order to transition from our unhealthy, unsustainable, inequitable society towards a far better one. Whether or not we realise it, our bodies, homes, cities and landscapes are all shaped by food. We thus live what I call a sitopia (from Greek sitos, food + topos, place); just not a good one, since we don’t value the stuff from which it is made. Sitopia isn’t utopia – that, indeed, is its point – yet by learning to value food and harnessing its power, we can come close to the utopian dream of creating a fair, healthy, resilient society.

Food is a major theme in utopian thought because its vital importance was obvious to our ancestors. Feeding cities in the pre-industrial era was hard, not least due to the difficulty of transporting food so that it arrived in an edible state. For this reason, most cities remained small and were highly productive: surrounded by market gardens, orchards and vineyards and with many householders keeping pigs, chickens or goats, and doing their own baking, brewing and pickling. For Plato and Aristotle, such self-sufficiency was a key aim of the polis, or state.

Their ideal vision was based on oikonomia, or household management: the idea that each citizen should have a house in the city and a farm in the countryside from which to feed it. Scaled up, such an arrangement would render the state self-sufficient and thus politically independent. To achieve this, the polis should remain relatively small – an idea echoed both by Thomas More in his 1516 Utopia and by Ebenezer Howard in his 1902 Garden Cities of To-Morrow.

Today on our shrinking planet, such models are once again highly relevant, laying out the concepts necessary to create the sort of resilient, locally-based, steady-state economies we shall need in the future. Such models also suggest how the world might change were we to put the oikonomia back into economics. Long banished to the periphery of our lives and minds, food would be back at the centre of things.

Architects and planners would no longer dream of designing kitchen-less flats, allotment-free housing or unproductive cities. Instead, the race would be on to post-fit our homes and spaces with the stuff without which there is no life.

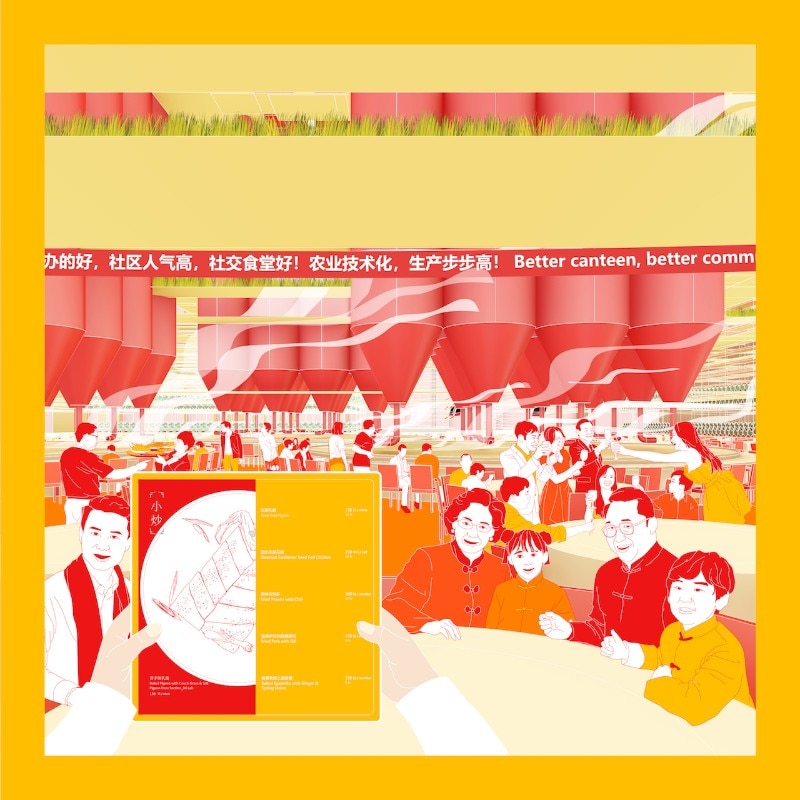

Flats and houses would revolve around kitchens, gardens, cooking, shared meals and community compost heaps, markets and highstreets would flourish, gardens and balconies would burst with home-grown produce, and networks of small producers and suppliers would reconnect cities with their local hinterlands.

Farmers would no longer work against nature, but with it; industrial feedlots and “Big Ag” would be replaced by smaller-scale, agro-ecological farms and rewilded land. Instead of being dehumanised and exploitative, food chains and businesses would become regenerative, crafts-based and artisanal.

If this all sounds somewhat utopian, it is: when food is valued, sitopia tends towards utopia. Yet such transformation is far from fantasy; on the contrary, it is already happening.

The Food Movement – an international assemblage of farmers, producers, groups and organisations such as Slow Food and Via Campesina (the global peasants’ movement), is built around the recognition, protection and production of food that is, in the words of Slow Food founder Carlo Petrini, “good, clean and fair”. In the industrialised world, projects including community gardens, CSAs (Community Supported Agriculture), box schemes and farmers’ markets have already demonstrated how valuing food can transform lives, economies and spaces.

Meanwhile in the Global South, awareness is growing of the need to protect indigenous food cultures and traditional agricultural practices before it’s too late.

While the Food Movement demonstrates the potential of bottom-up transformation, building a true sitopia will also require government intervention. Only governments have the power to strike the balance between city and country that is so essential to civilisation.

When food is valued, sitopia tends towards utopia. Yet such transformation is far from fantasy; on the contrary, it is already happening

When Ambrogio Lorenzetti painted his 1338 Allegory of the Effects of Good Government in Siena’s town hall – arguably the greatest representation of that key relationship – the title of his work was significant. Siena’s rulers knew, like Plato and Aristotle before them, that maintaining a balance between city and country was their primary responsibility.

The Greek polis and medieval Italian city-state are rare examples of when this principle was understood. Howard’s Garden City at Letchworth and Patrick Abercrombie’s 1944 London Green Belt followed their lead, using planning to limit urban growth and make, as Patrick Geddes once put it, “the field gain on the street, not merely the street gain on the field”.

Geddes proposed an alternative to the “green belt” concept by suggesting the preservation of strips of countryside radiating out from city-centres to create star-shaped metropolises where urban and rural would remain in close proximity. Tokyo’s 1952 Agricultural Land Act achieved something similar, preserving an unlikely patchwork of organic farms in the core of the megacity that still survive to feed their local communities.

Modern efforts to reconcile city and country include MVRDV’s Almere Oosterwald masterplan, which incorporates a mix of farms, factories and housing in a deliberately fluid design, and British-based architects Viljoen and Bohn’s concept of CPULs (Continuous Productive Urban Landscapes), which link underused urban spaces such as car parks and verges to create green corridors out into the countryside, echoing Geddes’ star-shaped vision.

No matter how it is achieved, the key to our future rests on valuing food, farming in harmony with nature and reconnecting city and country. By putting the oikonomia back into economics, we can build the sorts of liveable, resilient communities we shall need in order to thrive in the twenty-first century.

By letting food be our guide and respecting those who feed us with love, we can reset our idea of a good life and look forward to a flourishing sitopian future.

Carolyn Steel, London-based architect and lecturer, is a leading thinker on food and cities. Her 2008 book Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives (Vintage Publishing, 2013) has gained broad recognition. Her next book, Sitopia: How Food Can Save the World, is due be published by Chatto & Windus in March 2020.