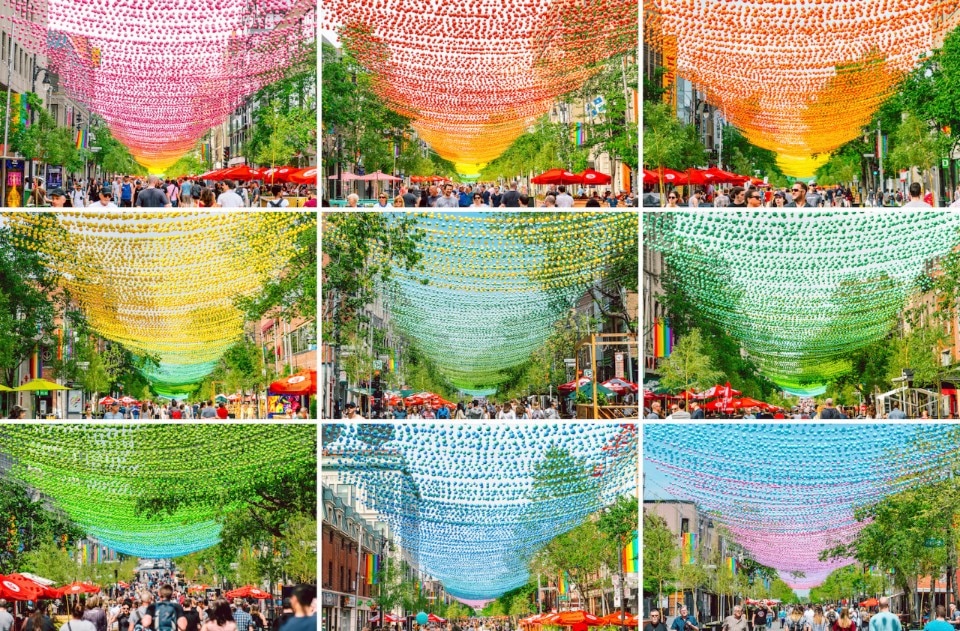

Discrimination and inequalities should be out! That is what the project of Canadian landscape architect and urban designer Claude Cormier shows: a rainbow street, a safe and equally accessible public space that should be exported everywhere, for everyone.

Indeed, our cities must provide room for diversity. Diversity in race, gender, character and taste that will guarantee a far more interesting and self-reflecting world.

In the meantime, the gap between the rich and the poor keeps growing all over the world, triggering tensions and wars.

It might help if we were all part of a giant middle class, enlarging wealth for all, extending the search for quality, and making investments in the fight against climate change that will have become affordable.

It might help to create and ensure access to work opportunities, schooling and housing for everyone.

It is quite alarming how unaffordable cities are becoming, and how serious the political and societal consequences of such a process can be if citizens are unable to afford the most basic need: an adequate home and a decent room. How do we deal with cities where nurses or police officers can no longer afford the cost of living? The decline of social-democratic parties all over Europe obviously runs in parallel with globalisation, but also with the unaffordability of housing.

In this issue we show the decline of social housing in New York and how the city is being gentrified, becoming more and more unaffordable and less and less diverse. New York is just one example, but this phenomenon applies to cities all around the world.

The solution to this housing crisis is, in my opinion, strikingly simple: at least 30 per cent of all new homes should be affordable. By imposing such a rule, urban societies will definitely be improved.

Some countries are already doing so, with new private developments only being allowed when mixed with 30 per cent of affordable housing. Some cities, such as Amsterdam, have gone even further by lifting this bar to 50 per cent of affordable housing.

Moreover, these regulations must ensure that affordable housing is distributed evenly, so as to make the wealthier areas of our cities part of this new form of egalitarianism.

But perhaps it would be better not to overly depend on private developers, and instead to finance social housing with taxes so that collective ownership can be maintained. In other words, a collective treasure.

The solution to this housing crisis is, in my opinion, strikingly simple: at least 30 per cent of all new homes should be affordable. By imposing such a rule, urban societies will definitely be improved.

When we started MVRDV in the 1990s we engaged in the very delicate issue of social housing, which was often applauded for some sense of humour and the use of colour. These are important design aspects that, when combined, can be very effective. In this issue of Domus, humour, colour and housing come together.

The social housing by MVRDV was praised because the Dutch government made it possible to create dwellings of high quality that allowed for differentiation. However, this is not always the case, and many social housing estates lack quality. Often, only the urban planning is of quality, while the architecture is sad, repetitive and lifeless.

It is for this reason that I love the work of Boa Mistura. This Spanish artist collective decided to turn the city into something colourful and artistic. They are not the first to choose this course of action – in the Brazilian favelas or the streets of Tirana we have already seen the use of art and colour as an urban tool. Yet we cannot stress enough how important it is to be creative, optimistic and transform the city into a nicer place, including these forgotten estates.

Many architecture magazines focus exclusively on best practices. What fascinates me is how little attention is given to the mediocre, which is built day by day all around us until suddenly it reaches a critical mass. In this regard, I have noticed in Germany that more and more competition winners look alike. Apparently, there is a trend for buildings with a facade made of narrow windows comparable to arrow slits, which I call the German birdcage. Yes, Max Dudler is the master of this kind of facade, and his buildings often have a strong sculptural quality in their consequent designs. But what about all the bad copies?

In this issue we discuss how the work of Ungers and Dudler is being copied into the mainstream, and how German cities are slowly being filled by this bird-cage architecture. No doubt many of these buildings are realised with social housing and green labels, but that is not enough. Genuine sustainability and true diversity make a wonderful, liveable city. Lovable architecture that will last longer than 30 years needs to be part of the sustainable and inclusive approaches to the fabrication of the city. Otherwise today we are creating a sort of bland architecture responsible for ugly buildings that we will either want to replace or, if that’s not possible, transform with an artistic makeover by Boa Mistura.