Nature has become a frequent word over the past decade. Yet in “feeling nature”, the emphasis lies less on “nature” than on “feeling”. In fact, feeling matters more. A nature unperceived remains an object: matter and phenomena, technology and science, materials and resources. That is not our subject. Feeling nature describes an affective bond between human beings and the natural world. Architecture that mediates this bond is not simply functional; it takes on a spiritual and poetic dimension.

There is a well-known story. Louis Kahn once asked Luis Barragán whether trees should be planted in the central plaza of the Salk Institute. Barragán answered with an argument for emptiness: leave it open, keep a facade towards the sky. It is, indeed, beautiful. I have visited the place many times. Beyond the blankness of the ground, there is also a blankness at the end of the axis: sea and sky are held together and placed at the centre of one’s vision. When I see someone seated on a bench, gazing towards the distant sky in quiet, stirred contemplation, I feel that person. When architecture enables us to feel the natural world we inhabit, we enter a deeper understanding – of the world, and of our own inner life. A dialogue thus begins.

The capacity of feeling nature is not new to us. Traditional art and architecture, East and West, have long embodied ways of relating to nature. What is new is how easily this capacity has been lost in the modern age of accelerating technology. In many Eastern traditions and philosophies, nature has long exceeded the categories of utility and material function. It became an extension of human imagination into the real world.

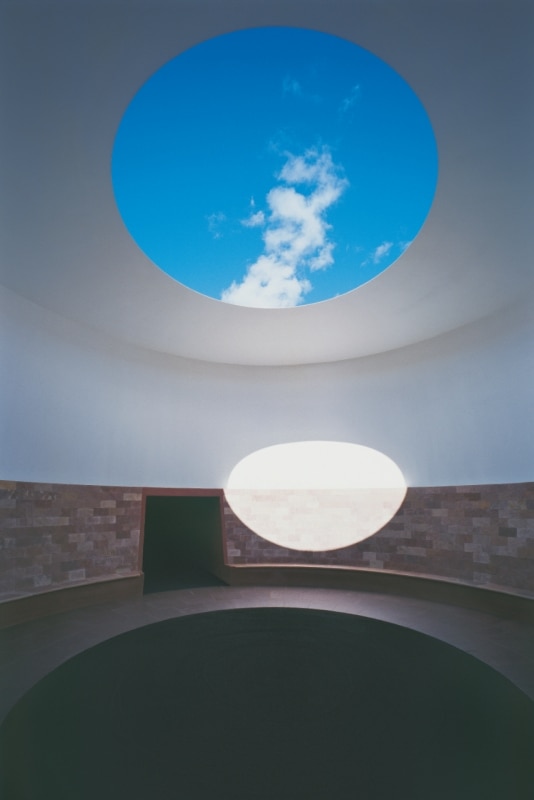

In landscape painting, mountains and rivers are not transcriptions of scenery but projections of an ideal condition of life. A garden, composed of rocks and plants, does not simply cultivate “greenery”; it opens a threshold into poetry. In karesansui, one may find only gravel and stone, yet an ocean appears – sometimes even a cosmos – an expansive spiritual world held within the mind.

A nature unperceived remains an object.

Ma Yansong

Even in classical urban planning, designers pursued the imagery of mountains, islands, lakes and seas, so that city dwellers might, in the course of everyday life, encounter nature’s poetic beauty. And yet fewer and fewer contemporary buildings can converse with nature in this poetic register. We have, in the way Le Corbusier anticipated, finally come to live inside the “machine”. The house as a “machine for living” offered architecture a shield – function, efficiency, economy – under which it gradually lost a core value: to be a shelter not only for the body but for the mind.

In Heidegger’s words, it should be a place where one may “dwell poetically”. Architecture should allow people to feel the beauty of nature, and through that, to feel life and one’s own existence. Yet the built environment produced by mass housing and urbanisation often feels cold, even indifferent. It no longer functions as a spiritual home, driving people to yearn instead for wild nature and virtual worlds. In the film Ready Player One, everyone builds an ideal world in simulation, while the real world collapses into a wasteland.

Today, architecture has begun to speak in the language of ecology and environmental responsibility: timber in place of more carbon-intensive materials; planted facades; AI systems that monitor and optimise energy use in response to local climates. Has architecture awakened? Perhaps – halfway. Yet for all its talk of nature, architecture often continues along an older path: it translates nature back into technology, treating it as object and resource. The architecture of the future should place greater weight on “feeling” nature – on rebuilding an emotional bond between humans and the world – so that living, and dwelling itself, becomes filled with poetic meanings. Even in strictly technical terms, technology is ultimately accountable to human feeling. In what appear to be purely functional advances in robotics and AI, perception and emotion remain central.

The house as a ‘machine for living’ offered architecture a shield under which it gradually lost a core value: to be a shelter not only for the body but for the mind.

Ma Yansong

I once had an interesting conversation with Sou Fujimoto about his vast circular “floating” park for the Osaka Expo 2025. Recently, controversy has arisen around the project: the massive amount of timber involved may be burned by the organisers rather than reclaimed. I joked with Fujimoto that the wood could be turned into Expo chopsticks – surely a more welcome afterlife than a bonfire. Yet what stays with me is not the material debate, but the experience the project proposes. A ring of that scale, lifted into the air, allowing people to walk – between land and sea – through the sky: an unprecedented, genuinely poetic encounter. When we argue about technology, we should not lose sight of what such encounters can yield: a quiet stirring of feeling, an inner resonance of living alongside mountains and water. Is that not what we should value most?

This issue asks whether future architecture and design can help restore an emotional bond between human beings and the natural world. Nature is not merely a physical presence; it is also what can be felt – and what we may enter into dialogue with. What we take from it, and what spirit we choose to articulate through it, tests the sensitivity and creativity of the designer. Here we have assembled a selection of distinctive works, tracing how different practitioners pursue these possibilities and how their explorations take form.

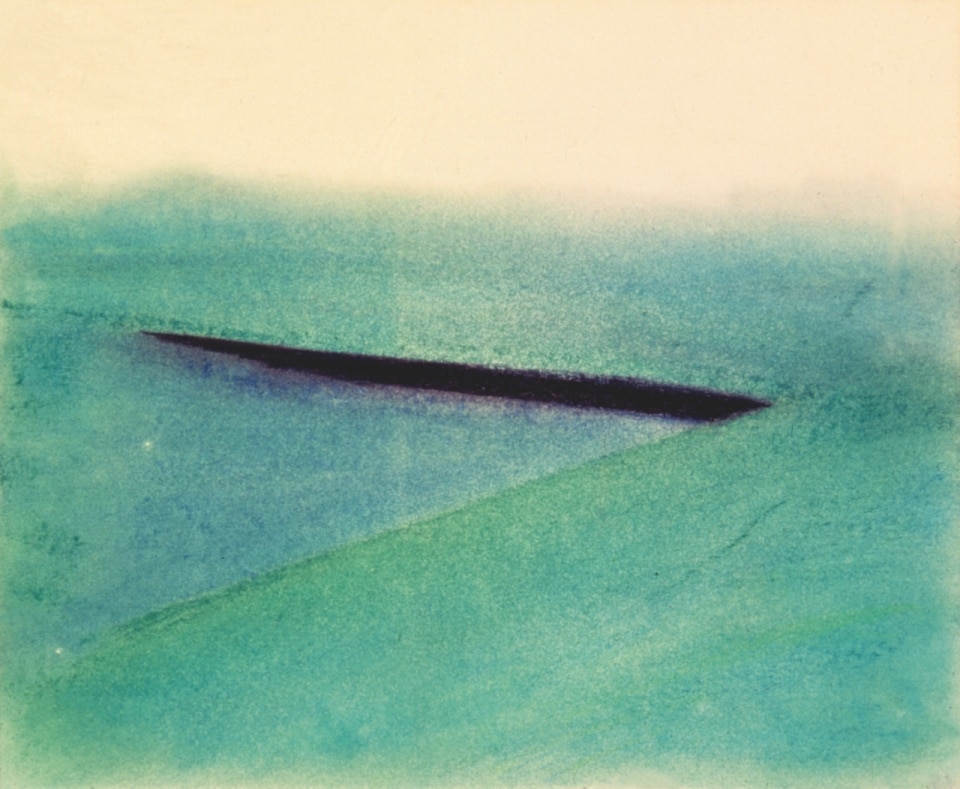

Overview image: Maya Lin Studio, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Washington, D.C., U.S., 1982. Photo © Maya Lin Studio/courtesy of Library of Congress