This is the final issue of my guest editorship of Domus.

The year has been a materialist odyssey into the world of architecture, art and design. A reminder that human society is shaped by the materials we harvest and manipulate to create the world we want to live in. Revisiting the material world in a journey from stone and earth, through metal and glass, to timber and textile, ending up with plant material and recycled material. As the final stop, we chose immaterial. The antithesis of the whole year. Designs untethered by their material medium.

The antithesis of solid material is immaterial abstraction. Considering something independently from its medium or source, this issue investigates the highest level of abstraction where the material is removed from any sort of expression. Like Jean Nouvel’s use of imagery replacing entire facades or surfaces with pictures. A design process migrating into Photoshop with the image as the source rather than the representation, and the architectural process becoming a material translation of the source image into reality. During Herzog & de Meuron's phase of imprinting imagery, they reduced a building’s form to the bare minimum in favour of converting facades into figurative images rendering glass and concrete as equals: a canvas for artistic imagery. Jeffrey Kipnis referred to it as anorectic architecture in his article The Cunning of Cosmetics (1997).

Immaterial can also be understood as the non-matter elements of the natural world, such as light, sound, temperature, gravity or space. Artists such as Olafur Eliasson or Drift find ways to make light, colour, temperature materially manifest, or to capture and reproduce the sensorial impact of flocking starlings or leaves blowing in the wind. Finally, immaterial can be understood as design and intelligence applied in its purest form to the virtual realm. My son Darwin is turning seven this month, and as part of his cognitive growth he has migrated his passion for Lego into the virtual world with his discovery of Minecraft.

Minecraft, as I see it, is the closest thing we have to a desirable and inhabitable mirror world. It teaches young minds how everything we take for granted needs to be resourced or mined, harvested, processed and recombined to become useful tools and technologies. As such, a virtual world requiring commitment, patience and celperseverance, not to mention intelligence, to an extent that makes the computer games of my childhood feel like Pac-Man compared to what my son and his generation can juggle in their minds.

The antithesis of solid material is immaterial abstraction. Considering something independently from its medium or source, this issue investigates the highest level of abstraction.

It would be almost anachronistic to pass a whole season of Domus without interrogating the latest player on the global art and design scene: artificial intelligence. As we all struggle to find our role as designers – or even as Homo sapiens – in a world increasingly driven by ever more powerful AI, I somehow see my own personal evolutionary journey as an architect as analogous to what awaits us all in the near future.

As a kid, I drew with crayons and watercolours. At the art academy, I had to learn how to draw with rulers and hard lines. I lost some of the feeling I had with my crayons, but I gained a new world of possibility to construct multipoint perspectives and measurable isometrics.

I then got a computer and learned to draw with a mouse. I lost the tactility of the physical pen on paper, but I gained a new world of 3D models, material mapping, daylight settings and space.

Today I draw with 700 brilliant, beautiful people. I have lost the control of holding the crayon. But I have gained a universe of possibility by engaging with all my powerful, thoughtful formgivers. It took me 25 years to assemble my team of naturally intelligent designers. Today, every young graduate has at their fingertips the productive and creative power of a global behemoth of artificially intelligent designers, engineers, filmmakers, researchers, etc. Even if it is hard to retain faith in our continued relevance, there is no doubt that AI promises a new equality where creative power is unrestrained by wealth, age, education or even intelligence.

To kick off this issue, we have Tobias Rees exploring quantum computing and consciousness. David Sheldon-Hicks writes about mapping the future in the great fictions of the big screen. We met with Olafur Eliasson to talk with him about his work making the immaterial tangible.

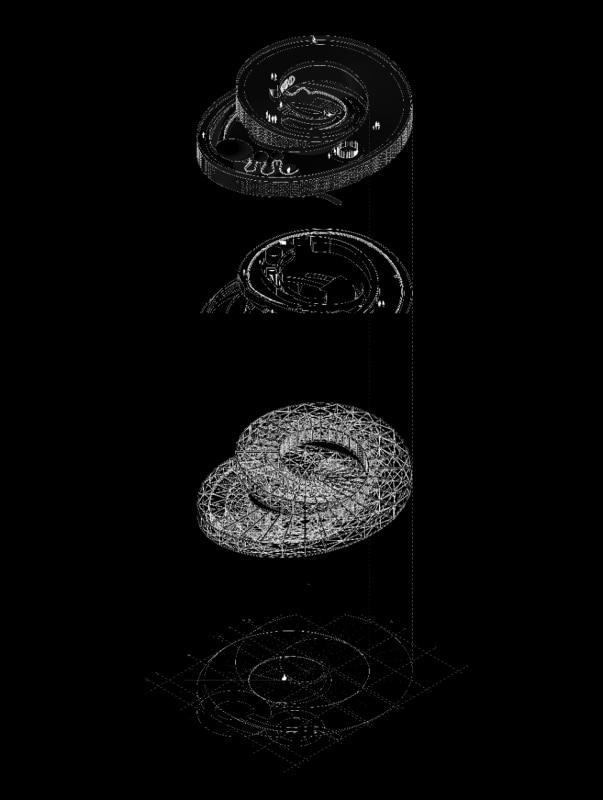

Matt Shaw describes the Sphere as a sort of final state of architecture, where all surfaces have been taken over by ephemeral content. AquaPraça by Höweler + Yoon and Carlo Ratti Associati is a floating square materialising the intangibility of rising water levels. Fran Silvestre’s Camiral House is both anti-tectonic and immaterial, making his built work indistinguishable from the abstract renders blurring the separation between fiction and fact. Mariko Mori’s Yuputira House combines abstract white finishes with curvilinear geometries to dissolve both form and substance. Carlos Bañón and Daeho Lee are both early pioneers in exploring the aesthetic potential of AI as a source of authorship, while Delfino Sisto Legnani documents the physical reality of AI infrastructure.

In a way, Anadol’s materialising of the virtual world represents for me the next frontier of architecture, art and design. And makes ‘immaterial’ the obvious ending to our materialist odyssey. From quartz to quantum.

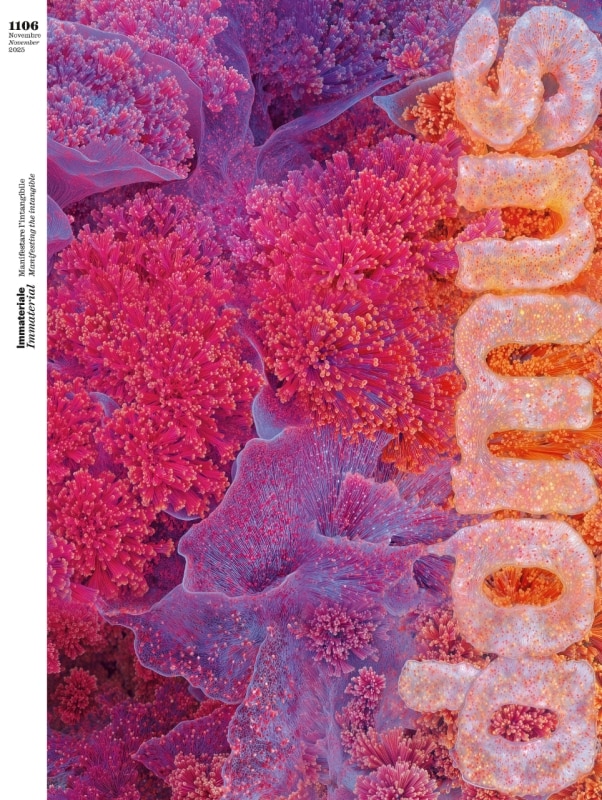

Nendo minimise material expenditure to its physical limits. Retinaa’s designs for the new Swiss passport explore graphic complexity in the service of security. Humans since 1982 combine the analogue and the digital to create artworks of emergence and time. TeamLab explores the immersive with their inhabitable animated artworks, while Reuben Wu deploys drones to draw cathedrals of time and light. In Molecular Landscapes, Evan Ingersoll and Gaël McGill give tangible mechanical reality to the complex processes inside living cells. Zimoun uses ready-made materials to materialise the audible. Anton Repponen stretches time into Mondrian-esque snapshots of everyday moments. Ralph Nauta and Lonneke Gordijn explore the oxymoronic nature of their work at the intersection of freedom and control, artificial nature and weightless mass. And finally, Refik Anadol gives material form to the digital with his free-flowing AI-generated fictions. With his cover art, he uses large language models to create fictitious coral constellations, reminding us of the similarities between the natural algorithms that occur in living systems and the digital calculations in computer hardware. In a way, Anadol’s materialising of the virtual world represents for me the next frontier of architecture, art and design. And makes “immaterial” the obvious ending to our materialist odyssey. From quartz to quantum. In my time as an architect, we’ve achieved great leaps with CAD and BIM. The degree of sophistication in simulation, modelling and documentation has been ever escalating.

Yet when it comes time to build, we still plot blueprints for guys with hammers.

Our Danish Pavilion at the Shanghai World Expo was documented entirely in BIM with millimetre tolerances. When it became time to execute the curvilinear box truss, printed schematics were transferred by hand and with chalk to sheet steel, and then cut and welded by hand. The thickness of the chalk alone was 10 times our design tolerance. The accuracy of the immaterial disintegrated at the first encounter with the material world. A loss of fidelity literally beaten into shape with the use of a sfuvery large hammer. Today, we seem to be at the cusp of unleashing practical robotics into our daily lives.

During Herzog & de Meuron's phase of imprinting imagery, they reduced a building’s form to the bare minimum in favour of converting facades into figurative images rendering glass and concrete as equals: a canvas for artistic imagery.

Driverless Waymos in California. Roombas and lawn movers. Optimus Teslas and Icon’s 3D house printers. Once robotic manufacturing and construction arrive at scale, we will move seamlessly from data to matter without losing definition in translation. AI in the material world will also cure the jarring shortfall in AI’s current ability to design and comprehend architecture.

Large language models excel only where good data exists. A text is the final product of a text. An image, the final product of an image. But a picture of a building is as much the sum of the building as a picture of a plated meal is the same as the meal itself. It says nothing about the taste and texture, the spice and satiation of each bite. Similarly, you need to connect multiple data points, visual and physical, plans, sections, 3D models, material samples and images to comprehend a work of architecture.

Right now, LLMs lack access to coherent data. But once our robots, bipeds and drones roam the physical world freely, AI will begin to understand what architecture and urbanism is all about. That to me is one of the greatest frontiers ahead of us. In a way, the Kurzweilean singularity of the world of form-giving. What happens once the artificial and the virtual is given physical form and agency to explore and impact our actual natural environment? Bringing the immaterial into the material world. Immaterialism.

It has been an honour and a privilege to serve as guest editor in 2025.

I thank you for your time and attention.

Bjarke Ingels signing off for now.

Opening image: Bjarke Ingels Group for Artemide, the color spectrum of Dusk, a wall washer by BIG, 2025. Courtesy Artemide