Andrea Branzi arrived in Russia, presumably in 1962, to visit his brother, who was a Rai correspondent in Moscow, and there, in the capital of Soviet socialism, he briefly became a photographer. He was twenty-three years old and studying at the Faculty of Architecture in Florence: just a few years before the founding of Archizoom and the theorization of the No-Stop City.

Humboldt Books, in the volume Moscow 1962, collects this journey and the previously unpublished photographs that accompanied it.

In the early 1960s, there was a lot of the West in the Soviet Union. Rock music appeared on Russian stages, Coca-Cola entered homes, and portraits of Ernest Hemingway—antifascist, “independent leftist,” but also strongly anti-totalitarian—adorned the rooms of young Russians born under Stalin.

From Berlin, Alfredo Cohen, Franco Battiato and Giusto Pio wrote Alexander Platz—the song that made Milva famous outside the theaters—to tell the experience of many young Italian artists who moved to the eastern side of the Wall to experience life in the Soviet Union, a life seemingly opposite—at least apparently—to capitalism.

Among the intellectuals, artists, writers and musicians trying to understand what was happening in Moscow was also Andrea Branzi, master of radical design, “spiritual guide”—as Ugo La Pietra called him—of Archizoom. Branzi himself had written in Domus issue 633 that contemporary cities were no longer defined by architecture but “by the market, by the goods circulating within them” and that designing, consequently, also meant creating “a new metropolitan life” that took this fact into account.

Communism [in this sense] represented the ‘new’, a general openness whose possibility could be felt.

Stefano Sonnati, professor of philosophy and friend of Andrea Branzi

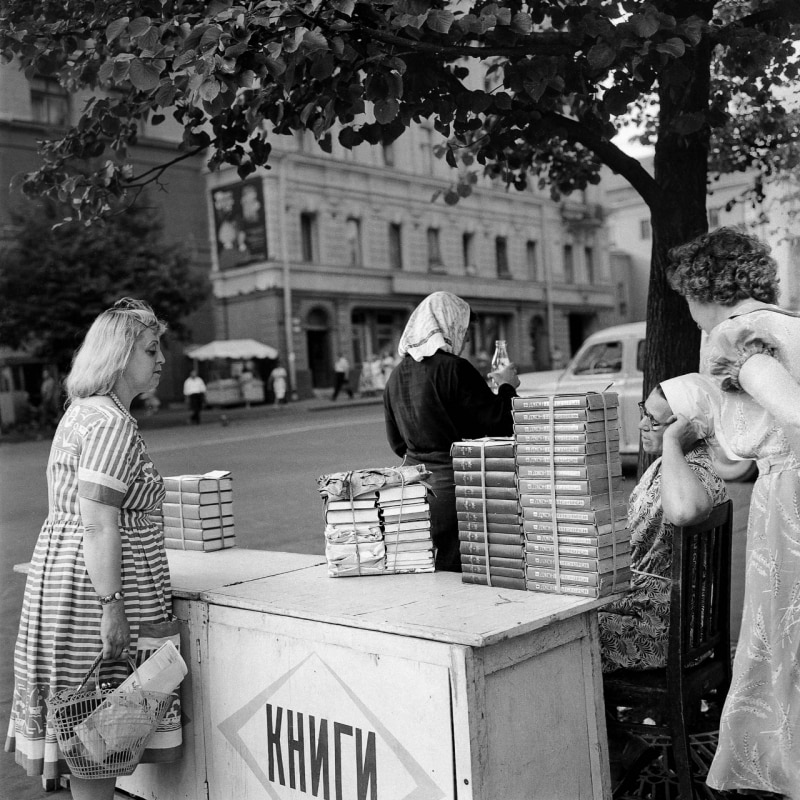

The volume Moscow 1962 contains more than fifty black-and-white photographs. The collection is accompanied by texts from historian Gian Piero Piretto and researcher Angela Rui, who explore the state of socialism when Nikita Khrushchev, after Stalin’s death, loosened the regime’s grip and allowed even “foreigners” to cross borders that had seemed impenetrable.

As Stefano Sonnati, philosophy professor and close friend of a young Andrea Branzi, recounts in the book’s outro:

“In the Branzi household, the rosary was recited every evening. And it was normal in the family that women did not pursue studies. Communism [in this sense] represented the ‘new,’ a general openness whose possibility could be felt.”

In Branzi’s photographs there is a certain air of suspension, a premonition, perhaps, that something was about to explode at any moment, the feeling that the Soviet dream was already a dream without spectators. Streets and parades appear empty, markets bare, plates without food, books without bookstores.

The only people walking Moscow’s streets are women and children, often photographed in front of propaganda posters and immersed in the shop windows of emerging American-style commercial chains. Men appear very little: they are in factories producing weapons for a war (the Cold War) fought more with assembly lines than with guns.

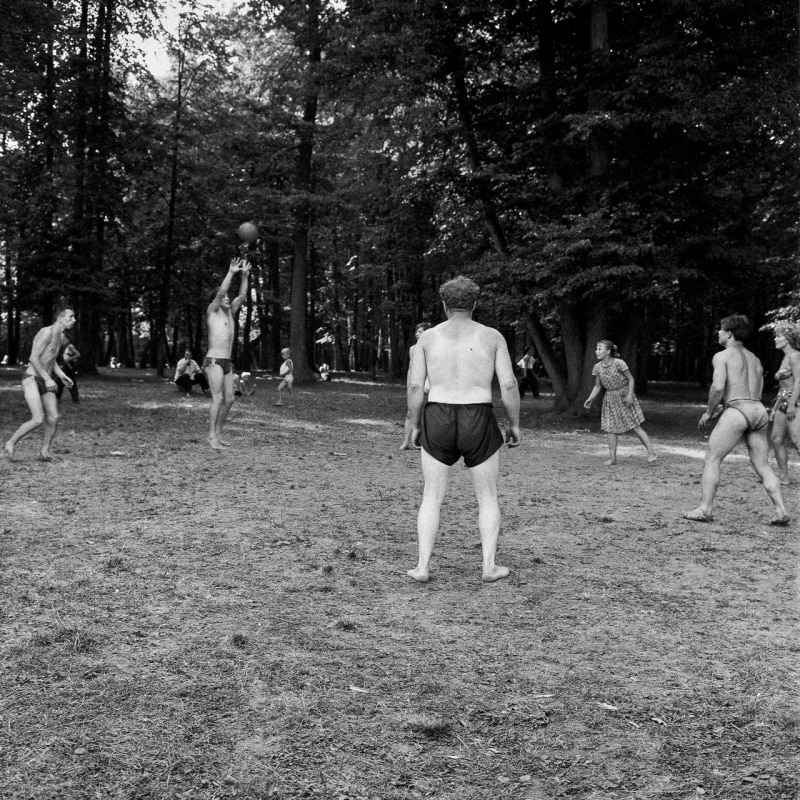

The only real crowds in Branzi’s deserted photographs are on artificial beaches: incredible Soviet-era architectural oases built on the Moskva River and nearby lakes. Often free or low-cost, these city “beaches” embodied all the new principles of Soviet policy: accessible leisure spaces and generalized wellbeing for the population.

Even the many photographs of Moscow’s architecture reveal the wonder of the Florentine designer and architect at a city of stark contrasts. Squares with imposing Stalinist “palaces of power” sit alongside the remnants of Tsarist architecture. Churches have disappeared, converted into swimming pools, wunderkammers, or museums. In Moscow’s outskirts, the first Khrushchyovkas—the low, minimal residential buildings commissioned by Khrushchev to respond to the housing crisis—begin to appear. All of this is wrapped in fog. The future we see through Branzi’s eyes is already a missed future.

Moscow 1962 is the twenty-fifth volume of Humboldt Books’ Time Travel series. The series, launched in 2015 with Iran 1970—an unpublished reportage by Italian photographer Gabriele Basilico—celebrates its tenth anniversary this year, gradually extending its collection to include photographic testimonies from “non-photographers,” amateurs who, as in Branzi’s case, left photography at the margins of their careers.

The volume, released in Italy on Wednesday, October 22, will be presented on Friday, November 14, 2025, at 6:00 p.m. during BookCity 2025—the literary festival annually promoted by the City of Milan—at the Sforza Castle, with interventions by Enrico Morteo and Valentina Parisi.

- Show:

- La giovane Russia. Mosca 1962 nelle foto di Andrea Branzi (Young Russia. Moscow 1962 in the photos of Andrea Branzi)

- Where:

- Castello Sforzesco, Bertarelli Hall

- Dates:

- November 14, 2025

- During:

- Bookcity Milan 2025

All images: Photo Andrea Branzi @ Orsola and Lorenza Branzi-Andrea Branzi, Moscow 1962, Humboldt Books, Milan 2025