David Lynch was an audiovisual artist. He conceived films by creating images and environments, forging handcrafted sounds. This process often came before screenplays (which he did write, inspired by “ideas” that had more in common with visions than inventions). Of course, this wasn’t true for all his films. Some were commissioned and linear (The Elephant Man), while others were linear by his own desire (The Straight Story). But in most cases, his films featured experimental video art creations interwoven into the flow of a story—or the outline of a story—designed to stimulate intuition.

Narrative always exists in his films, but it doesn’t necessarily follow conventional cause-and-effect relationships. More often, it aims to lead the viewer on a journey of abstraction rather than logic.

In general, it’s fair to say that most of David Lynch’s films function like video art, adhering to the same principles: the part that must be understood rationally is minimal compared to the part that must be interpreted subjectively. What very few, if any, have achieved like Lynch is his ability to tap into the collective unconscious and generate images that are both enigmatic and striking to a broad audience. Despite being an esoteric artist, Lynch managed to reach a wide enough audience to make multiple films in Hollywood, where box office success is the only condition for continuing as a director. The thrilling mystery he infused into his creations invited exploration, engagement, and the negotiation of meaning.

The result of this approach is that the imagery Lynch created is far more memorable than the plots, characters, or stories of his films, which few can recall. For example, Dennis Hopper’s unsettling criminal inhaling helium through a transparent mask in Blue Velvet, producing one of Lynch’s quintessential mechanical white noises; the road at night, partially illuminated by headlights in Lost Highway; the monstrous crying baby at the end of Eraserhead; the two women witnessing a haunting performance in Mulholland Drive; the rabbit family in INLAND EMPIRE; and one of his latest: a slow-motion atomic explosion, the source of pure evil, from Twin Peaks: The Return.

However, Lynch’s most spectacular visual achievement, albeit the least “aesthetically pleasing,” is the transformation of traditional Americana into the threshold between our world and the transcendental. He achieved this through the desecration of its interior design.

In Twin Peaks, Lynch manipulated the classic American mid-20th-century aesthetic—small-town life, convertible cars with gel-haired boys and blonde girls in poodle skirts, suburban homes, pristine interiors, diners with uniformed waitresses, sawmills, sheriffs, and the architectural style of northern U.S. mountain towns—and merged it with another realm entirely born of his imagination: the Black Lodge.

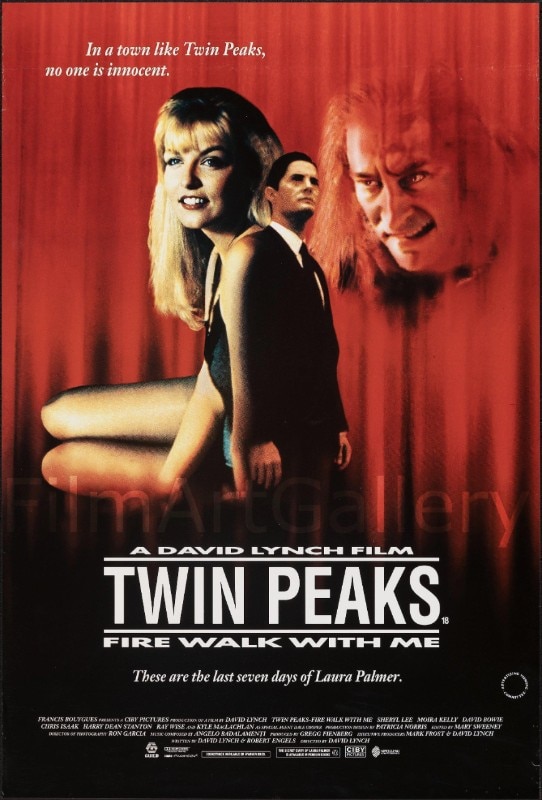

The Black Lodge in Twin Peaks is a room—or series of rooms—framed by red curtains, with a zigzag black-and-white floor, sparse furnishings like black armchairs, standing lamps, a table with a lampshade, and occasionally classical statues. If Twin Peaks represents the epitome of traditional, deep America, the Black Lodge epitomizes the metaphysical—a space between life and death that defies cause-and-effect logic. According to the show’s philosophy, which aligns with Lynch’s, it’s a place where answers or, at least, clues to greater awareness are most accessible.

The entire narrative of Twin Peaks revolves around the collision of this other dimension with our world, conveyed through decor. The series’ violence always impacts symbols of mass American design—cars, stages, or consumer objects. In one of its most iconic and chilling scenes, BOB, an entity that feeds on pain and suffering, crosses a quintessential suburban living room, trampling over sofas and coffee tables to confront the viewer. It’s as if this malevolent force must first violate the spaces we inhabit and their furnishings to infiltrate us.

The bourgeois families of Twin Peaks mirror those at the beginning of Blue Velvet: embodying a propaganda-like vision of immaculate, polite, formal Americana, hiding decay and secrets that destroy them from within (in Blue Velvet, the bourgeois opening ends in death). They conceal BOB, who moves through their living rooms or, in another unforgettable image, hides—without truly hiding—behind Laura Palmer’s bed.

Like the Surrealists, Lynch was always enamored with the boundary between the real and the dreamlike, between what we can say exists and what lies beyond physics. For Lynch, however, it was always a matter of interiors. More important than anything was sound—continuous noises or electronic soundtracks—but immediately after sound came space. The densely packed interiors of the Palmer house, with its abundance of elements, paintings, and wallpaper, contrast with the vast emptiness of the Black Lodge. Full versus empty, traditional versus modern, comforting versus experimental, harmonious (seemingly) versus distorted (seemingly). White versus black. While his films often use basic contrasts, what is far from basic is how these elements are rendered through objects, styles, trends, and furnishings that surround us.

Lynch was deeply attached to the 1950s—their aesthetics and the ideals they promoted. Music, costumes, hairstyles, and objects from the ’50s appear in nearly all his films. Twin Peaks is one of the clearest examples of how he used these references, particularly interior design, not to explain but to suggest something about the reality we live in. The series can be interpreted as a clash of decor ideologies. On one side, the reassuring, colorful sofas and cushions, tainted by the evil that killed Laura Palmer and lurks among the suburban calm. On the other, Dale Cooper’s journeys into the Black Lodge, a mystical space unlike anything that existed before Lynch, more aligned with sophisticated modern decor than traditional mysticism.

As Tim Burton explored contemporaneously, the peaceful, pastel bourgeois living rooms are home to evil—barely hidden—while in the unsettling Black Lodge, where speech is reversed, and events are obscure, one can encounter Laura Palmer, discover truths, and confront one’s double.