This article was originally published on Domus 1061, October 2021.

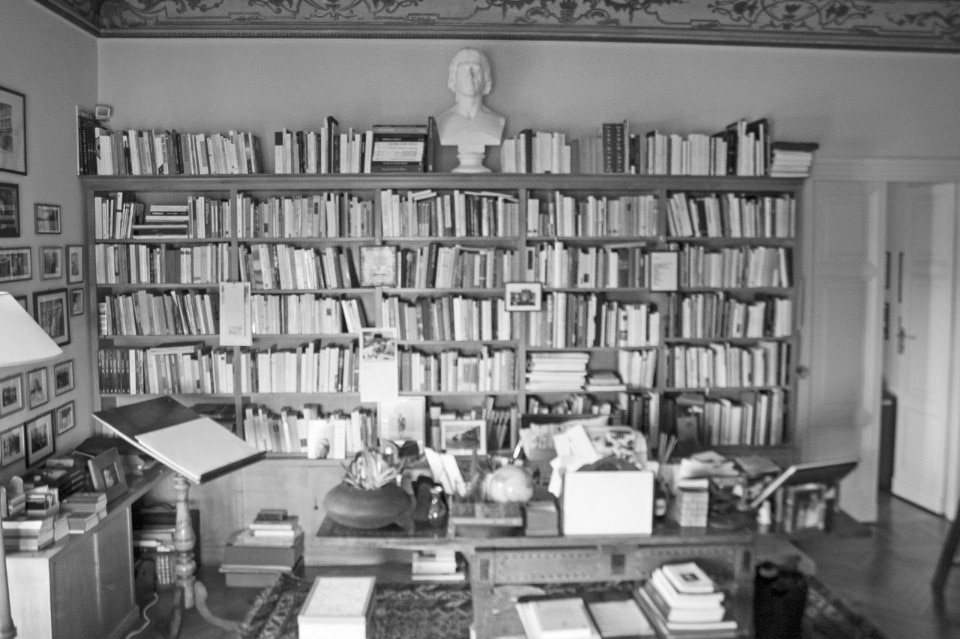

“I’m my circumstances.” We are that which surrounds us. For this reason, the home is essential, because it is the skin of the circumstances in which we live, our immediate setting, our shell, whether rich or poor barely matters. “Once it was filled with symbols, objects, memories. But today homes, especially those of the very wealthy, are like operating theatres, cold and sterile. Perfect symbols of the effacing of the past replaced with the populist presentism of our own time. The problem is that the home still shows people’s souls, as in every age. If you want to know someone, talking to them is not enough, seeing them counts little, observing their gestures is more. Only by observing them in their homes can we grasp who they really are. Because the home never lies.”

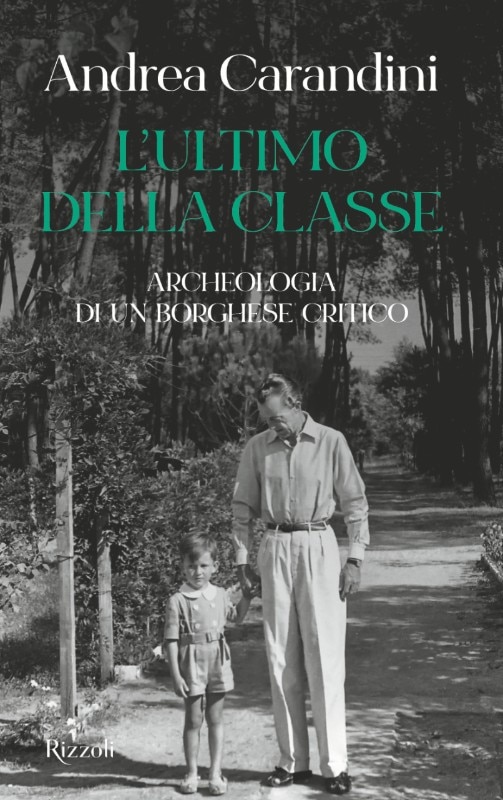

In a truly extraordinary life, Andrea Carandini has been many things. Aristocrat, archaeologist, academic, intellectual, politician, traveller, man of letters and finally penitent bourgeois and critic. This appears in L’ultimo della classe , a biography that is more than an intellectual record. It retraces his secret pleasures and pains through the smallest actual relics, psychoanalytic and pharmacological. The son of Nicolò Carandini, first ambassador to London after the war, and the grandson on his mother’s side of Elena, the daughter of Luigi Albertini, the editor (and owner) of the Corriere della Sera who left Via Solferino in 1925 rather than kowtow to Fascism, Carandini is a world authority on 20th-century archaeology, in which he embodied the scholarly method discussed in his thesis supervised by his mentor Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli.

The author of the revolutionary discovery, on the slopes of the Palatine Hill, of the remains of a masonry fortification dating from the 8th century BC, which rewrites the origins of Rome because in line with the legend of Romulus and Remus, Carandini has expanded our knowledge of Roman villas and their relations with the systems of production and slavery.

A study of homes, things and souls that half a century later he has decided to turn on himself, without the least indulgence. “I feel like the last of the Mohicans. I’m one of a group that may include other survivors that the country calls on in dramatic times. But they’re no longer a group or class. They are scattered, lonely, isolated individuals. They don’t mix or recognise each other, or if they do, they don’t dare appear. It would be impossible when there are no longer salons, schools run by political parties, parishes or military service. Intermediate bodies, the rites of belonging and myths of initiation that defined a certain world for better or worse. A few days ago I met a still young and attractive woman who wanted to join a commune to avoid being alone.”

Carandini’s remorse is that this fragmentation was not understood in time, especially by those who, like him, had a duty to do it for the sake of culture and background. “I’ve made many mistakes in my lifetime, including the serious one of thinking these things were not important.” Among them we might include an infatuation with Communism, thought it did not last long and was followed by self-criticism, unlike many comrades equally bourgeois but much less critical. “You’re right, but in the 1970s the country was still in the grip of tradition. The fatal metamorphosis began in the eighties, quickened in the nineties and became irreversible in the 2000s driven by Internet. Since then everything has become deranged, the home has collapsed and what you see is a new, unrecognisable world. The problem hardly affects me, given my age, but it makes me more nostalgic and lonely.”

And to think that Carandini always affirmed his independence. Not only in the “philology of things” versus the “philology of the word”, but even more of thought and action. In this he took after his grandfather Luigi, who refused to submit and withdrew to his farm at Torre in Pietra. And also his mother Elena, who turned the rules of her time and rank into a self- education that was above all a path to independence and freedom. “No, the loneliness I’m talking about has nothing to do with the independence that I claim as the most precious asset inherited from my family. I terribly miss frequenting elevated, diverse, brilliant people. Fortunately everything is mitigated by a beautiful family that consoles me, but it cannot efface the memory of a world where everyone engaged in social rituals, not just the bourgeoisie. Family friends, discussions, solidarity, dinners. Without this exchange taking place in homes, the mind atrophies.”

Homes again mark the existential and cultural journey called life. Life on the Quirinal, where Carandini was born and went back to live, and the other on the estate of his grandfather at Torre in Pietra. The Villa dei Ronchi of his youthful holidays in Versilia and the villa on the Argentario of his maturity. But also the apartment in Trastevere, which marked his separation from his family, and the small house at Deià in Majorca, the last Eden from which Carandini speaks to Domus.

“The source of the evil is not the end of the home, but the death of education. The Gentile Reform was an excellent reform that created an excellent school. Noble, free, recognised by both sides of the political spectrum. Gentile’s aim was not to train professionals but citizens in the whole sphere of life. In order to do this, humanistic culture was and is essential, even more than a scientific culture, especially today when the ancient traditions handed down by the aristocracy, the bourgeoisie and the enlightened classes no longer exist.

When individuals feel lonely and abandoned, they turn to drugs to bear the burden of living. Hard drugs like chemical ones or soft drugs like technologies, symptoms of the void that the history of humanity has become. This is the sad and central point because, as life has taught me, history is not about the past but the future. It is a force, a lever, an energy not to look back, but to move forward.”

- Opening image :

- Andrea Carandini’s study. The photos are taken from Andrea Carandini’s book, L’ultimo della classe , Rizzoli, 2021