The Fountainhead residence, also known as the Hughes House after J. Willis Hughes, the client and oil magnate, is located in Jackson, the capital of the state of Mississippi, in the Fondren neighborhood. Built in 1949, it is one of the last among the more than five hundred works constructed over seventy years of Frank Lloyd Wright’s career, whose complete list can be found on the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy website.

After spending almost seven years on the real estate market, with an initial asking price of more than 2.5 million dollars, the Hughes House was purchased for one million by the Mississippi Museum of Art, the largest modern and contemporary art museum in the state, which plans to restore it and then open it to the public—for guided tours by appointment—for the first time in decades.

View gallery

View gallery

Frank Lloyd Wright, Home and Studio, Oak Park, Chicago, Illinois 1889

It all started here: the home/studio that Wright designed when he was only 22 years old, the first building conceived in total creative autonomy. Built in the shingle style that was popular on the East Coast at the time and inspired by colonial tastes, the work features an asymmetrical facade, a large veranda and external envelopes in wood “shingles”. Despite the still immature language, the building contains the germ of a revolutionary thought and openly critical of the rigidity and pretentiousness of Victorian houses, preferring a free plan and a more gentle and sustainable relationship with the natural environment: these are the founding elements of future prairie houses.

Photo by Michael Clesle. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois 1910

Robie House is the summa of the precepts that Wright elaborated in the first decade of the twentieth century around the theme of the prairie houses, the model of the house conceived in explicit negation of the magniloquent and affected language of neoclassicism then prevailing: a house that anticipates the attention for environmental sustainability, made of lowered volumes, wraparound and protective roofs, straightforward and natural materials (such as wood and brick), free plan, absence of decorative devices and dialectical relationship with the natural context.

Photo by Teemu008. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois 1910

Photo by David Arpi. Courtesy Creative Commons

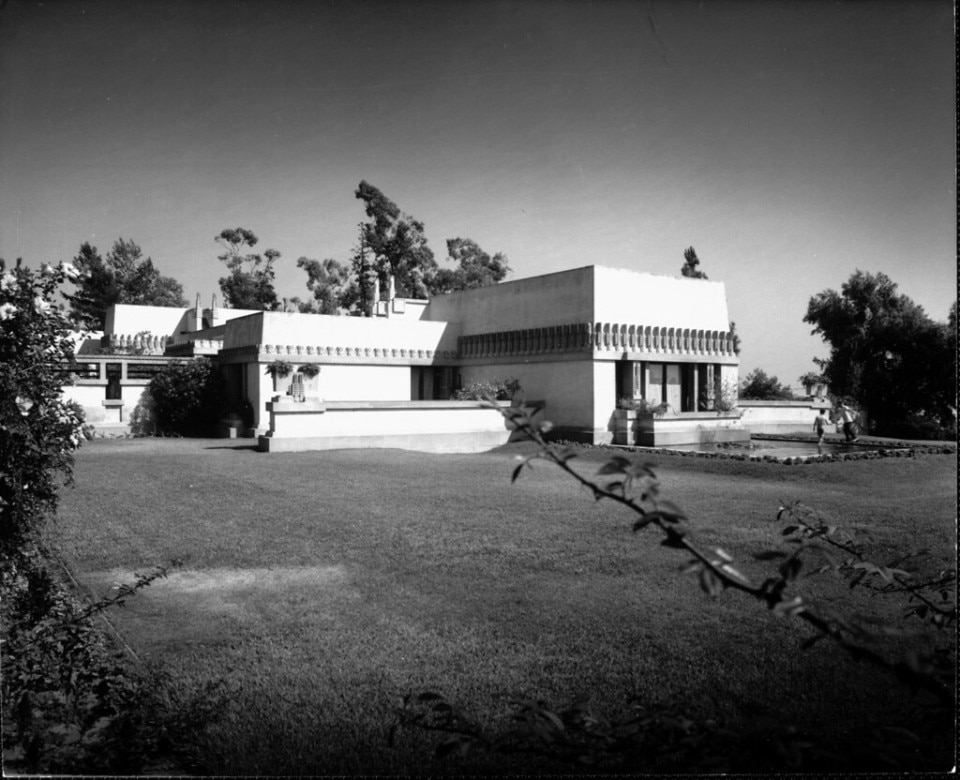

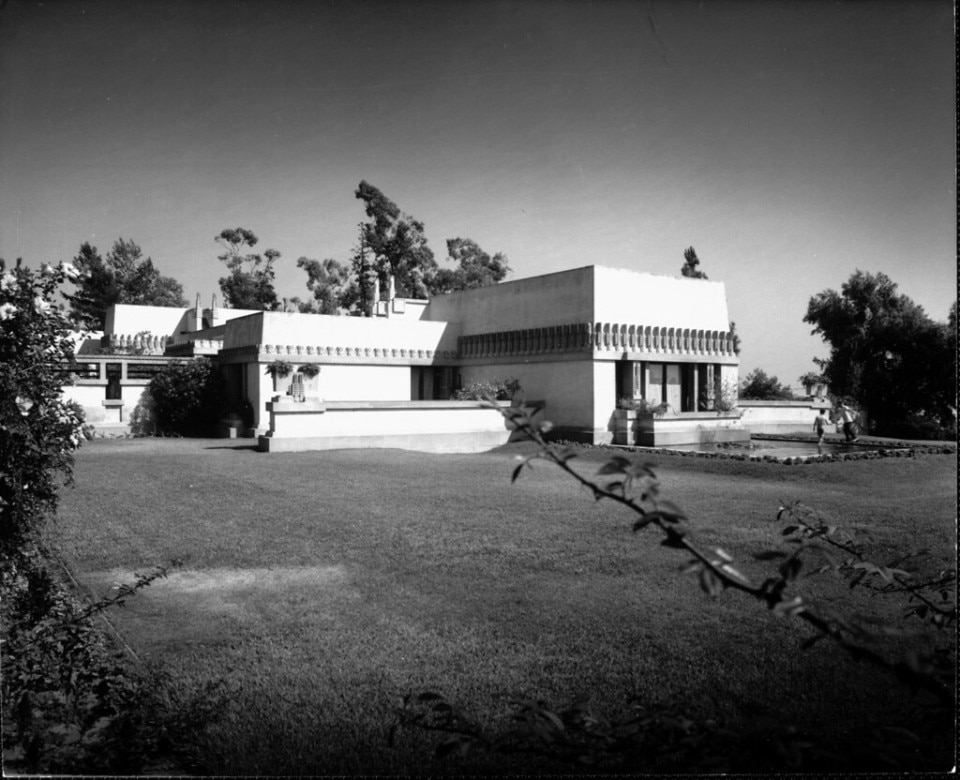

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hollyhock house, Los Angeles, California 1921

Despite the dazzling sunshine and clear skies of California, Wright's time on the West Coast in the 1920s was clouded by gloomy and pensive moods, probably due to troubled personal affairs. The result was a stark and unsettling design language that is embodied in Hollyhock house, a home commissioned by oil heiress, philanthropist and socialite Aline Barnsdall in the East Hollywood neighborhood. The building refers explicitly to pre-Columbian culture, with massive concrete blocks, bas-reliefs and decorations in the style of an "Aztec temple" (without sacrificial altars, at least at first glance).

Photo by DB’s travels. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hollyhock house, Los Angeles, California 1921

Photo by Fæ. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona 1937

Wright said that “Taliesin West is a look over the rim of the world.” In fact, it is a reality in its own right that claims its own autonomy from the ordinary and often overwhelming gears that govern daily life. Here, in the desert, the architect conceived his buen retiro from the rigid winters of the Mid-West and from the convulsive metropolitan rhythms, as well as a laboratory for training and experimentation for his students. The work was almost all built by the master and his apprentices and is inspired entirely by the desert landscape, with low volumes framed by redwood beams and native materials such as rock, concrete mixed with local materials and desert sand. Today it is the home of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

Photo by Teemu008. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona 1937

Photo by Tatiana12. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hanna-Honeycomb House, Stanford, California 1937

The Hanna-Honeycomb House, named for its hexagonal plan and the first non-rectangular building Wright designed, was a simple, functional, and affordable middle-class design. The 1.5-acre lot included a guest house, hobby space, storage, double garage and garden shed. In keeping with the Usonian style, the homey, family-oriented aura of the horizontal volume building is provided by straightforward, natural materials such as wood and brick and by flexible, light-filled rooms with floor-to-ceiling windows that punctuate the elevations. Today the building is owned by Stanford University.

Photo by Teemu008. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hanna-Honeycomb House, Stanford, California 1937

Photo by Wallyg. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater (Kaufmann House), Mill Run, Pensylvania 1939

Wright said that “if you listen to the sound of Fallingwater you hear the stillness of the countryside”. And indeed, there is nothing more wonderfully intimate and pacifying than finding, nestled comfortably in the protection of a home retreat, the sounds of the forest. Nestled among the hills of Mill Run on the natural waterfall of Bear Run, the house with its disruptive cantilevered volumes clad in quarry stone is a passionate declaration of love by the designer to Nature and underlies a relentless search for a balance between Man, technology and landscape.

Photo by Orangejack. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater (Kaufmann House), Mill Run, Pennsylvania 1939

Photo by Kevinq2000. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Rosenbaum House, Florence, Alabama 1940

If one thinks of the Usonian architecture that depicted houses conceived specifically for the American middle class, small in size, simple but elegant and moderately priced, one cannot but remember Rosenbaum House, the only one designed by the master in Alabama and which embodies all the characteristics of this "style": "L" plan, single level, functional and flexible distribution, full-height windows, furniture incorporated into the structures and simple and natural materials such as wood and brick. After the death of the owners, it was purchased by the municipality of Florence and today houses a museum.

Photo by string_bass_dave. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Rosenbaum House, Florence, Alabama 1940

Photo by string_bass_dave. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Cedar Rock, Independence, Iowa 1950

Under the banner of gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), nothing was left to chance in this small house commissioned by a wealthy local family, from the design of the architecture to the furnishings and tableware (all designed by Wright). The building is a clear example of a single-level Usonian house, with flat roofs with projecting and protective pitches, an open and flexible floor plan, brick walls, wood window frames, full-height windows, and concrete floors. After the owner's death, the house was donated to the state of Iowa, which still retains ownership.

Photo by L.M. Bernhardt. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Cedar Rock, Independence, Iowa 1950

Photo by L.M. Bernhardt. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Kentuck Knob, Dunbar, Pennsylvania 1956

Designed at the ripe old age of 86 by the master, Kentuck Knob was one of the last houses Wright built. In the style of the Usonian, the single-story house with its vast cantilevered flat roofs of copper sheeting contrasting with the neutral tone of the natural stone of the walls, free-standing interiors finished in sandstone and North Carolina red cypress wood, the house has the peculiarity of a hexagonal plan but the usual recognizable grace in blending delicately into the natural landscape.

Photo by sarowen. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Kentuck Knob, Dunbar, Pennsylvania 1956

Photo by sarowen. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Muirhead Farmhouse, Kane County, Illinois, 1953

The house, the only farmhouse Wright ever designed, is in effect a ranch set on an 800-acre prairie, in the style of the Usonian lexicon that here employs squared volumes on a single level, generous flat roofs with massive brick walls, concrete finishes mixed with local materials and Tidewater red cypress. The building, which has undergone several renovations, is still owned by the family, which makes it visitable at certain times of the year.

Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Home and Studio, Oak Park, Chicago, Illinois 1889

It all started here: the home/studio that Wright designed when he was only 22 years old, the first building conceived in total creative autonomy. Built in the shingle style that was popular on the East Coast at the time and inspired by colonial tastes, the work features an asymmetrical facade, a large veranda and external envelopes in wood “shingles”. Despite the still immature language, the building contains the germ of a revolutionary thought and openly critical of the rigidity and pretentiousness of Victorian houses, preferring a free plan and a more gentle and sustainable relationship with the natural environment: these are the founding elements of future prairie houses.

Photo by Michael Clesle. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois 1910

Robie House is the summa of the precepts that Wright elaborated in the first decade of the twentieth century around the theme of the prairie houses, the model of the house conceived in explicit negation of the magniloquent and affected language of neoclassicism then prevailing: a house that anticipates the attention for environmental sustainability, made of lowered volumes, wraparound and protective roofs, straightforward and natural materials (such as wood and brick), free plan, absence of decorative devices and dialectical relationship with the natural context.

Photo by Teemu008. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois 1910

Photo by David Arpi. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hollyhock house, Los Angeles, California 1921

Despite the dazzling sunshine and clear skies of California, Wright's time on the West Coast in the 1920s was clouded by gloomy and pensive moods, probably due to troubled personal affairs. The result was a stark and unsettling design language that is embodied in Hollyhock house, a home commissioned by oil heiress, philanthropist and socialite Aline Barnsdall in the East Hollywood neighborhood. The building refers explicitly to pre-Columbian culture, with massive concrete blocks, bas-reliefs and decorations in the style of an "Aztec temple" (without sacrificial altars, at least at first glance).

Photo by DB’s travels. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hollyhock house, Los Angeles, California 1921

Photo by Fæ. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona 1937

Wright said that “Taliesin West is a look over the rim of the world.” In fact, it is a reality in its own right that claims its own autonomy from the ordinary and often overwhelming gears that govern daily life. Here, in the desert, the architect conceived his buen retiro from the rigid winters of the Mid-West and from the convulsive metropolitan rhythms, as well as a laboratory for training and experimentation for his students. The work was almost all built by the master and his apprentices and is inspired entirely by the desert landscape, with low volumes framed by redwood beams and native materials such as rock, concrete mixed with local materials and desert sand. Today it is the home of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

Photo by Teemu008. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona 1937

Photo by Tatiana12. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hanna-Honeycomb House, Stanford, California 1937

The Hanna-Honeycomb House, named for its hexagonal plan and the first non-rectangular building Wright designed, was a simple, functional, and affordable middle-class design. The 1.5-acre lot included a guest house, hobby space, storage, double garage and garden shed. In keeping with the Usonian style, the homey, family-oriented aura of the horizontal volume building is provided by straightforward, natural materials such as wood and brick and by flexible, light-filled rooms with floor-to-ceiling windows that punctuate the elevations. Today the building is owned by Stanford University.

Photo by Teemu008. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hanna-Honeycomb House, Stanford, California 1937

Photo by Wallyg. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater (Kaufmann House), Mill Run, Pensylvania 1939

Wright said that “if you listen to the sound of Fallingwater you hear the stillness of the countryside”. And indeed, there is nothing more wonderfully intimate and pacifying than finding, nestled comfortably in the protection of a home retreat, the sounds of the forest. Nestled among the hills of Mill Run on the natural waterfall of Bear Run, the house with its disruptive cantilevered volumes clad in quarry stone is a passionate declaration of love by the designer to Nature and underlies a relentless search for a balance between Man, technology and landscape.

Photo by Orangejack. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater (Kaufmann House), Mill Run, Pennsylvania 1939

Photo by Kevinq2000. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Rosenbaum House, Florence, Alabama 1940

If one thinks of the Usonian architecture that depicted houses conceived specifically for the American middle class, small in size, simple but elegant and moderately priced, one cannot but remember Rosenbaum House, the only one designed by the master in Alabama and which embodies all the characteristics of this "style": "L" plan, single level, functional and flexible distribution, full-height windows, furniture incorporated into the structures and simple and natural materials such as wood and brick. After the death of the owners, it was purchased by the municipality of Florence and today houses a museum.

Photo by string_bass_dave. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Rosenbaum House, Florence, Alabama 1940

Photo by string_bass_dave. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Cedar Rock, Independence, Iowa 1950

Under the banner of gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), nothing was left to chance in this small house commissioned by a wealthy local family, from the design of the architecture to the furnishings and tableware (all designed by Wright). The building is a clear example of a single-level Usonian house, with flat roofs with projecting and protective pitches, an open and flexible floor plan, brick walls, wood window frames, full-height windows, and concrete floors. After the owner's death, the house was donated to the state of Iowa, which still retains ownership.

Photo by L.M. Bernhardt. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Cedar Rock, Independence, Iowa 1950

Photo by L.M. Bernhardt. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Kentuck Knob, Dunbar, Pennsylvania 1956

Designed at the ripe old age of 86 by the master, Kentuck Knob was one of the last houses Wright built. In the style of the Usonian, the single-story house with its vast cantilevered flat roofs of copper sheeting contrasting with the neutral tone of the natural stone of the walls, free-standing interiors finished in sandstone and North Carolina red cypress wood, the house has the peculiarity of a hexagonal plan but the usual recognizable grace in blending delicately into the natural landscape.

Photo by sarowen. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Kentuck Knob, Dunbar, Pennsylvania 1956

Photo by sarowen. Courtesy Creative Commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Muirhead Farmhouse, Kane County, Illinois, 1953

The house, the only farmhouse Wright ever designed, is in effect a ranch set on an 800-acre prairie, in the style of the Usonian lexicon that here employs squared volumes on a single level, generous flat roofs with massive brick walls, concrete finishes mixed with local materials and Tidewater red cypress. The building, which has undergone several renovations, is still owned by the family, which makes it visitable at certain times of the year.

Courtesy Creative Commons

Designed like a sharp-edged diamond amid subtropical woods, gentle hills, waterways, and wetlands, this single-family Wright villa has one of the most unique histories. Deeply intertwined with the architect’s life and his idea of organic architecture, the Hughes House represents a turning point that deserves to be told within the context of his residential poetics.

Designed by Wright at the age of 81, the house in southeast Jackson was built following the Usonian house model: a construction method and ethical principle Wright began experimenting with after World War II. The idea, in short, was to involve architecture in the reconstruction of the United States after the Great Depression by designing affordable homes for the American middle class. Low-cost, modular, and free of unnecessary ornamentation, Wright’s Usonian houses are numerous and still well-known—so much so that in 2022 a Seattle construction company revived their principles to build a new series of homes for the market. The Hughes House, however, stands out significantly from the others.

This forms a network—unofficial but increasingly significant—of ‘Wright house-museums’: private architectures that become collective heritage.

Nestled and almost buried among hills and cypress trees, the residence is built almost entirely of swamp cypress, a moisture-resistant wood typical of Mississippi’s floodplain forests. The exterior walls, as well as the floors, paneling, and custom furniture, feature the warm, pinkish grain of this wood, in an intense dialogue with the surrounding landscape. Its Y-shaped form traces the contours of the surrounding hills, in keeping with the principles of organic architecture.

The house is particularly famous for the fountain and pool at the back, designed together with the building, which function as part of a water path running through the garden and gave the house its nickname, “Fountainhead.” Viewed today, the Hughes House appears as the most dynamic and forward-looking iteration of Usonian houses—a model of American residence already looking toward the second half of the twentieth century, while remaining anchored in a millennial landscape.

The museum’s purchase is far from an isolated gesture: it is part of a strategy in which most U.S. cultural institutions are committed to preserving Wright’s legacy, particularly the Usonian houses, such as the Bachman–Wilson House, purchased, dismantled, and relocated to the grounds of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville.

This forms a network—unofficial but increasingly significant—of “Wright house-museums”: private architectures that become collective heritage.

A bulk sale of most of Wright’s properties also follows a certain renewed popularity of the Prairie House architect. Between unbuilt projects and iconic architectures, Wright is now everywhere, from TV series to trailer designs. And with this acquisition, he is also part of a museum collection in Mississippi.

Opening image: Courtesy Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy