It can be argued that no museum organization can boast among its venues such relevant buildings as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. In 1959, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York opens to the public, a significant evidence of a mature reflection on organic architecture by the American master of Modernism, who was then approaching the end of his career. Less than 40 years later, in 1997, Spanish king Juan Carlos I inaugurates with much fanfare the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao by Frank Gehry, a highly representative essay of the then rising season of parametric architecture. As of today, Wright’s and Gehry’s buildings are the foundation’s only permanent exhibit spaces, alongside the ancient Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, the unfinished behemoth along Venice’s Canal Grande, hosting the Peggy Guggenheim Collection since 1949.

The museum’s story begins in 1991, thanks to a political-urban insight. Confronted with the deep crisis that the port city of Bilbao was facing at the time, transforming it in just a few decades from the core of the regional economy to a rapidly decaying shrinking city, the Basque Country Autonomous Community establishes a partnership with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, and it invests several hundred million of euros in the realization of a huge exhibition venue, in order to display a part of its collections. A derelict site within the ancient port’s precinct is identified for the new building, for both symbolic and strategic reasons. The city is willing to be reborn from the same place that granted its wealth for several centuries; more practically, the flywheel effect activated by the investment of public money has better chances to reverberate on an urban context where several areas are in need of regeneration.

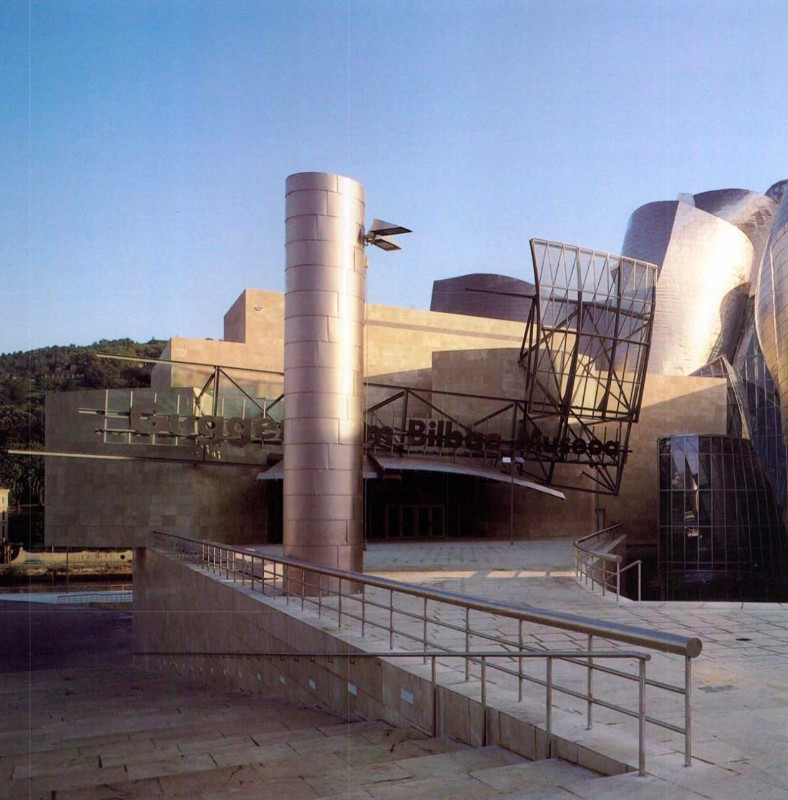

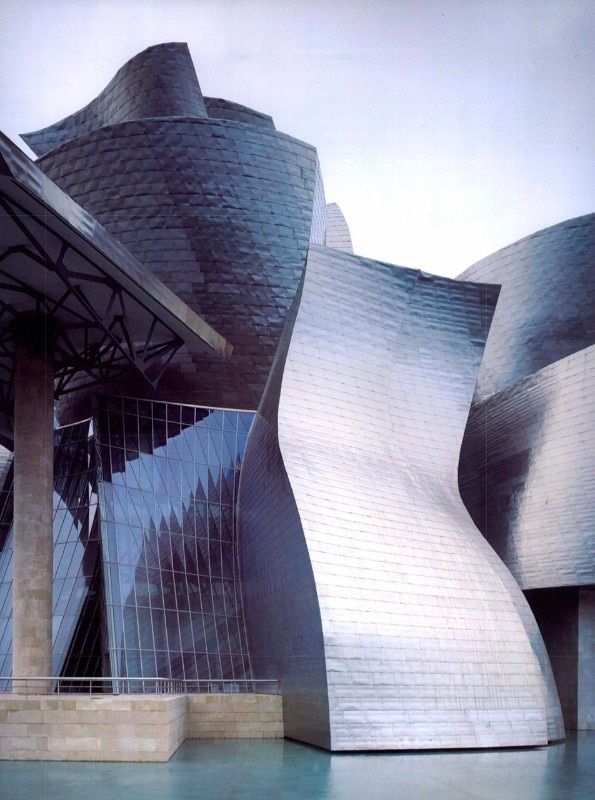

The commission is assigned directly to Gehry, who elaborates one of the best designs of his career, a building bound to make it into the histories of architecture for its capacity to combine formal research and spatial qualities. With its wavy, titanium clad façade, rising above a light stone podium, Gehry’s Guggenheim offers itself within Bilbao’s urban landscape as a flamboyant, shiny icon, a soon beloved symbol of the possibility of a new-found prosperity.

In parallel, regardless of the several streets and railway infrastructures that surround it, the museum can count on a system of public spaces of great urban significance. It opens up towards the regular grid of 19th century blocks with a large square, bypassing a section of the local ring-road. Through this platform, the historic city finds a new connection to the river, whose bank is reshaped as a public park and promenade.

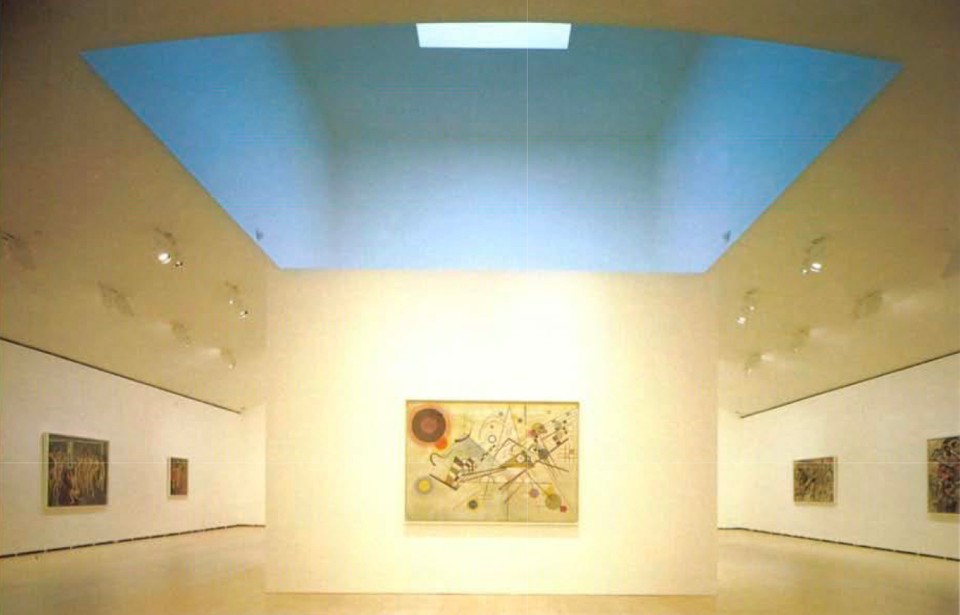

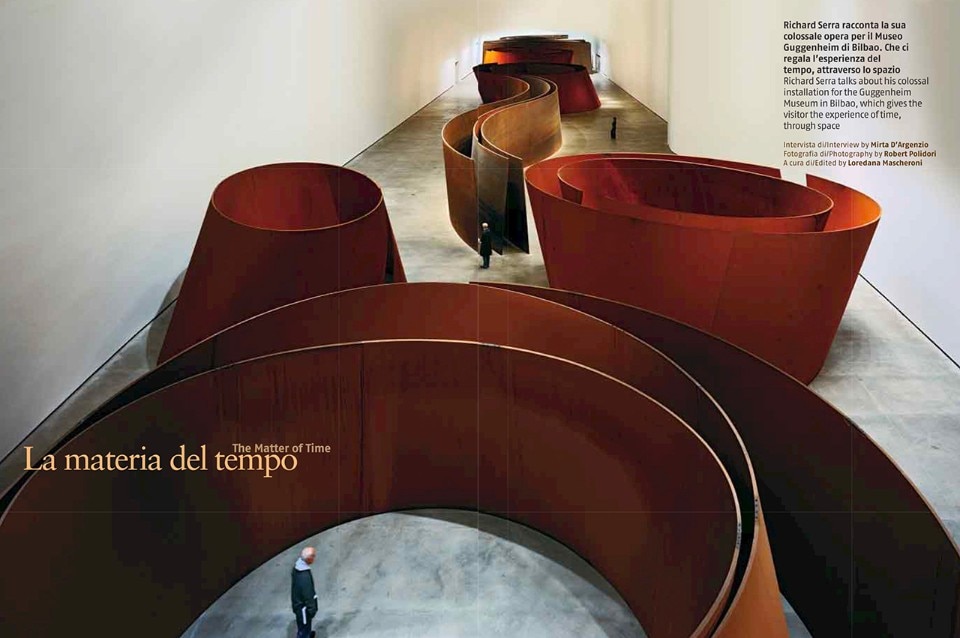

The museum broadens and diversifies the set of exhibit spaces available for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. The internal galleries add up to 11,000 square meters, a larger size than the Guggenheim Museum New York and Venice’s Peggy Guggenheim Collection put together. In addition to ten traditional, orthogonal "white boxes", filling the stone blocks, nine organically shaped rooms are enclosed within as many titanium petals. Several site-specific artworks have been commissioned over time for these spaces, as well as for the square, the promenade and the park, with the aim to reaffirm the openness of the institution towards the city.

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is often compared to the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, a project that Gehry started just before its Spanish counterpart, and that continues with great difficulty throughout the 1990s. The two buildings bear a clear formal resemblance not just because they have been conceived almost simultaneously, but mostly because they are both modeled through the Catia software. The latter establishes itself as the main tool for parametric design precisely following the success of Gehry’s experience.

Furthermore, if the opening of the Walt Disney Concert Hall activates a significant process of urban regeneration in the neighborhood of Downtown Los Angeles, the Guggenheim Museum succeeds in changing the trajectory of development of Bilbao’s metropolitan area as a whole. Within few years from its inauguration the Basque metropolis becomes the destination not just of massive tourist flows – as of 2019, the museum was visited every year by more than 1 million people – but of just as sizeable investments, for instance in the real estate market.

This phenomenon has become so intense that a neologism has been coined to define it. The term "Bilbao effect" has entered the current language of urbanism, to describe a model of urban regeneration through architecture that several cities have tried to replicate worldwide, and whose contradictory economic and socio-cultural outcomes are still much debated today.

- Project:

- Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

- Program:

- museum

- Location:

- Bilbao, Spain

- Completion:

- 1997