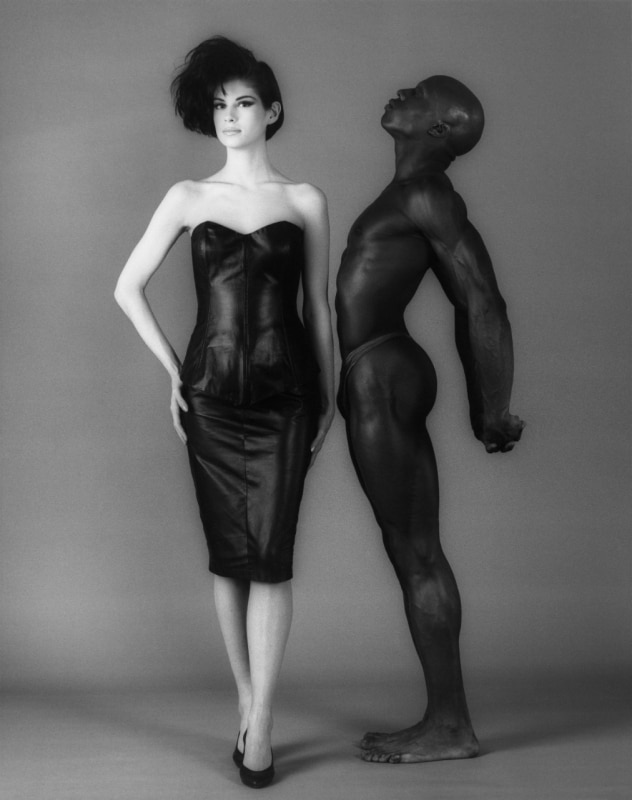

Germano Celant was the first to reinterpret Robert Mapplethorpe’s work, stripping it of the lurid patina that had branded his photography for years. In “Robert Mapplethorpe, tra antico e moderno. Un’antologia” (Turin, 2005), the art critic restores the image of an artist who, through statuesque faces and bodies, was able to portray America and its disillusionment, the inner unrest of those who fought against the ethnic prejudice and sexual conventions that characterized the United States in the postwar era.

The third of six children, resistant to the strict Catholic upbringing imposed by his family in Queens, Mapplethorpe was barely in his twenties when he gravitated toward the incredible melting pot of the Chelsea Hotel. In the beating heart of Manhattan, he settled permanently with Patti Smith, one of the most important women in his life. The community of intellectuals and artists — including Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin — that revolved around the Chelsea fueled the young Mapplethorpe’s curiosity. He fell in love with that avant-garde environment and chose to become an active part of it. He also frequented Andy Warhol’s legendary Factory, the personal studio of the father of Pop Art, destined to become a true cultural shrine.

Youth in New York and the discovery of photography

He grew up in 1960s New York, marked by intense political and cultural ferment but also by deep social inequalities that would culminate in the Stonewall riots on the night of June 27–28, 1969, marking the beginning of gay liberation movements in the United States. Mapplethorpe absorbed these rebellious and combative energies, increasingly aware that his tool for reading the world would be the camera lens.

My attitude in photographing a flower today is no different from photographing a penis. In the end they are the same thing.

Robert Mapplethorpe

A decisive turning point came with his meeting John McKendry, head of the Department of Prints and Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum, who opened the doors of the museum’s archive to him. A year later he met the collector and future lover Sam Wagstaff, who invested in his work by buying him a studio at 24 Bond Street and giving him a Hasselblad 500C.

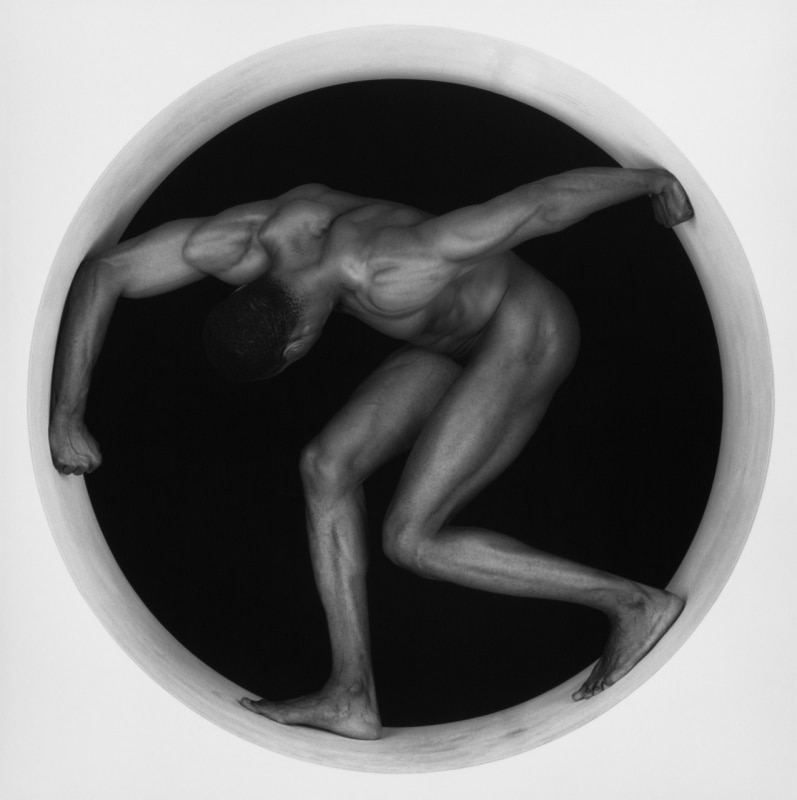

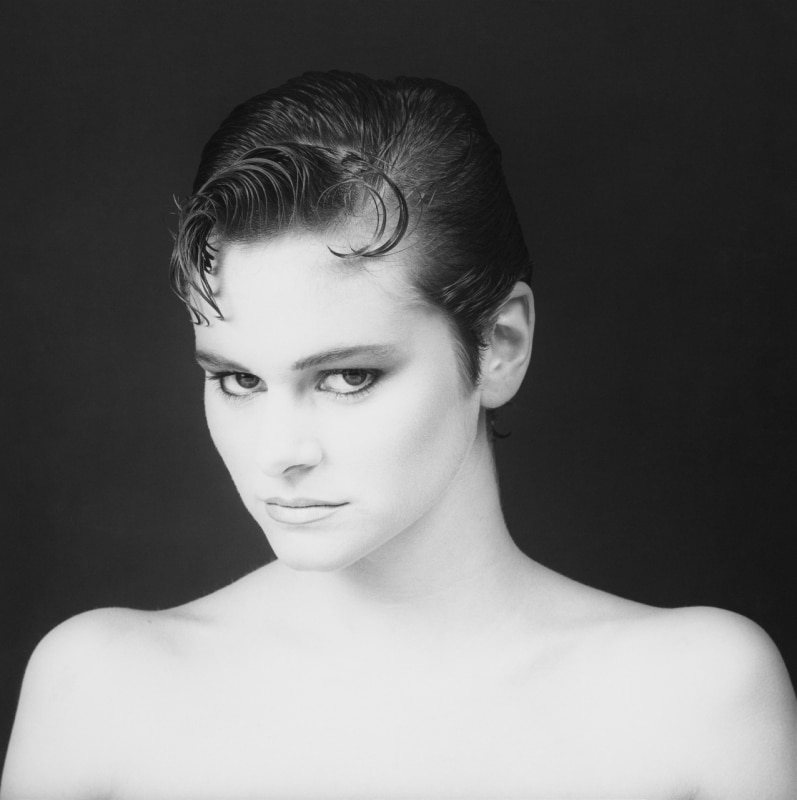

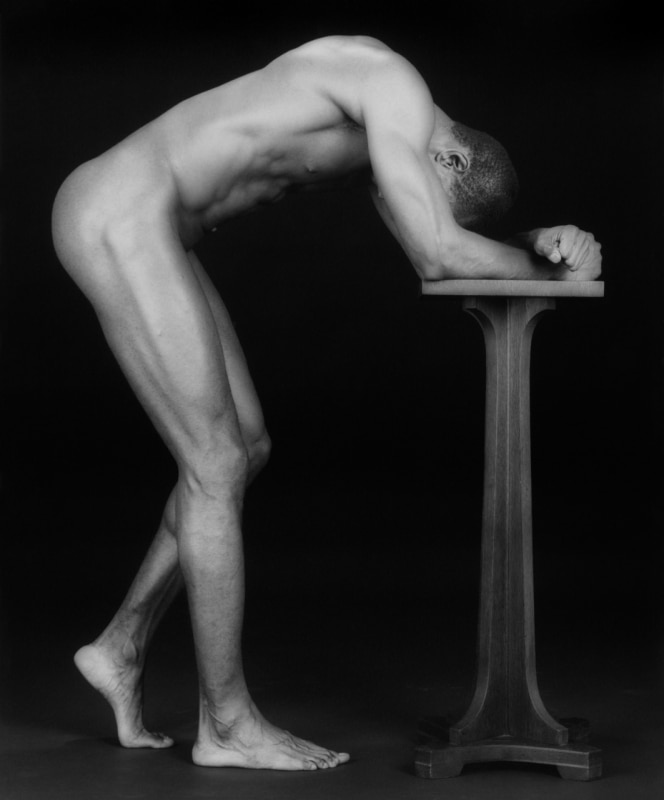

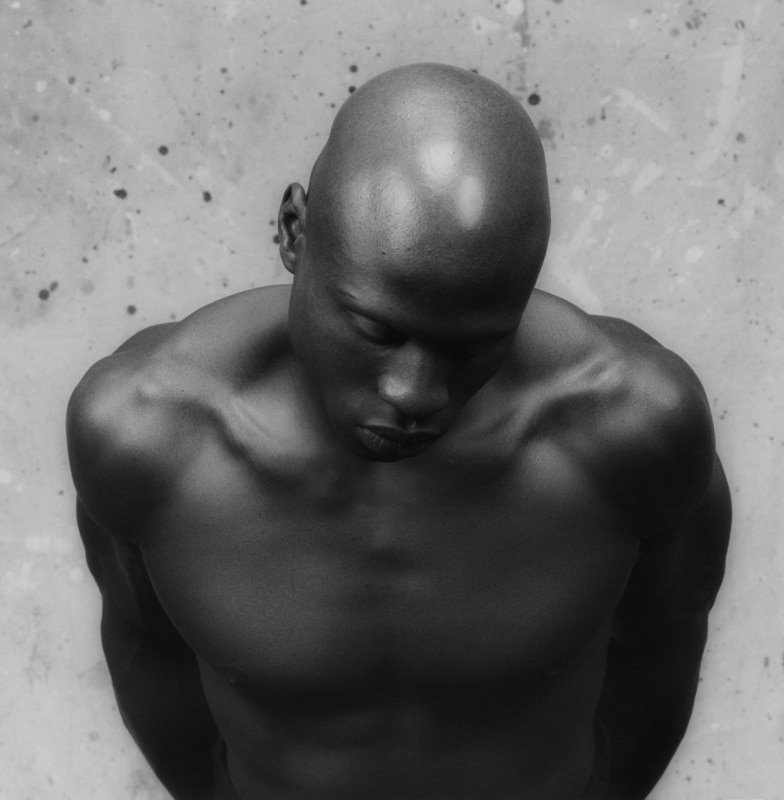

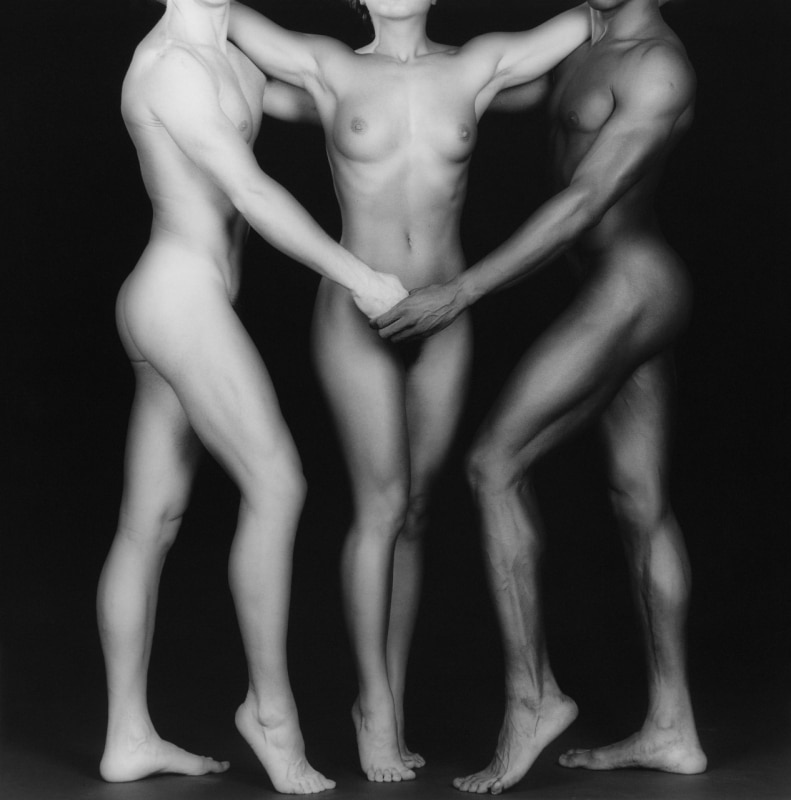

It was at this moment that Mapplethorpe was able to fully explore the new medium through subjects that, despite their aesthetic perfection and references to classical beauty, speak of fragility and imperfection. The honesty of his photography lies in his direct, unmediated intent to restore dignity to the surfaces he portrays, to the identities and stories they hold.

His gaze on sex and sensuality

There are forms of beauty that create distance and coldness, that call for separation. The beauty in Mapplethorpe’s photographs belongs to another realm: it is rooted in a sincere and forbidden sensuality that the artist experienced firsthand, having grown up in a family permeated by a deep sense of guilt surrounding sex.

As he told Germano Celant, “Pornography influenced me, but only in terms of subject, because my attitude in photographing a flower today is no different from photographing a penis. In the end they are the same thing” (Robert Mapplethorpe. La ninfa fotografia, Skira Ed., 2014).

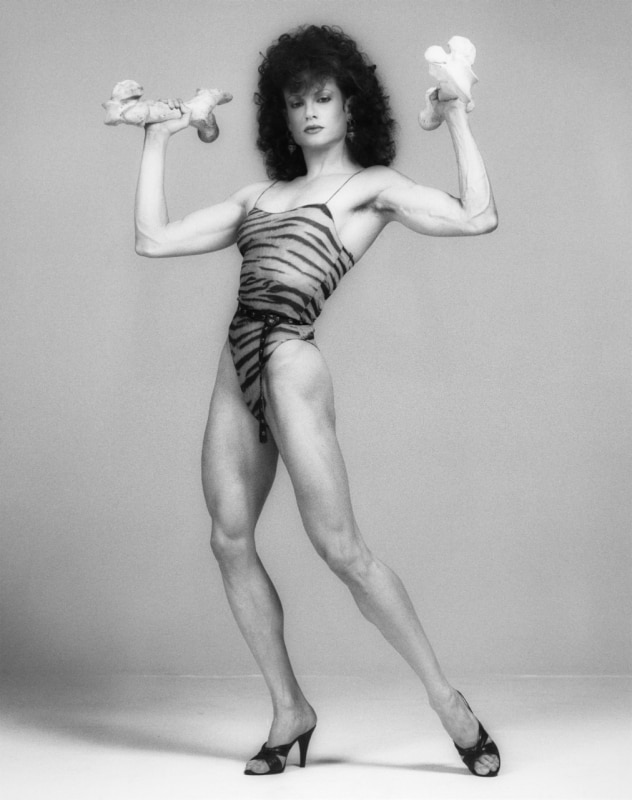

The smooth, clean surfaces, similar to glossy paper, do not distinguish a buttock from a petal, flesh from cellulose. Everything is linear or perfectly contracted, everything observed with a hungry curiosity that investigates, with the same intensity, a centimeter of skin and the pistil of a flower.

An artist who, through statuesque faces and bodies, was able to portray America and its disillusionment.

Germano Celant

He portrayed Patti Smith, musician Derrick Cross, bodybuilder Lisa Lyon, and himself, again and again. As he looks into the lens with a raised eyebrow and a lit cigarette, he presents himself to his audience as both artist and subject, flowing from one identity to another without too many explanations.

The first AIDS deaths

It was the 1980s when the first deaths caused by HIV shocked public opinion. Year after year, the artist watched more and more friends and colleagues disappear, destroyed by the virus — first among them Wagstaff himself, who died of pneumonia.

His own AIDS diagnosis came in 1989, and in his final years the photographer decided to direct all his efforts and energy toward the illness that was slowly making him disappear: in 1988 he founded the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, a charitable organization to fund AIDS research and support photography at an institutional level. That same year, the master of black and white had his first major retrospective in an American museum, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

In the exhibition at Palazzo Reale in Milan, curated by Denis Curti, the aim is to pay tribute to the aesthetic research of an artist capable of narrating crisis and fragility through formally impeccable images and ultra-clear surfaces. Ultimately, it is precisely this tension between strength and vulnerability, vigor and weakness, that distinguishes a perfect, motionless Greek statue from a — always imperfect — human being.

Opening image: Patti Smith, 1986 © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission

- Show:

- Robert Mapplethorpe. The forms of desire

- Edited by:

- Denis Curti

- Where:

- Palazzo Reale, Piazza del Duomo 12, Milan

- Dates:

- January 29-May 17, 2026