Over the course of four months, Georgian artist Tolia Astakhishvili has transformed a 15th-century Venetian house — now home to the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation — into a total artwork. The result is hauntingly powerful.

Just a stone’s throw from the Ponte dei Pugni, a relic of chaotic Venetian street boxing banned in 1705, there’s a door that looks entirely anonymous. Behind it lies a world of its own: the world of Tolia Astakhishvili, who lived and worked here from January to May, radically reworking every corner. Think of it as an artist’s extreme makeover, applied to a building that’s been reshaped many times before: confiscated by Napoleon from the nuns of the Sant’Agnese priory, later bought by painter Ettore Tito, then redesigned in the early 20th century by Angelo Scatolin with a slightly stylized modernism, raised by a floor, and eventually split into two units — a duplex apartment and a set of medical offices — under the Cassa Marittima Adriatica.

Giorgio Mastinu, who closely followed the entire transformation, shares this story with Domus. Today, the building is the Venetian home of the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation. Not your typical palazzo, like Kapoor’s, but a house marked by time, upheaval, and constant reinterpretation.

‘To love and devour’ is unlike anything you’ve seen lately: an artwork, yes, but also a love letter to what a house can be — mine, yours, a family home, a lost one.

And it’s here that Astakhishvili carried out what turned into a deep excavation of the building’s soul. She gutted, carved, reshaped, repositioned, demolished, and rebuilt. “At first the builders didn’t understand, then they became a core part of the project,” Mastinu explains, showing photos on his phone of a wall being carefully demolished — a heuristic process more than a renovation. Much of the work aimed to recover Scatolin’s original vision: Mastinu points to old blueprints, part of a vast body of research. For instance, the visual axis from the entrance to the courtyard was restored. A tiny service bathroom, added later, was sliced in half — only the lower portion remains, like something cut off at the knees. Upstairs, the bathroom walls are gone but the pipes remain, revealed by hammer and chisel, running like a metallic root system around the adjacent living room (“the inner life of water systems,” the artist says). There are drawings. So many drawings. “That is the start of art,” says curator Hans Ulrich Obrist in his distinct Swiss-German accent. He’s also the president of the jury for this year’s Architecture Biennale, which opened in parallel. Dressed in his signature cap, black suit, and large glasses, he explains the project while filming Astakhishvili on his iPhone as they speak.

Alongside the drawings is a large painting, in a room upstairs (they call it “the green room”), and downstairs you enter a space with windows covered in newspaper. Turn a corner, and you find one of the two films included in the show. Just behind it: a niche. The house is full of them, and each hides a surprise. Or better: surprises are everywhere. Astakhishvili moved boilers and toilets, turned bits of wiring and the metal veins of a heat pump into sculptural fragments. She scattered photos and artworks throughout. She shattered the space with mirrors. She reconnected the residential part of the house with what had once been the offices — two identities that had diverged over time but now unfold fluidly, side by side, in a house that’s large, but not enormous. One where you might easily lose your bearings, as if you’d fallen into House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski.

It holds shivers and shadows, emotion and light. Birth and death. Destruction and reconstruction. Detail and memory. The shape of time and of design, the idea and its execution. Everything that makes a house the house.

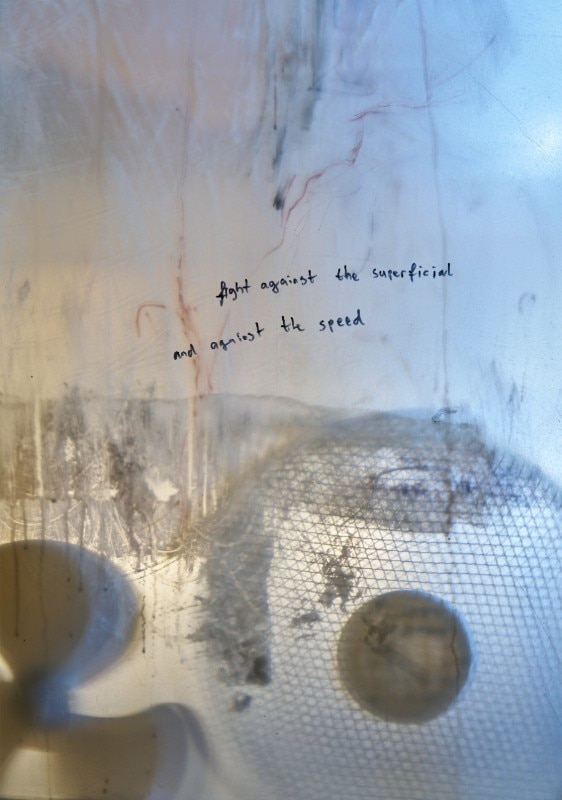

“Like a child whose parts you can’t separate from the mother’s,” says Astakhishvili, describing this house-show — or maybe house-sculpture — which she sees as a single, all-encompassing artwork. The title, “to love and devour”, says it all. There are dozens of handwritten phrases scattered across the walls. But right beside the heavy stair railing (“we thought about removing it,” says Mastinu, “then we decided to keep it”), you’ll also find notches and dates — the growth marks of a child who really did grow up here. “Fight against the superficial and against the speed,” the artist has written on an upstairs wall. Perhaps a message from the future, addressed to that very child. In this house, past, present, and future truly coexist. It’s a child travelling through time.

Within this sculpture-house-child, you’ll also find a false wall previously shown at the Macro, now installed again. Works by other artists, too — many of them. “A very special way to relate to other people’s art,” says Astakhishvili. There’s a huge table with cutlery sunken into plasterboard like fossils — the proverbial “elephant in the room” (as Mastinu calls it), impossible to miss. Roots have pierced through the walls and surfaced on the interiors. Salt blooms on the plaster, as it does across half of Venice. There are small things and large things. There’s a soft light downstairs that fades quickly with sunset, and upstairs, everything is luminous: sunlight filters through filigreed windows, drawing lace-like shadows on the tiles. There’s even a pillar that recalls a pair once removed during earlier renovations. But above all, there’s the soul of a house that has been touched, revealed, redesigned, seduced, stripped with power tools and chisels, and finally rebuilt — not to restore some past ideal, but to reconnect it with what it was, and could still become.

“To love and devour” is unlike anything you’ve seen lately: an artwork, yes, but also a love letter to what a house can be — mine, yours, a family home, a lost one. Astakhishvili speaks of it in a book-length conversation with Obrist that accompanies the show. It holds shivers and shadows, emotion and light. Birth and death. Destruction and reconstruction. Detail and memory. The shape of time and of design, the idea and its execution. Everything that makes a house the house.

The show runs through November — and if you’re heading to the Biennale, a detour to Dorsoduro is not optional.

Opening image: Tolia Astakhishvili, forbidden place, 2025