On the afternoon of 9 March, the maternity and gynecology ward of the Mariupol children’s hospital in Ukraine was bombed. The following day, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov spoke about the bombing of the hospital during a press conference after talking with Ukrainian Minister Kuleba, stating that “the hospital was Azov Battalion’s base (the extremist Ukrainian military unit)” and that “those civilians were used as human shields”. An absurd atrocity and a foolish declaration by Russia, which has also been denied by the numerous images circulating. A true Massacre of the Innocents that finds no explanation.

The photo of the Mariupol Children’s Hospital by Evengy Maloletka, a Ukrainian freelance photojournalist based in Kiev, Ukraine. The image was published on: The Guardian, ABC News, CNN, Sky News.

In the Gospel of Matthew (2:1-16), Herod the Great, king of Judea, ordered the massacre of all the children in order to kill Jesus. The messiah escaped the massacre thanks to the help of an angel who warned his father Joseph in a dream and ordered him to flee to Egypt. This Gospel story is known as the episode of the Massacre of the Innocents and there are many analogies with the present day.

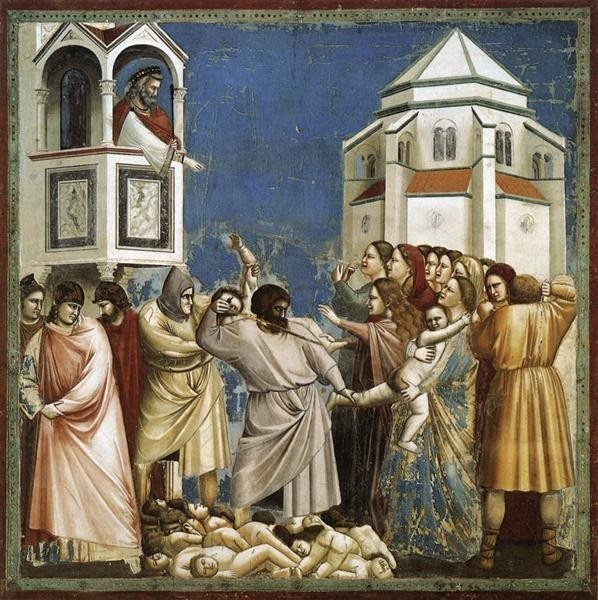

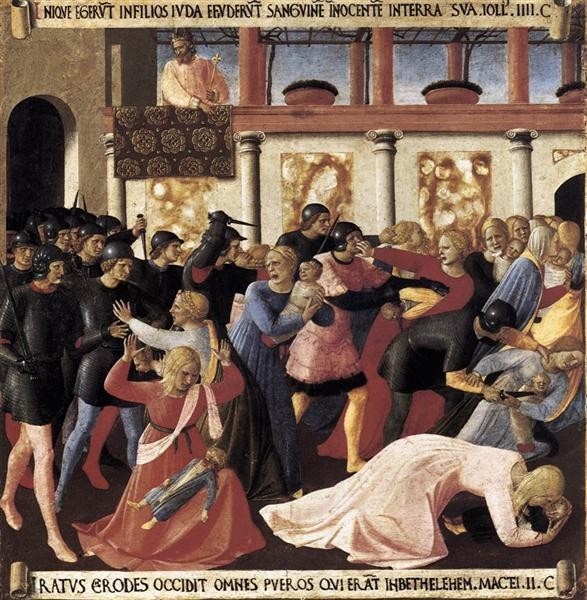

Many works narrate the biblical massacre: Duccio di Buoninsegna, Gentile da Fabriano, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Fra Angelico, Tintoretto, Peter Paul Rubens and many others. Once again, art presents itself as an attentive and far-sighted chronicler.

“Here nothing, but most horrid heaps remain/ Of Fragments rais’d by rage, and curs’d design/Nothing but bloudy Piles, and limbs, that are/ Lopp’d off, and scatter’d, as in fields of War”: This is how Giambattista Marino describes the scene in his 1632 epic poem entitled The Massacre of the Innocents – and Guido Reni interpreted it in a similarly strong manner. A canvas almost three metres high immortalises the bloodiest scene, the terrible massacre of the children of Bethlehem.

The episode takes place entirely in the foreground, where all the characters are. In the middle, two killer soldiers are attacking five mothers ready to fight back, while the children react in different ways. On the ground there are two tiny corpses, one facing the front while the other is resting on the first. On the ground, blood.

A scene full of sorrow, with classical architecture in the background and two angels at the top handing mothers and children the palm of martyrdom.

Reni succeeds in summing up feelings and technique in a work that represents the artist’s highest classicism, with the bodies looking very much like statues. Regular physiognomies, elegant postures and volumetric draperies make the little space in which Reni designed the scene complete. In that space, he concentrates all the pain and action of the characters. Everything is fast and in extreme balance through a pyramidal composition intersecting at the centre. The trajectories of the bodies emerge from the painting and continue, like a photographic snapshot, beyond the canvas.

“A voice is heard in Ramah, mourning and great weeping, Rachel weeping for her children and refusing to be comforted, because they are no more”: Matthew the Evangelist sums up the sentimental tragedy in this sentence, which we could use as a perfect description of this time.