“No, painting is not made to decorate apartments. It’s an offensive and defensive weapon against the enemy.” Pablo Picasso was right. Helpless and incredulous, we continue to experience moments of concern and dismay. How this is possible is still unclear to us. War. Innocent victims of unknown or unclear interests. Victims of lies and madness, of wrongful and undemocratic policies based on economic interests and a lust for power.

In this case, art serves as a manifesto of past horrors, as well as an emblem of what is happening and will happen. Every day, in the newspapers, we see distressing images of destroyed cities, injured civilians and, unfortunately, dead people. Too many dead people.

Philip Guston, a contemporary American artist, painted an extremely powerful work of art – Bombardment. The painting, which was made in 1937, takes a circular tondo form. During the Renaissance, many paintings had this same shape, especially when it came to paintings depicting religious scenes. The tondo referred to the idea of perfection, giving the work itself an idea of absolute magnificence.

Guston, on the other hand, overturns the ancient idea of the tondo and uses it as a technical and, above all, emotional ploy. Squeezed and wrapped up in the whirlwind of violence, the bodies are sucked in without a way out, caught up in the violence of the fate that has befallen them. The planes determine the direction of the narration, and in the exact centre of the painting, we see the explosion of the bomb that upsets everything. The story is extremely orderly despite the madness it represents. Guston finds a place for every little detail with an almost mad lucidity, and in these details, he merges time and dimension, loudly declaring the absurd madness of that event.

The mask worn by the man on the right particularly strikes us, but the most interesting figure, recalling more ancient paintings, is the mother with the child at the top left. This contemporary Madonna is holding a naked child in her arms as if he were a new baby Jesus. The reference is strong and powerful, and above all, it seems to be included not to bless, as it was done in the past, but to curse the attack. The mother is looking at the planes, but her body is fleeing. Cold colours emphasise the cruelty and the volumetric shapes of the bodies amplify the message.

Art as denunciation, painting as an instrument of defense that exposes the executioners and aggressors to the world. Actuality that generates art. Inspiration in a certain way. There are also pictures of this war that resemble works of art. One recent picture has struck the interest of the many reporters who are reporting on this moment, namely the statue of Jesus Christ being moved from a cathedral in Lviv to a bunker in order to protect it.

The photo, taken by André Luis Alves, a Portuguese freelancer, captures the statues being “evacuated” from the cathedral. This is not the first time this has happened – the sculpture had already been taken away during the Second World War. In the San Marco Museum in Florence, there is another extraordinary work: Beato Angelico’s Deposition from the Cross. It is the same scene, the same power, the same pain and a court of people supporting the body of Christ. At the top, a man holds the body by the arm, just like in the photo. On the right, another figure occupies the scene while at his feet, others are mourning. In the photo, exactly as in the photo.

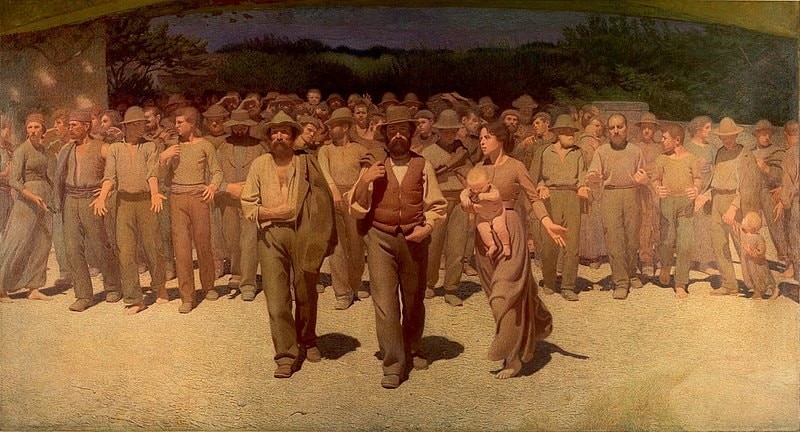

Daniel Leal, journalist and photographer for the French press, captures another scene and reminds us of yet another work of art. A group of women holding their children by their hands is fleeing. We immediately think of Pellizza da Volpedo and his well-known The Fourth Estate. The idea was always the same: the search for freedom and justice.

This is the power of art, the one that anticipates and announces, that manifests and explains. A warning for the new generations, hoping that it will be increasingly taken into account.