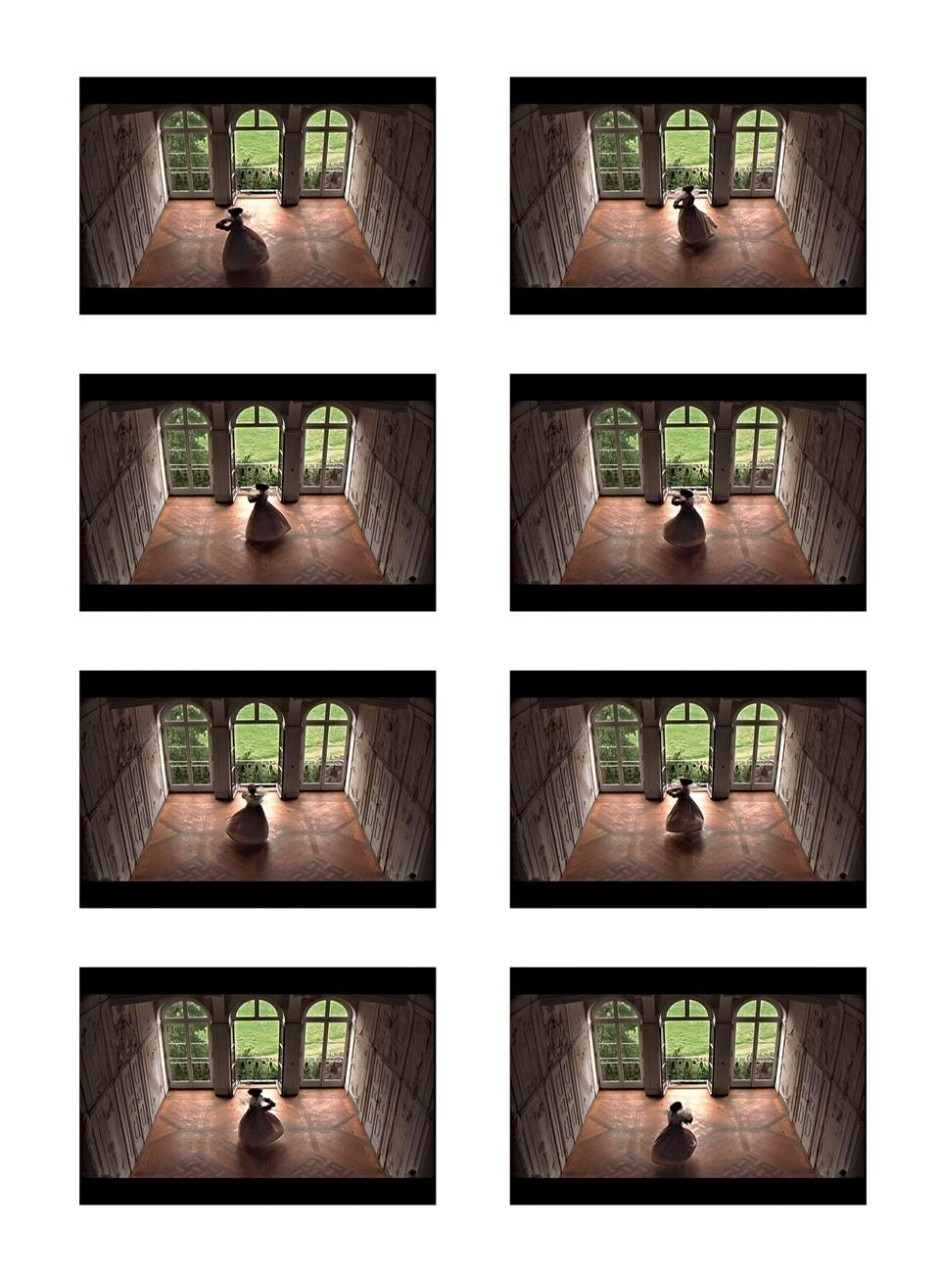

Once Upon A Time is also the title of an exhibition on at the Deutsche Guggenheim Museum in Berlin until 9 October. Curated by Joan Young, it focuses on the fairytale and fantastic content of video artworks of the late 20th and early 21st century. The exhibition features six video works selected from the Guggenheim collection to highlight the common approach adopted by internationally renowned artists (Francis Alÿs, Cao Fei, Pierre Huyghe, Aleksandra Mir, Mika Rottenberg and Janaina Tschäpe) when narrating the contemporary world—that of creating a myth or writing a fairytale.

The real fairytales, this observation seems to be saying, are the fake ones. However much we seek it out, the fantastic only exists in real life to the degree that we ourselves put it there.

Vincenzo Latronico