The Theater is not a place. It is a function. We often assume it to be concrete, velvet, a wave of hidden beams, a static diagram. In this misconception lies its deepest, unresolved truth. If architecture is the stubborn will to endure, the quintessential artifact designed to defy the erosion of time, then Theater is its perfect and sublime contradiction.

Every curtain is ultimately a hypothesis, a veil lifted not to reveal something new, but to expose the stark structure of absence. The stage is the only place in the world where the object of devotion, namely emotion, catharsis and narrative, appears to dissolve an instant after the final applause.

The Theater is not a place but a function: a building whose sole purpose is the ephemeral experience — an accelerator of time that renders the intangible dramatically real.

Its facade remains, but the resonance of the performance vanishes, only to recur. This is its unassailable, radically modern construction philosophy: a building whose sole purpose is the ephemeral experience — a majestic and necessary container that exists only for the fleeting moment in which it is filled with vibrating bodies and disappearing voices. It is not a monument. It is an accelerator of time, a device that renders the intangible dramatically real.

The permanence of theater in visual art lies in its stage, which, beyond being architecture, is an iconographic motif. It represents a powerful metaphor for the existential condition that has long haunted the eyes of the great masters.

Beginning with architecture itself, this narrative opens a dialogue with the ‘painted theater,’ which for centuries has mirrored and interpreted the essence of our humanity. The journey starts in the seventeenth century with the work of Antoine Watteau, master of melancholic grace and fêtes galantes. Take a close, attentive look at his Pierrot, also known as Gilles (c. 1718–1719, Musée du Louvre).

The subject, portrayed full-length and isolated, clad in luminous silk, stands still, almost monolithic. Pierrot stands as the silent focal point of the composition, even though, narratively, he remains detached from the bustling ensemble of commedia dell’arte characters gathered below. Gilles faces the viewer frontally, a pose that underscores both his hieratic presence and his estrangement. Through layers of transparent glazes and subtle modulations of color, Watteau does not depict theatrical bustle but suspension — the performer’s inherent solitude, the mask irrevocably merging with the man beneath.

The clown’s melancholy, exposed to view yet emotionally unreachable, reveals theater as a place of ephemeral magnificence and deep existential alienation.

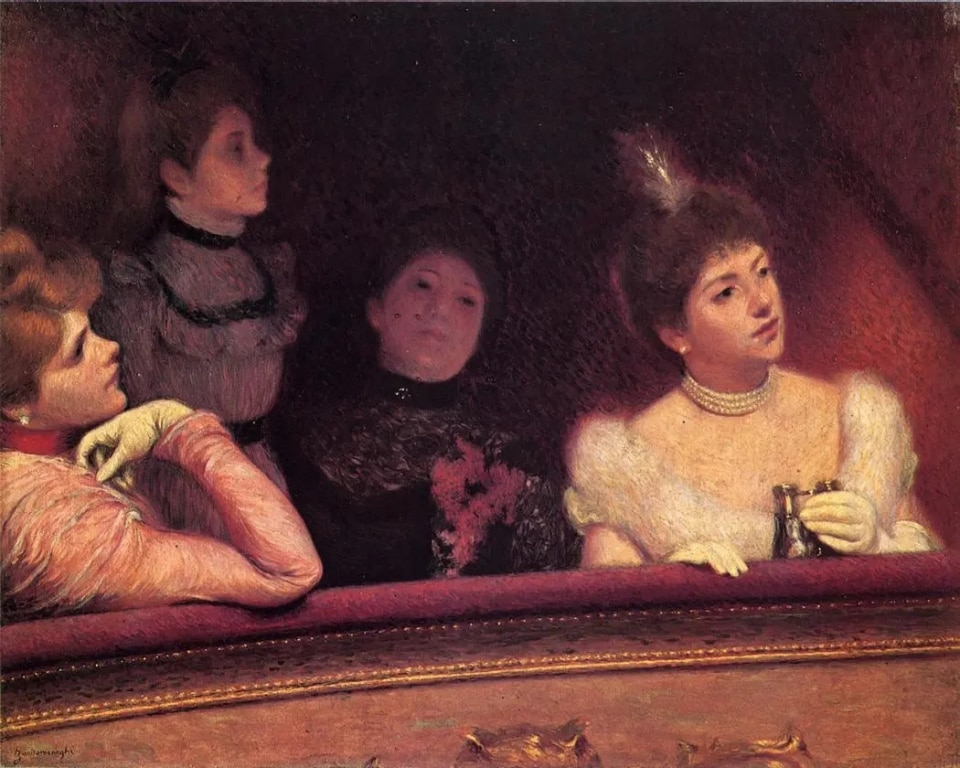

Moving forward to the latter half of the nineteenth century, we enter an age when the stalls and private boxes had become arenas of social display. In this context, we engage with artists working in dialogue with Impressionism. One notable example is Federico Zandomeneghi, who was active primarily in Paris. His At the Theatre (c. 1885–1895) enacts a radical shift. The focus moves from stage to audience—or rather, to the private box, the mirror of the demi-monde. The elegantly dressed women emerge in warm, artificial light that models their figures through vibrant strokes. They are protagonists not of the drama unfolding below, but of the act of being seen and seeing. Theater becomes an elevated salon, a site where representation unfolds both onstage and among the spectators themselves. Zandomeneghi captures velvet atmospheres, hushed murmurs, subtle vanity, and social hierarchy. Theater here exalts not only dramatic art, but the social ritual and dialectics of the gaze that structure the theatrical experience.

Every curtain is a hypothesis: a veil lifted not to reveal something new, but to expose the stark structure of absence.

Crossing the ocean into the American twentieth century, we turn to the severe realism of Edward Hopper. His work offers a visual synthesis of metropolitan solitude. The Sheridan Theatre does not depict the performance itself, but the intermission — or, more often, the empty theater afterward. The theaters painted by Hopper are sparse or nearly empty, populated by scattered figures who appear detached. Architectural lines are austere, almost abstract in their rigidity; warm, artificial lights expose their bare structure. In Hopper’s eyes, the theater is not a hearth of passion but a space of transit — or, in darker terms, a container of solitudes. Desolation asserts itself even in a place designed for crowds.

Ut pictura poesis. The true architecture of vision — the framework supporting the structure of Western art — is not a dialogue between painting and poetry, but a conflict, physical and spatial. Intellectual honesty demands a return to fundamentals, to Plato and Aristotle: the operating system of art is not description, but mimesis. What is its ultimate aim? The simulacrum: the construction of human action that seeks not beauty, but a cathartic effect. Theater and image share the same cultural infrastructure.

When Jacques-Louis David unveiled his canvases at the late-eighteenth-century Salons, he was not offering ‘paintings.’ He was offering shock. The anguish of Andromache, the bodies of Brutus’s sons, the misery of Belisarius — this was not painting; it was performance. The public did not merely look; it was onstage, swept up in a merciless mise-en-scène.

Theater testifies to the vitality of the human spirit and intellect, from Aeschylus to the present day. It is not merely architecture — it is culture inhabiting its own walls.

Opening image: Edward Hopper, Sheridan Theatre, 1937, Newark Museum of Art, Newark. Courtesy Wikiart