“He was one of the great Italians “against” photography’s protagonists: against injustice, against social inequalities, against racism, against wars, against white deaths at work, against asylums alongside Basaglia, against the occupation of Saharawi people’s lands.” This is how Gigliola Foschi, curator and photography expert, describes Gian Butturini (1935-2006). And it is important to start from here, because the photographer has recently been the subject of a virulent, unpredictable but significant attack.

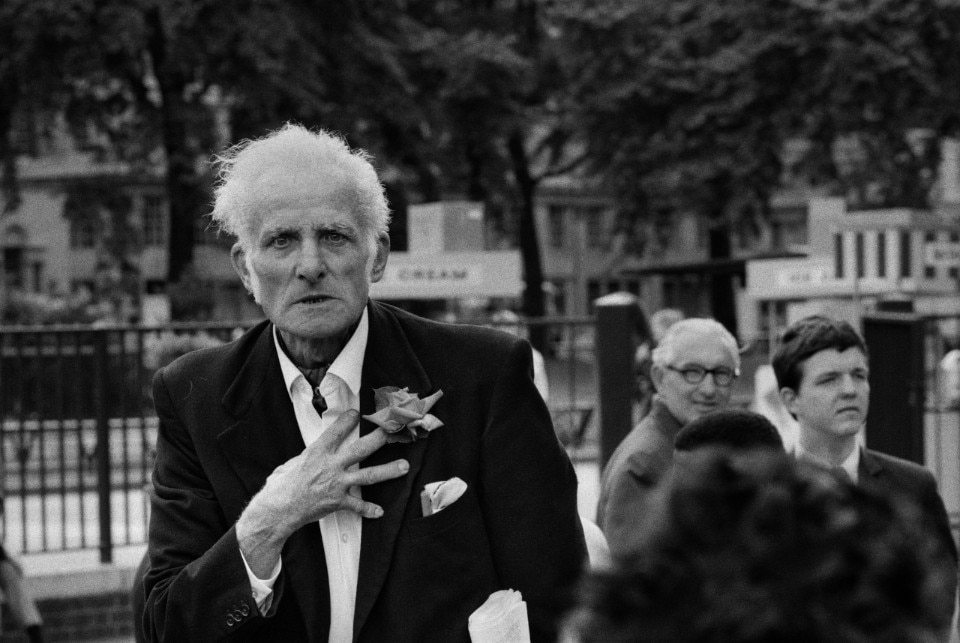

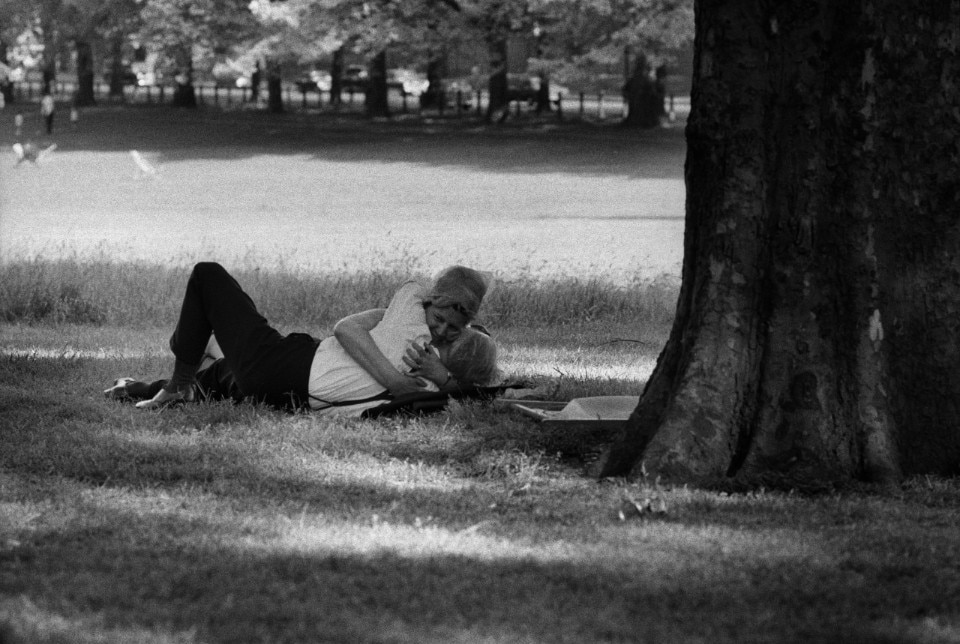

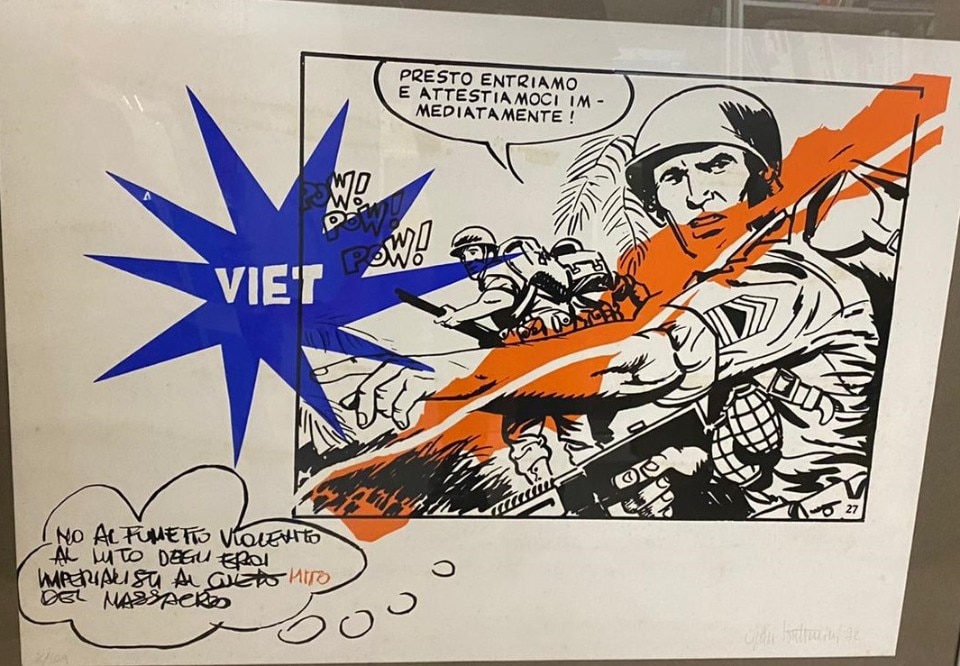

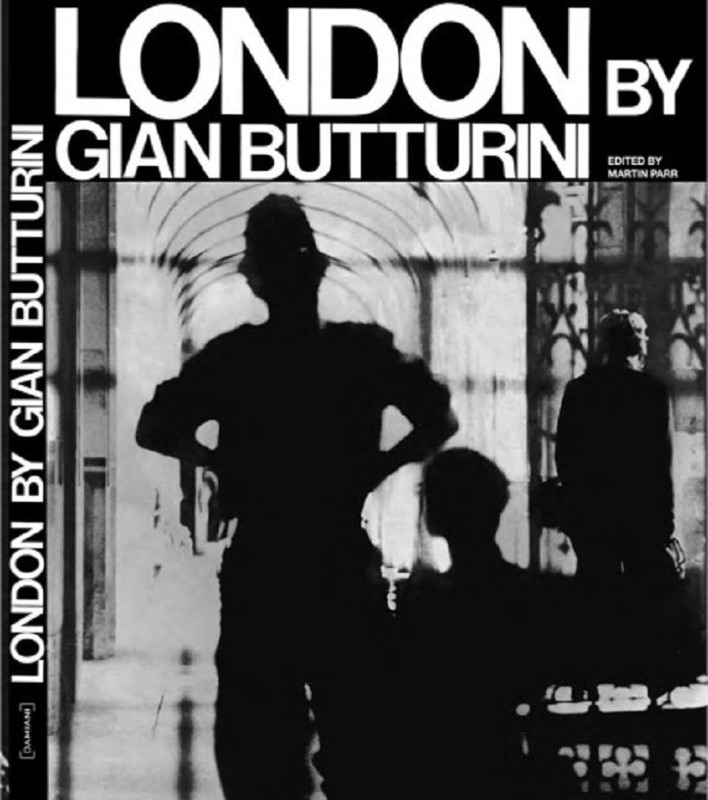

The attack concerned a diptych that appeared in a 1969 photographic book London, republished in 2017. London is the first of his books: at the end of the 1960s, after years working as a graphic and advertising designer, Butturini chose to change his life. This was legitimised by a trip to London to explore the city, focusing on its inhabitants: women, men, children, all-aged couples flirting, young people demonstrating against the Vietnam’s war, others brutalized by heroin, hippies portrayed as prophets of a new, fairer society; homeless people in bad shape, forced to move around carrying what they owned, but endowed with the ancient philosophers’ dignity. Apparently nice children who are surprising because a closer look at the blazer reveals the presence of a small pin with a hooked cross.

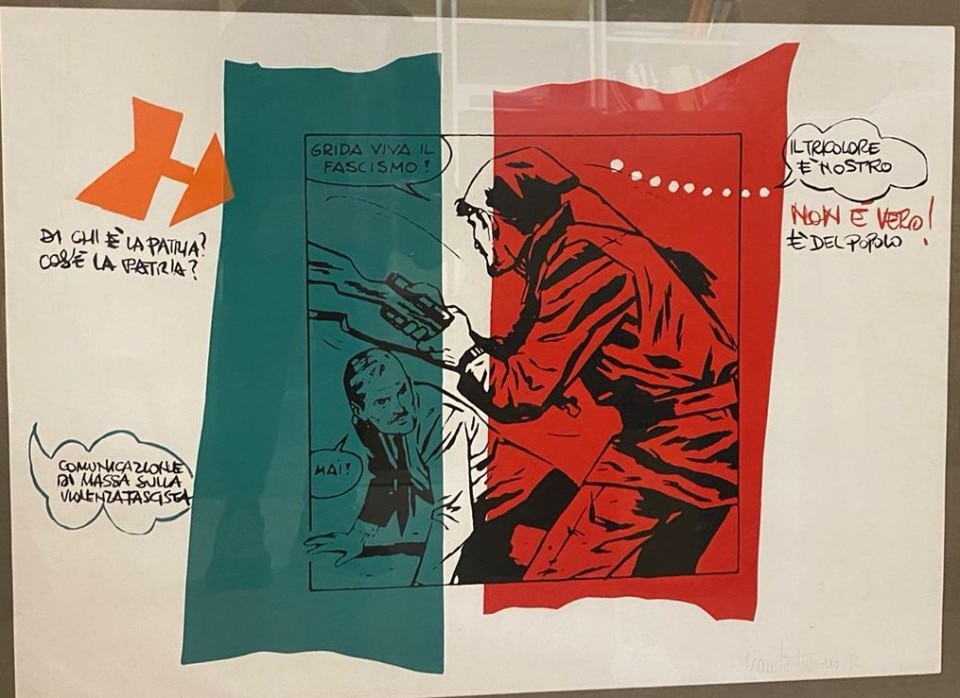

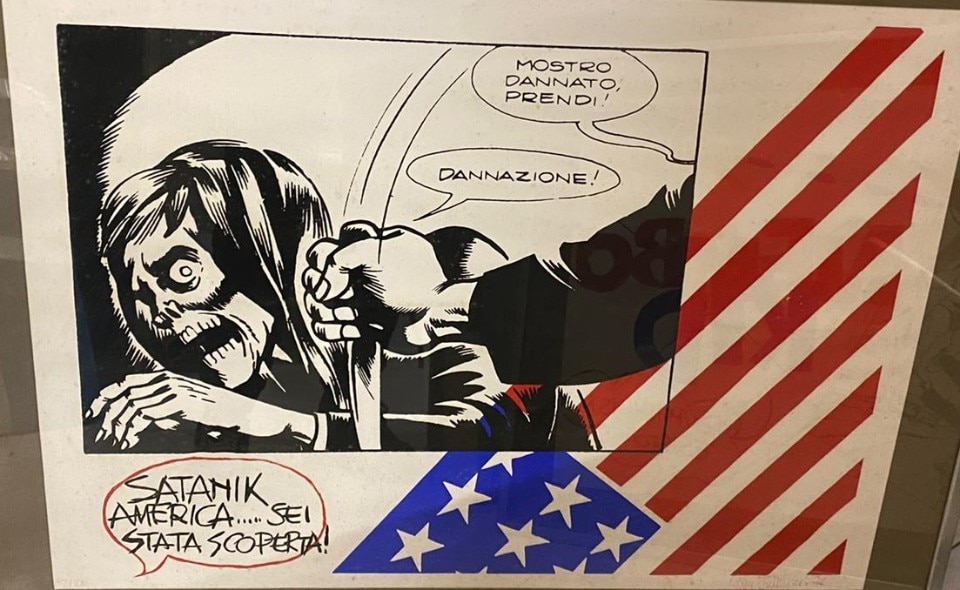

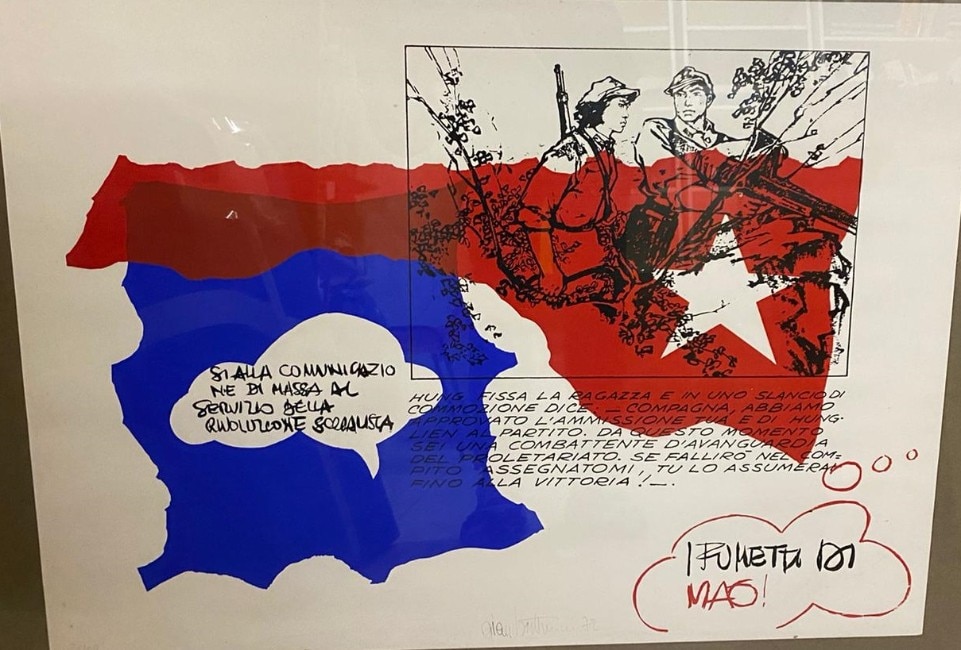

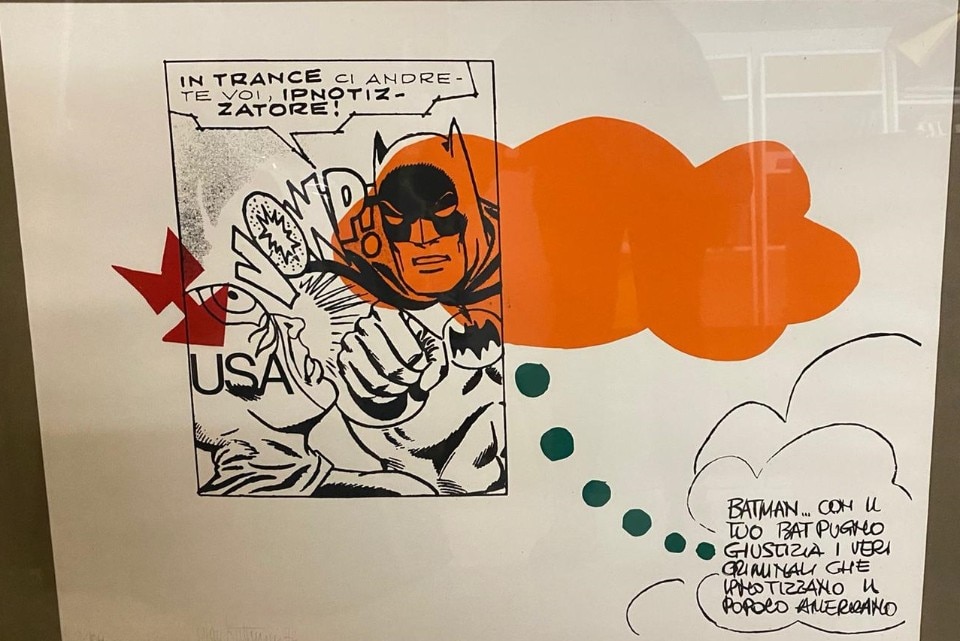

In the book, documentary research and graphic re-elaboration are combined for expressive purposes; the images are variously treated: sharped or grainy, close-ups and overall views, cropped, combined, alternated with graphic signs or texts, including the poem Europe! Europe! by Allen Ginsberg, on the dehumanisation of life in the metropolis. In terms of language, the book is thus in line with the most advanced experiments of the period and shows the awareness that radical intentions must correspond to new formal solutions. While the narrative, which is perfectly coherent, reflects the tension of the moment and the author’s political and social awareness, his closeness to the liberation and protest movements, his desire to do in-depth counter-information, his affinity with the Beat Generation’s ideas. If this was not enough, his position and the criteria for his choice are clarified in the two short, very clear pages he wrote himself as an introduction.

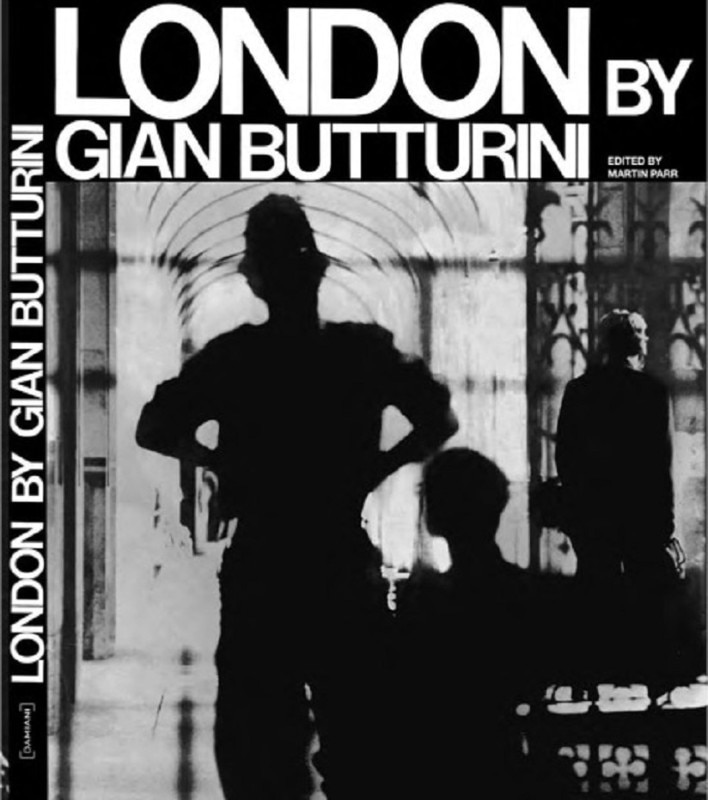

Martin Parr considers the book exemplary and in 2017, almost 50 years after its first publication, after having included Butturini in exhibitions and photo books, he decided to reprint it, entrusting it to Damiani, an Italian publishing house.

However, the unexpected happened. A British student, Mercedes Baptiste Halliday, finds offensive the juxtaposition of two photos in Butturini’s book: one of an Afro-British ticket-taker, exhausted by existence, who he photographed from the glass cage of the underground; and the other of an icon of the time, the London zoo’s gorilla Guy Fawkes; the author sees it as a symbol of Britain’s proud post-colonial character. All the more so since the name Guy Fawkes constitutes a warning to anyone who might harbour subversive thoughts: Fawkes is in fact the Catholic militant who in the 1600s, as part of the failed Gunpowder Plot, had attempted to kill the sovereign. The animal, that, as Butturini writes in the book’s introduction, “receives with imperial dignity on his frowning muzzle the jokes and zingers thrown at him by his nephews in ties”, had arrived at the zoo in the 1940s, at the age of one year, and was destined to spend the rest of his life in a cage.

Social cages and material ones, both instruments of mortification and segregation, are therefore the explanation of the diptych.

Butturini himself must have attributed particular critical importance to this diptych if he focuses on and motivating it in the brief introduction to the book.

The fact is that the two photos, considered offensive, decontextualised in every sense, are conveyed by the web and the real world. Butturini is accused of racism. Such is the pressure of the controversy that Martin Parr is forced to resign from the Bristol Photo Festival’s artistic direction and to ask not only for the book to be withdrawn but destroyed.

One might think of it as a side effect of the Black Lives Matter’s campaign which, in its most acute phase, had, among its implications, the blatant demolition of many statues. Even if, as Tiziano Butturini, Gian’s son, points out, “this photo was not an error but the harshest example of social criticism”.

Evidently the book was a victim. Telling its story is important. So, it is Gian Butturini Association’s effort to save it from being destroyed, even though distribution is now impossible. All the more so because the decision to destroy it brings back the worst memories of the Twentieth century. The exhibition organised by Gigliola Foschi at the Scoglio di Quarto gallery in Milan was appreciable.

However, it is important to go beyond these considerations in order to get ahead; beyond the most blameless reasoning, beyond the most correct distinctions, beyond the aspiration to universalism that characterises the most open-minded thinking: all lives matter.

In order to understand the Black Lives Matter movement, it is necessary to reconsider history, the colonial basis on which not only welfare, but the Westerners’ gaze, has been built.

And to think that the United States, where until the Civil War black people were not even considered citizens and where Black Lives Matter was born, is still divided on this reconsideration of history. It is on the basis of colour that all this took place and it is on the line of colour that the claim moves.

More specifically, it should be considered that, since remote times, black people have been associated with the image of the monkey. As far as Italy is concerned, for example, Roberto Calderoli’s fact calling Minister Cecile Kyenge an orangutan at the Lega Nord party in Treviglio dates back to a few years ago.

All this does not detract from the impression of a revenge based on simplification, if not on regrettable manipulation. We must demand that a figure as Butturini be rehabilitated, respected in his intentions and understood in his results. As in other similar situations, it is necessary to clarify, to highlight, case by case. But it is good to be aware of the contradictions, the cultural tension, and the fact that sensitivity changes and the line between good and evil is constantly shifting. Butturini himself would probably have realised this. Meanwhile, the digital exhibition “Save the book. London by Gian Butturini” has been extended until 31 January.