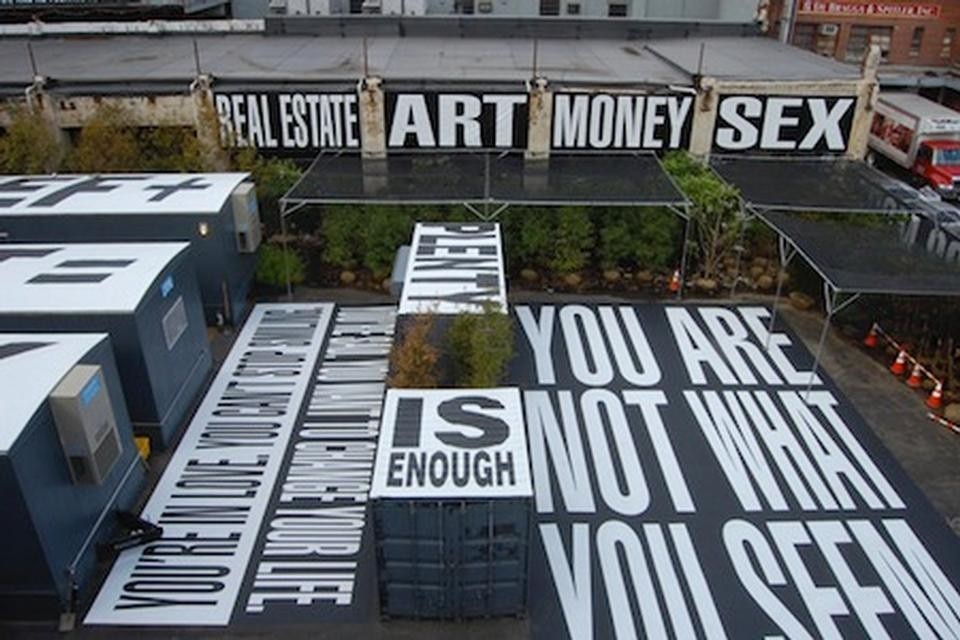

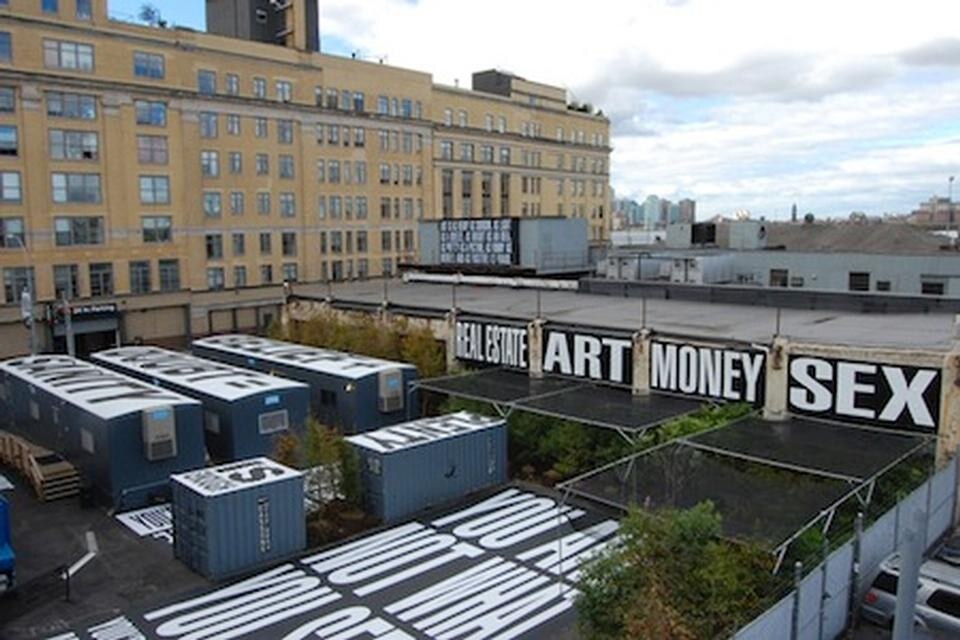

But if Kruger's self-assertion is true, if she is trying to picture being alive today, then there is something much more important happening in her work than a simple provocation of the contemporary art world. So when she plasters the site of the future downtown Whitney Museum in New York's former meatpacking district with phrases like "Real estate art money sex" or "Plenty…is enough," we need to understand something more here than a simple critique of art and excess.

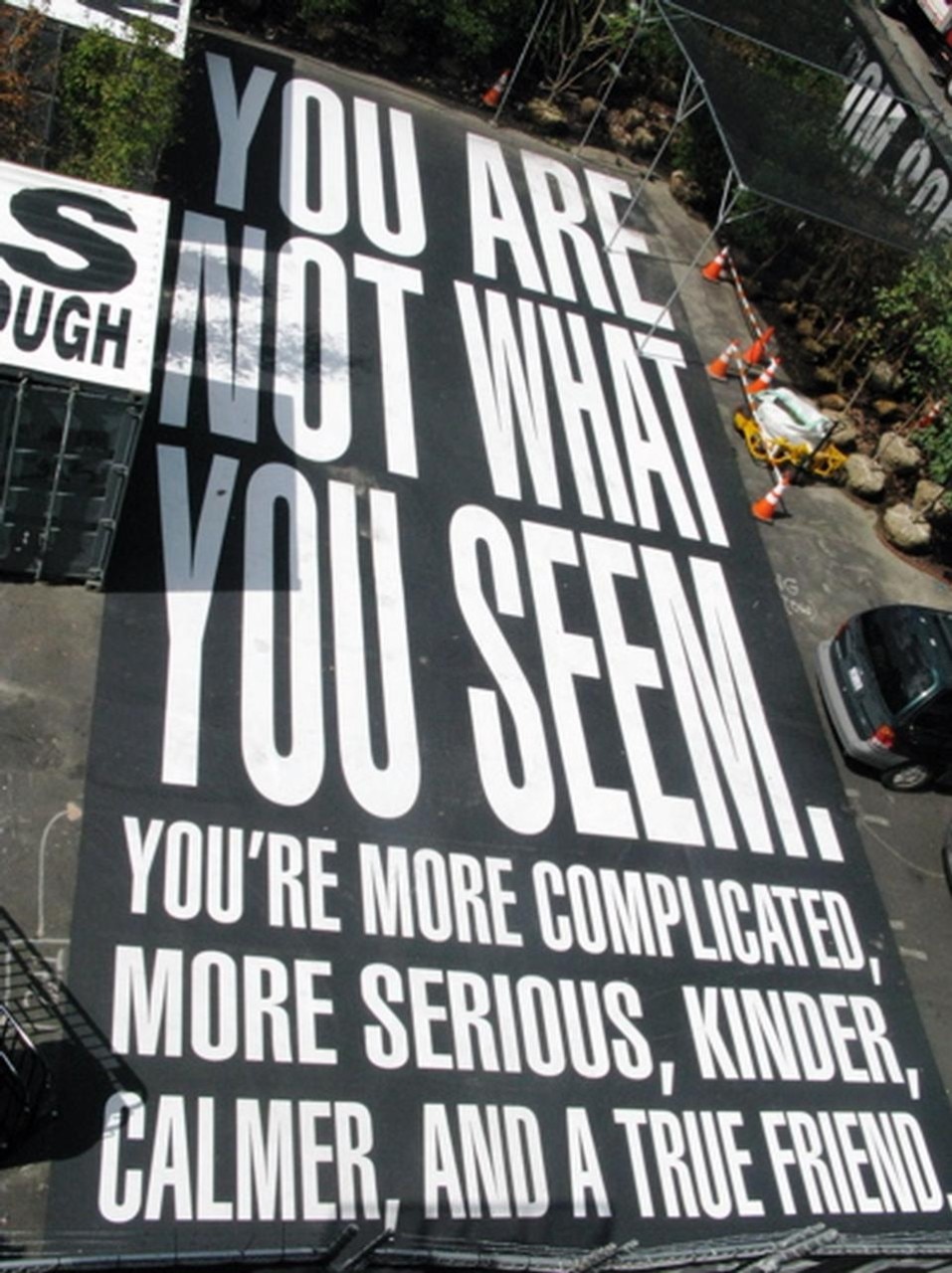

Indeed, this is why such phrases are supplemented by less expected invocations: "You are not what you seem. you're more complicated, more serious, kinder, calmer and a true friend," and "From blood to meat, to leather, to flesh, to silk." In the first sentence, the viewer is twice surprised. First, to know that they are not what they seem, but second, and more important, they are not told the obvious, say, for example: you are not an autonomous free individual but a part of a capitalist matrix of desire and greed. Rather, they are reminded, or perhaps even introduced, to their own qualities. They are not called on to criticize themselves, but rather to see how their being alive today amounts to more than being a consumer.

With the second phrase, Kruger takes us into a scene directly from the site's history as a meatpacking district. From the blood to meat is, of course, the movement from killing to consuming in the meat industry, but it is also the reverse order of consumption, wherein the blood oozes from the uncooked meat. But the image is also visceral and human – leading one to think perhaps of movements of physical and emotional passion. The addition of leather again moves the sign in multiple directions: towards the leather produced from the animals and the fashion district that the area has become, and also towards the sado-masochistic practices that occasionally sparked, and still ripple through, the nearby Chelsea piers.

We move then outwards in concentric circles to the flesh, the protective casing, and also the element that unites body and world, and bodies with each other in the grace of the caress. And then somehow we are given the final incongruous element: silk – a painstaking product of a worm, seemingly completely removed from the world of blood and meat and flesh (and money, sex and real estate) we have passed through. It is here that Kruger shines, and shines her light on being alive today in a world of this seemingly impossible balance of softness and pleasure, and abjection and violence. And each of these instances, as she reminds us, is but a "sometimes," but a "might" – we move through moments as we do through words on the page; we engage them but never fully; we are present but always pulled "from" and "to" – in a prepositional logic that unites the present to the past, the future, and the unknown.