On the edges of the silent Veio Park, along the Via Francigena and just a few kilometers from Rome, a tuff presence rests on the ground like a fossil unearthed from time. This is Casa Corrias, today renamed “L’Ammonite” (The Ammonite), a residence designed by Paolo Portoghesi starting in 1972, carried forward over thirty years, and now the subject of a new rebirth.

The new chapter of L’Ammonite opens thanks to the intervention of two musicians, Daria Leuzinger and Maurizio Persia, who decided to acquire the villa after stumbling upon it almost by chance while walking along the Via Francigena. From the very moment they entered, the new owners have been open about their desire to transform the villa into a place not only of life but also of cultural hospitality, a cradle of music and experiences. Fifty years after its conception, Portoghesi’s Ammonite is renewed as a living creature: rooted in the earth, open to the world, capable of hosting new narratives without losing the deep sense of the place from which it was born.

The project took shape during a transitional moment in Portoghesi’s career: already an established architect, a researcher in organic forms and the Roman Baroque, here he developed a residential idea that was both a return to origins and a declaration of poetics. Portoghesi – one of the most influential theorists of the twentieth century – is renowned for his central role in reviving tradition and elaborating Postmodernism in Italy, and his early reflections on the house resurface in the dialogue between historical memory and innovation that he promoted as director of the Venice Architecture Biennale between 1979 and 1992. His relationship with history was never nostalgia but a living source of inspiration, complemented by the “freedom of language” that he opposed to the dogmatism of Rationalism.

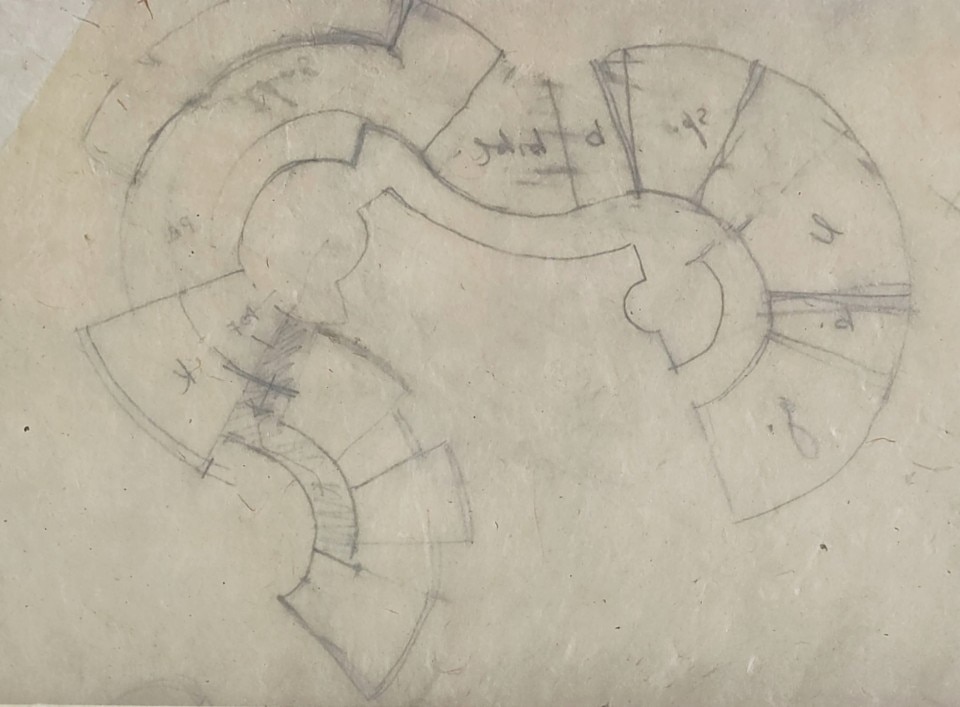

The house was conceived together with Giovanna Massobrio, at the time his assistant and later his life partner. It was she who introduced Portoghesi to the project commissioned by Ambassador Francesco Corrias and his wife, the American painter Frances de Villers Brokaw. The house’s drawings thus became the pretext for a sentimental bond: “For us, the Ammonite is the House of Love, drawing it four hands together, Paolo and I fell in love,” Giovanna confided to the new owners.

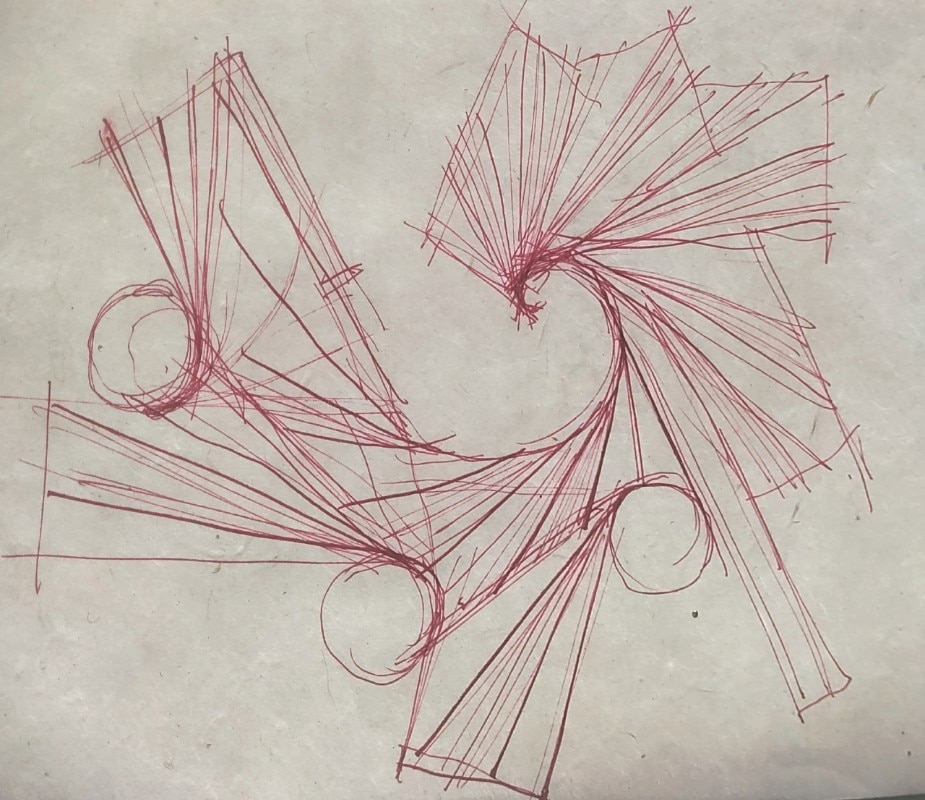

The gestation of the house, however, was long and not without problems, second thoughts, and changes along the way. Construction unfolded in phases, suffering interruptions and modifications, expanding the original idea. Portoghesi himself revisited the work years later, acknowledging changes that, by his own admission, strengthened its design power.

Fifty years after its conception, Portoghesi’s Ammonite is renewed as a living creature: rooted in the earth, open to the world, capable of hosting new narratives without losing the deep sense of the place from which it was born.

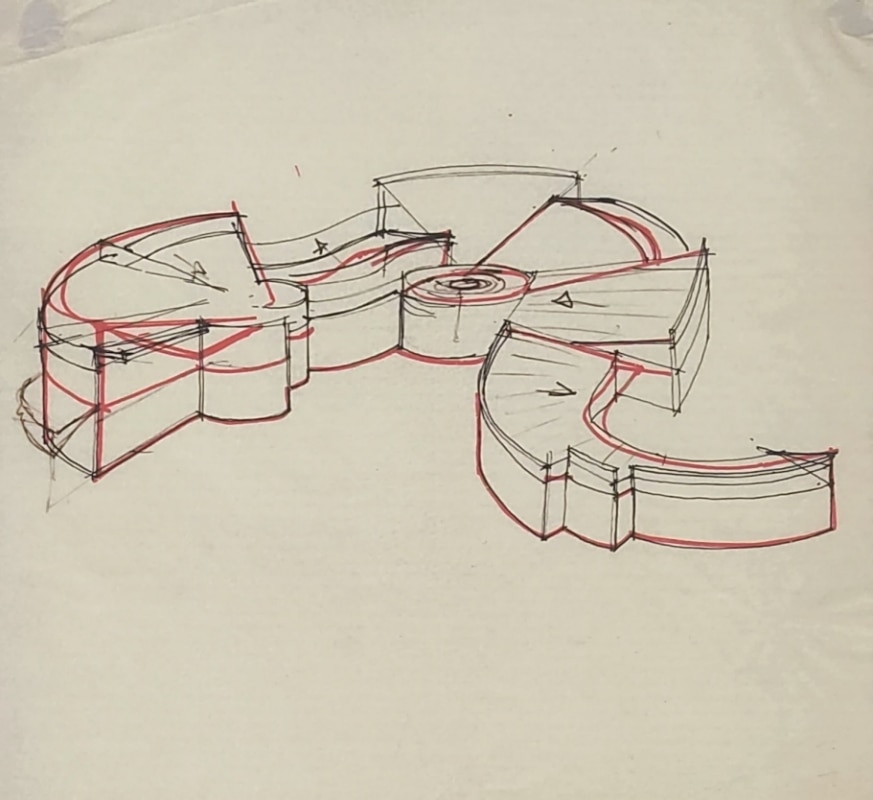

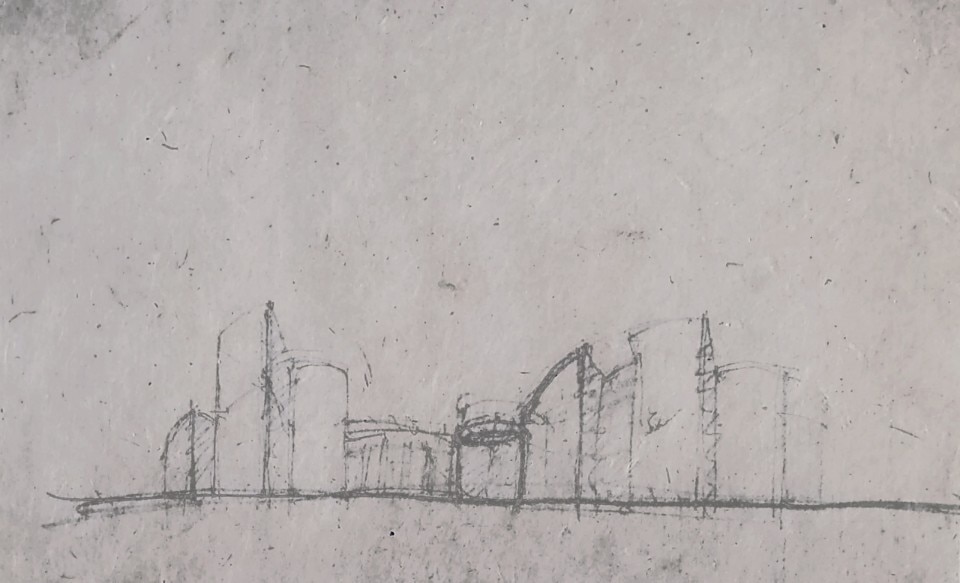

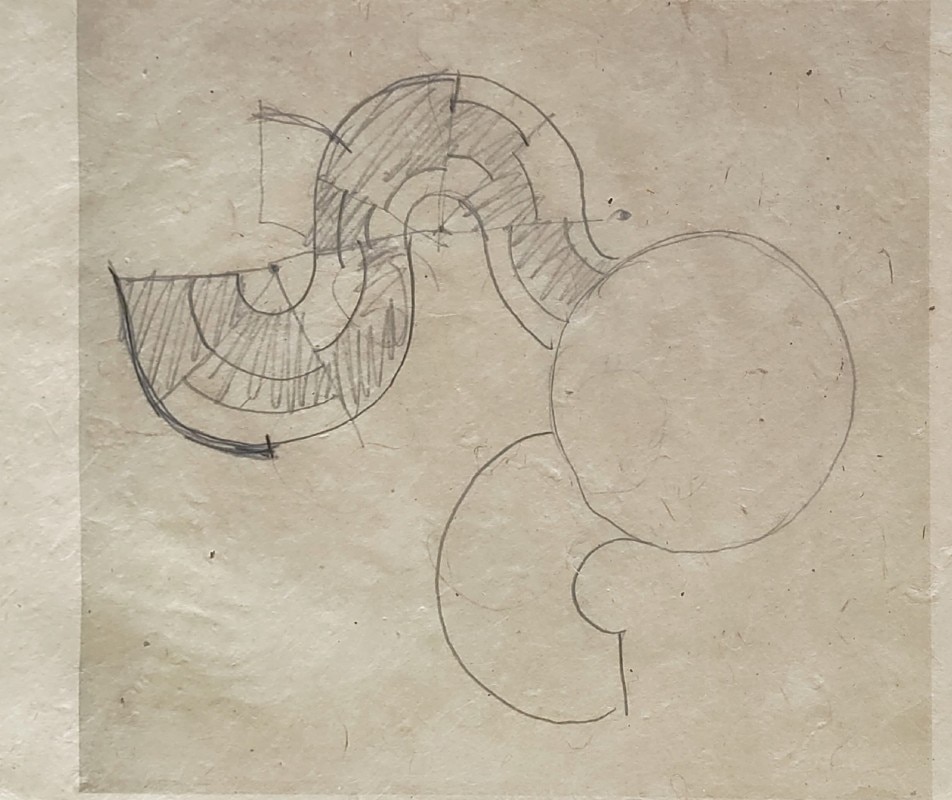

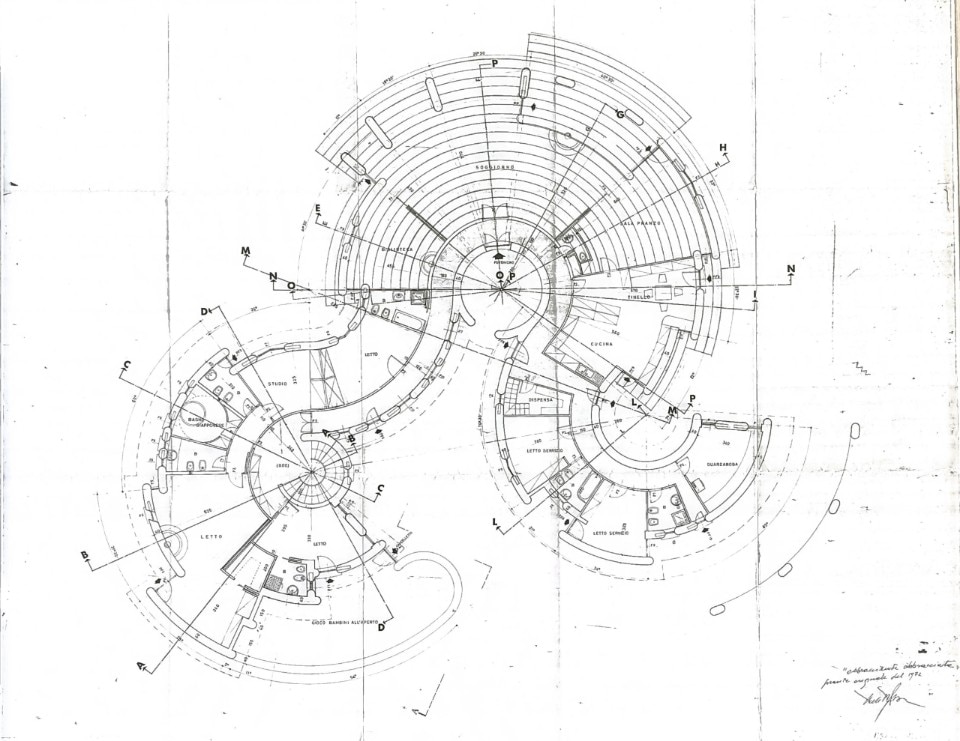

The form the house gradually assumed – evolutionary, fragmented, continuous – is the reflection of an architectural research centered on the concept of a polycentric micro-village. There is no main façade, no axis of symmetry: everything develops as a fluid succession of curves, towers, patios, and courtyards, each oriented specifically toward the landscape. The house, having no main elevation, appears different from every angle, like a creature that changes shape as one moves around it. On the concave inner side, it offers sheltered, shaded spaces, almost an architectural embrace that protects private life; on the convex outer side it opens instead to the panorama, dialoguing at a distance with the Sanctuary of Sorbo.

This interplay of concave and convex gives the house both intimate retreats, like a snake’s den inserted in the hillside, and visual devices oriented toward the history of the place.

Constructed entirely of local tuff blocks and covered with truncated-conical roofs tiled with terracotta, it evokes rural Lazio architecture reinterpreted through Borromini thought and organic design. The main entrance is in fact one of the three pivots of this village-house.

As in a reworking of a Roman impluvium, the area in front of the entrance is a completely open circular space, where one pauses temporarily, as if awaiting access to another dimension once past the threshold. Beyond the perpendicular corridor, one arrives in the main hall, which reveals its opening to the countryside through a glass wall that completely replaces the south-facing façade.

It should be noted that, as Portoghesi’s first drawings show, this area was originally intended as an immense paved patio, entirely open to nature. The fan-shaped hall separates the second core of the villa – dedicated to services – from the third, where six rooms of different sizes form the family area.

From both outside and inside, one perceives how the curves and counter-curves are almost tangent rather than overlapping, precisely to create slits that become openings for light to penetrate the villa, as well as striking vertical devices framing views of the land.

This attention to framing the surrounding landscape culminates in the third core of the house: a truncated medieval-style tower with Borromini hints in its spiral form. The tower leads to a second floor of rooms in the master area, giving access to a terrace overlooking the roofs and valley, reaffirming the layout of a medieval village from Italy’s communal era. From here, some carvings open onto Monte Razzano, with Campagnano behind it, the Sanctuary of Sorbo, and the surrounding countryside.