As founder of Baustelle in 1996, singer, writer, songwriter, composer and — needless to say — a major Gucci icon, it is quite a surprise to learn that Francesco Bianconi had never landed on the pages of Domus so far. Of course, we are used to locate his figure within the music realm. Still, the lyrics he has composed through the years have always had the capacity to literally build the worlds they evocate around the listener. The navigli in Un romantico a Milano (A Romantic in Milan) before they became Navigli™, countless different apartments, the Esselunga department store a friend had tried to rob in La guerra è finita (War is over), the streets where pale miniskirts used to stride, while yé-yé was coming (Arriva lo yé-yé).

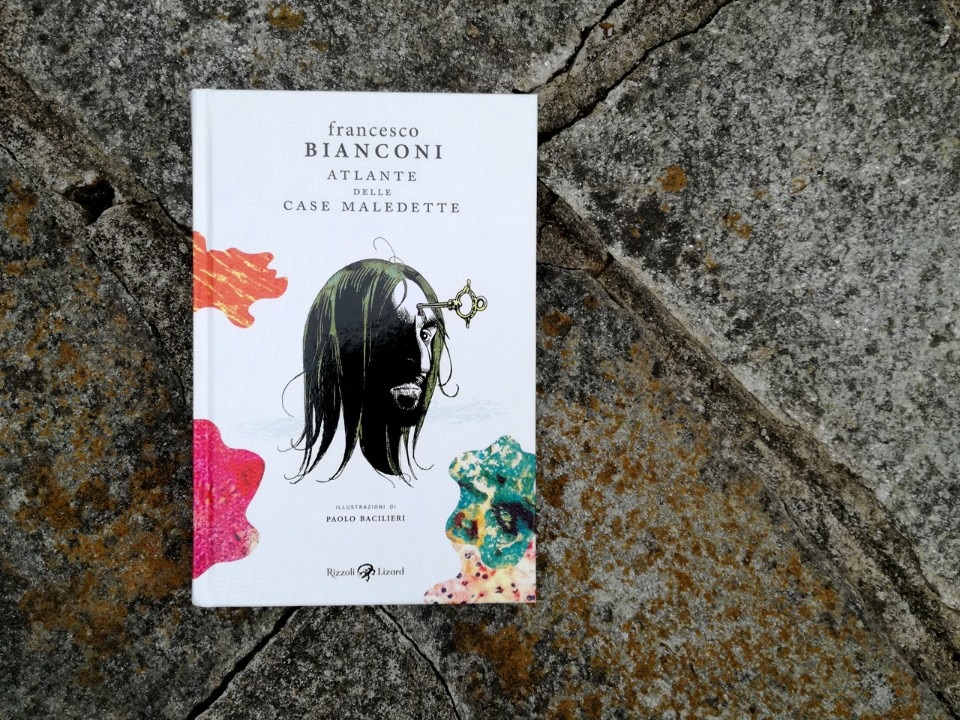

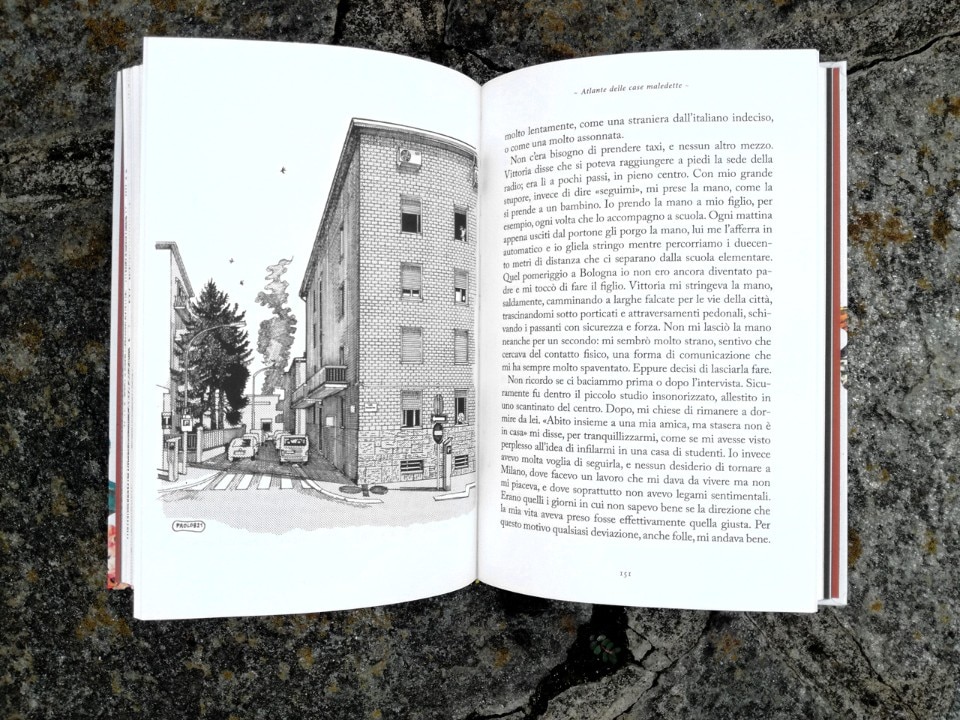

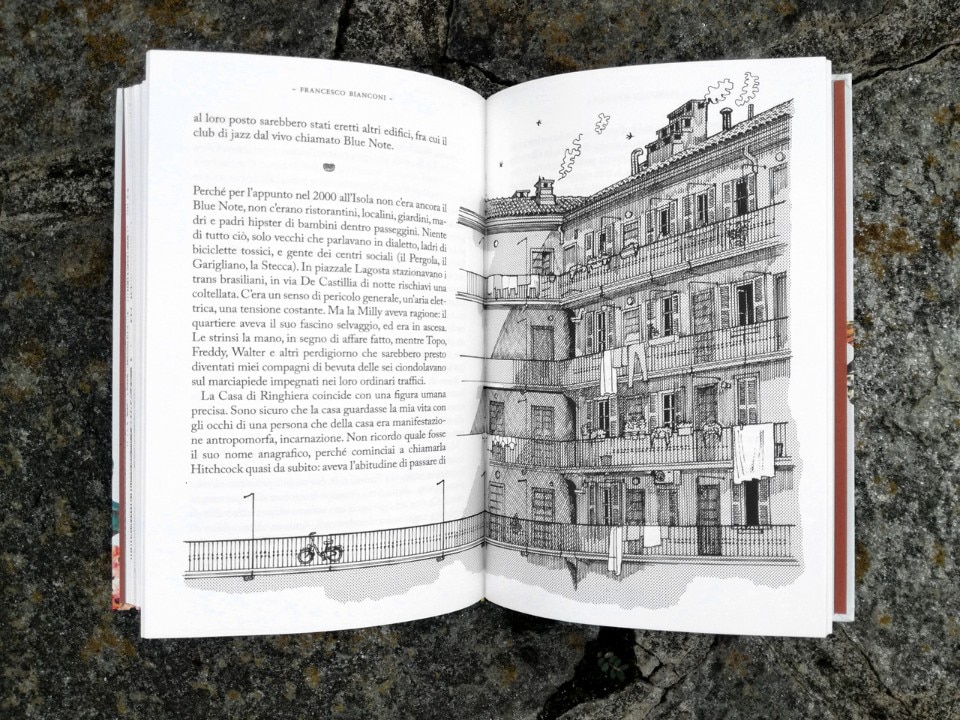

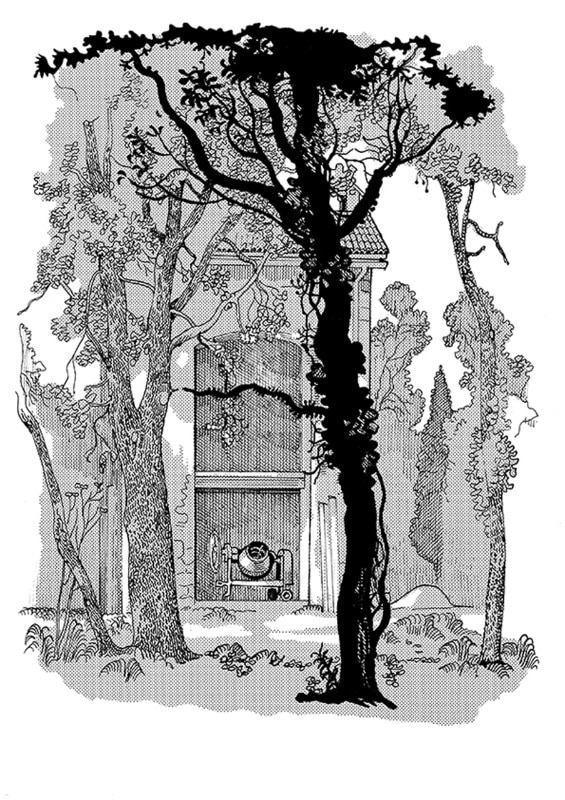

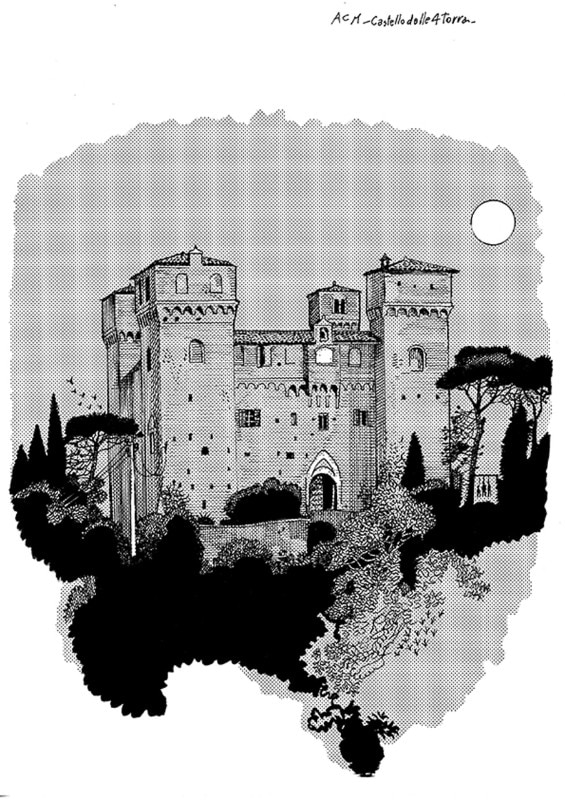

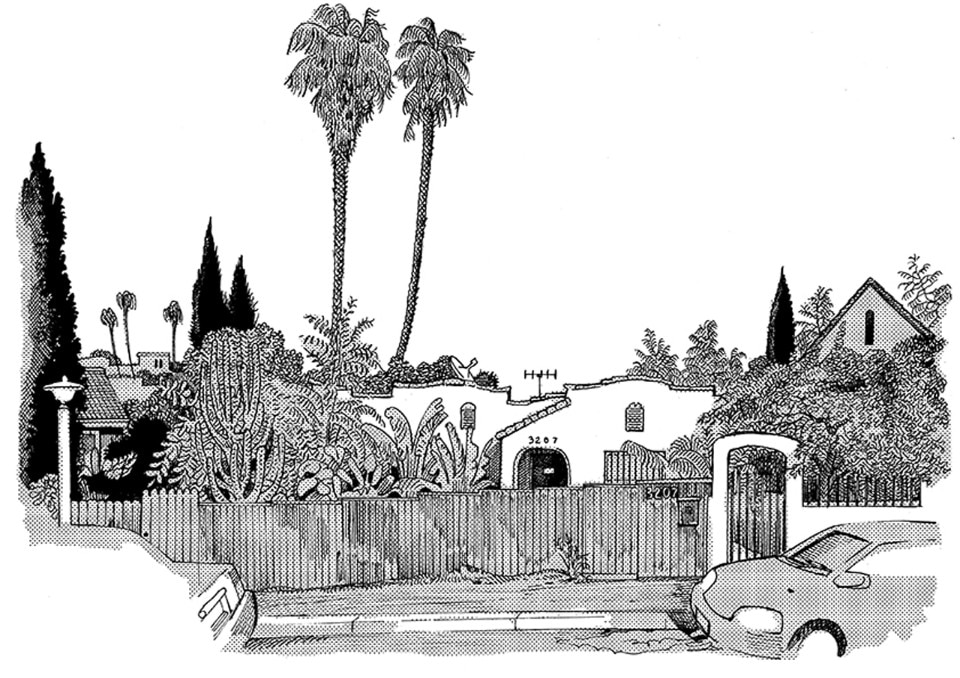

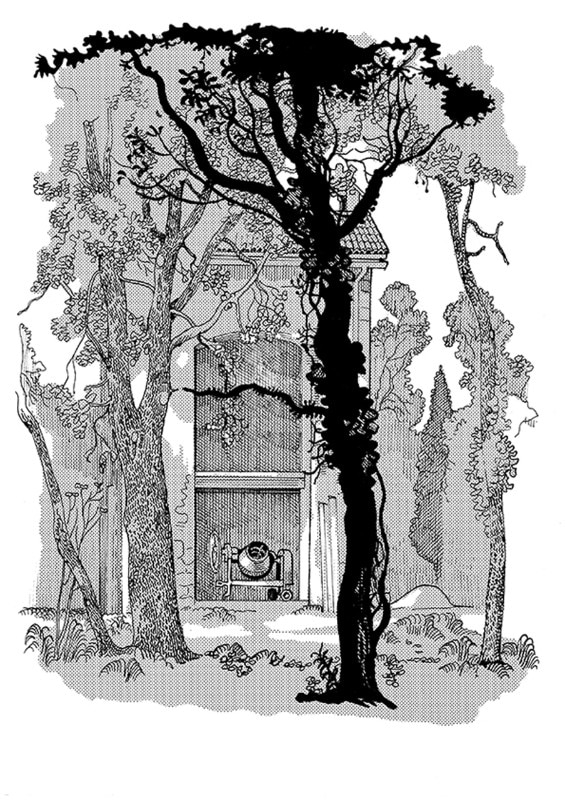

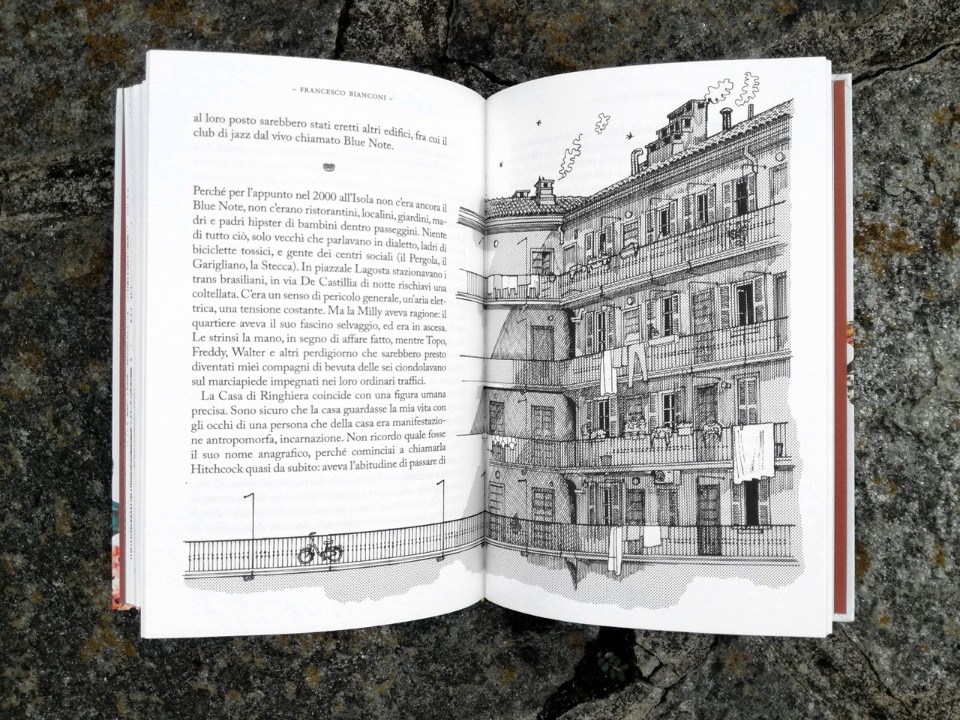

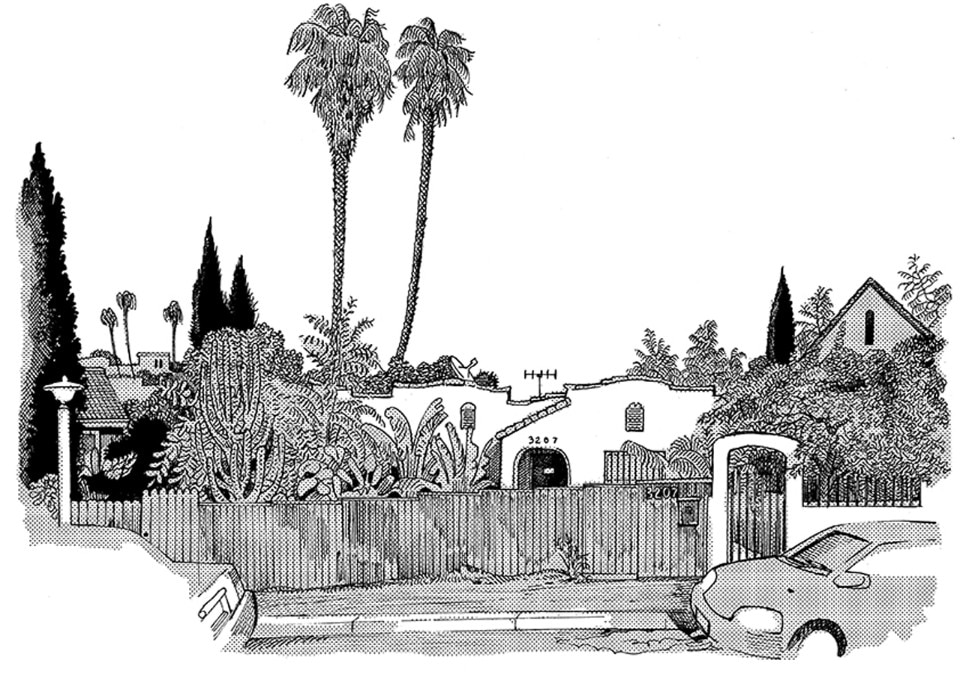

Finally, while Domus was undertaking the creation of its collective quarantine diary, Bianconi has written a book made of houses, where more or less domestic interiors gather to give both shape and expression to a biographic story. The title is Atlante delle Case maledette (Atlas of the cursed houses), the book was published this spring by Rizzoli Lizard, and illustrated by artist Paolo Bacilieri. Domus has exchanged some words with Bianconi, halfway between order, death, life, salvation and the Chelsea Hotel.

As in any good building: foundations first. How was this book born?

Quite by chance, let me say. The core idea for this book came to my mind shortly before the pandemic, I was out buying groceries and I asked myself: “How many houses have I entered in my life?” This quickly escalated up to: “How many houses an average Western human can enter in their life?”

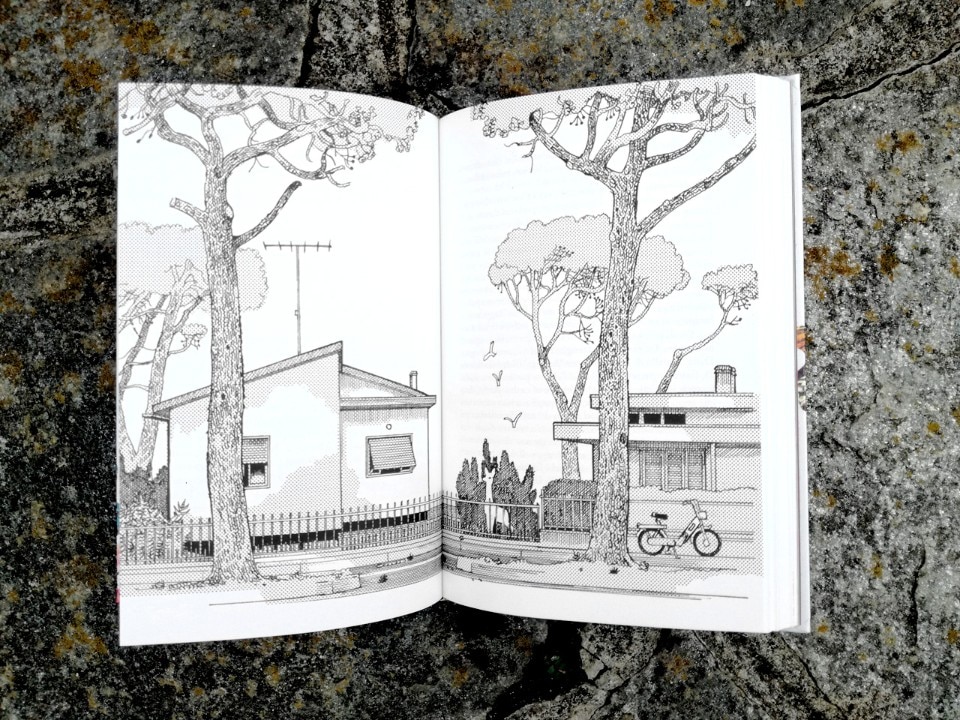

I started thinking of my experience, many images came flashing to my mind, architectures and interiors, many indeed, houses where I had spent time, maybe even one night only. Not places where I used to live, but houses I had lived, somehow.

So I thought about writing the story of a man who decides to make such kind of list, thus tracing the story of his own life, while he is locked down inside his house because of a global widespread threat, which at the beginning I had chosen to leave unnamed. Then coronavirus broke out as I had just started writing, I found myself taken over by reality and its tragic effects. I had to choose, so I made a choice and gave the threat a name: a virus, although still unspecified.

Why had this work to necessarily be a book?

I had been thinking about writing a book for a long time, and this idea of a “reverse novel” sounded convincing to me: deconstructing a narrative typology by moving from the particular (the houses) towards the universal. A choral novel, the story of a human being, sung by a choir of houses.

Where did the idea to work with Paolo Bacilieri come from?

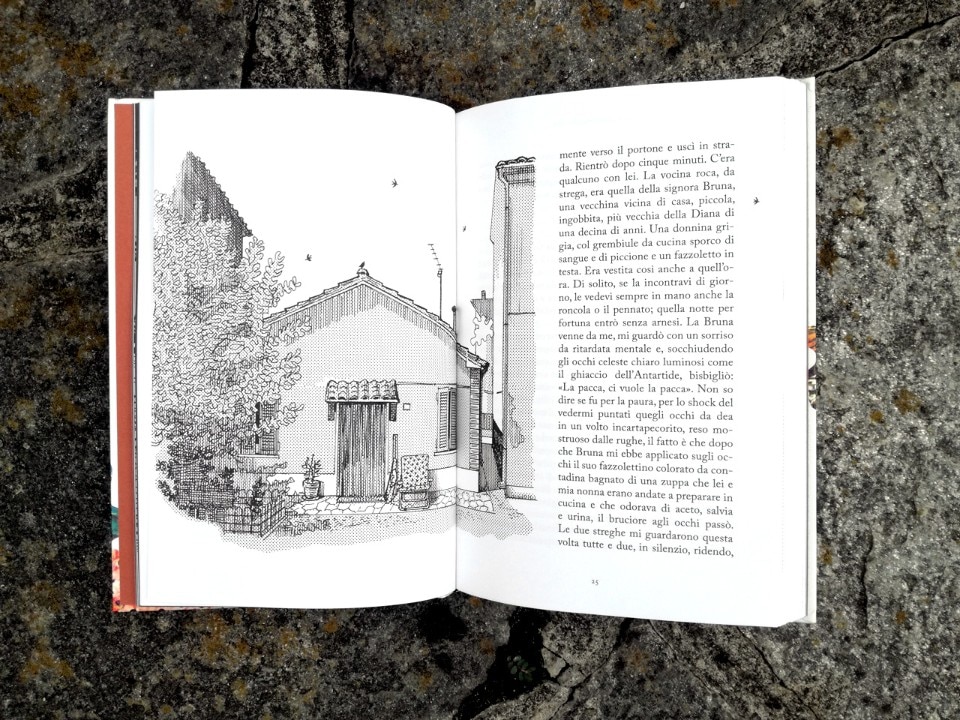

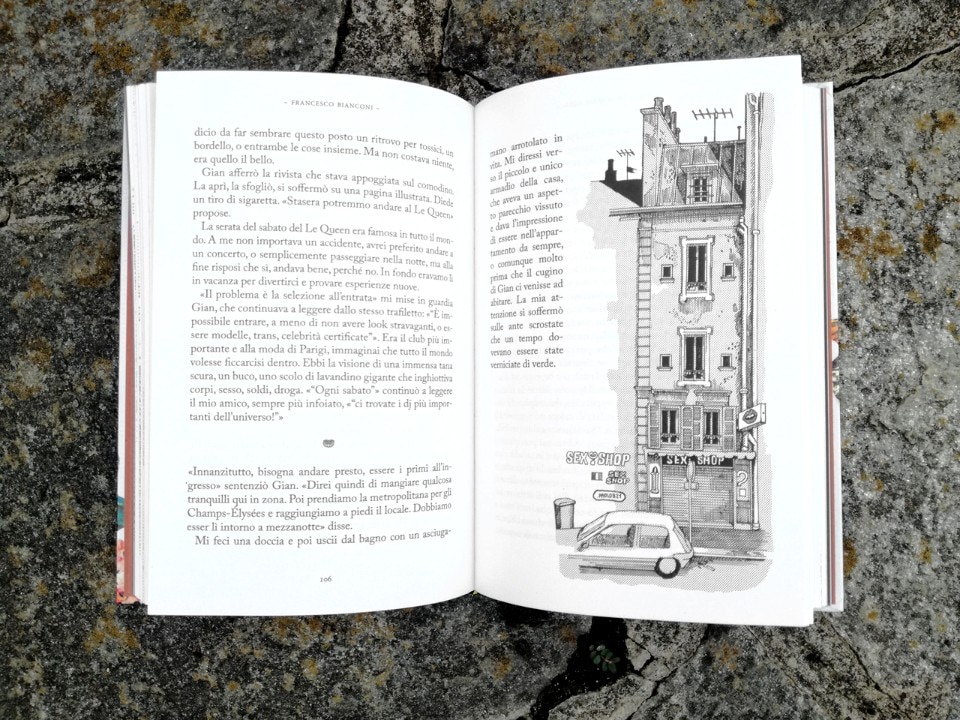

I didn’t know him personally. A friend working at Rizzoli Lizard encouraged me to create an illustrated book, they proposed Bacilieri and it was a great success. I had always liked his style: I’m passionate in everything aiming to realism in illustrations and comics, I feel a stronger attraction to details. I see myself as a fan of Guido Crepax and Milo Manara.

All across the book, one can hardly find a point where an explicit statement is made about houses. Except in Bologna, when Vittoria says ‘I hate houses’. Well, is this you?

No, this is not my position about houses. It’s a fictional character’s point of view, channeling that radical, trenchant attitude you can find in students, like in Bologna as an antonomasia of such kind of spirit.

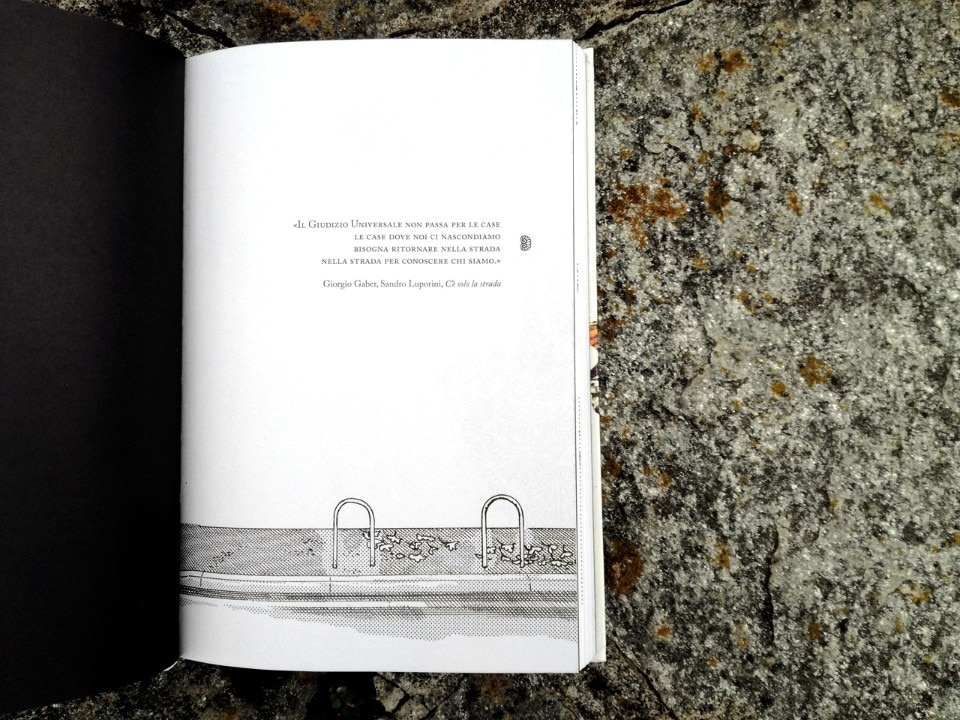

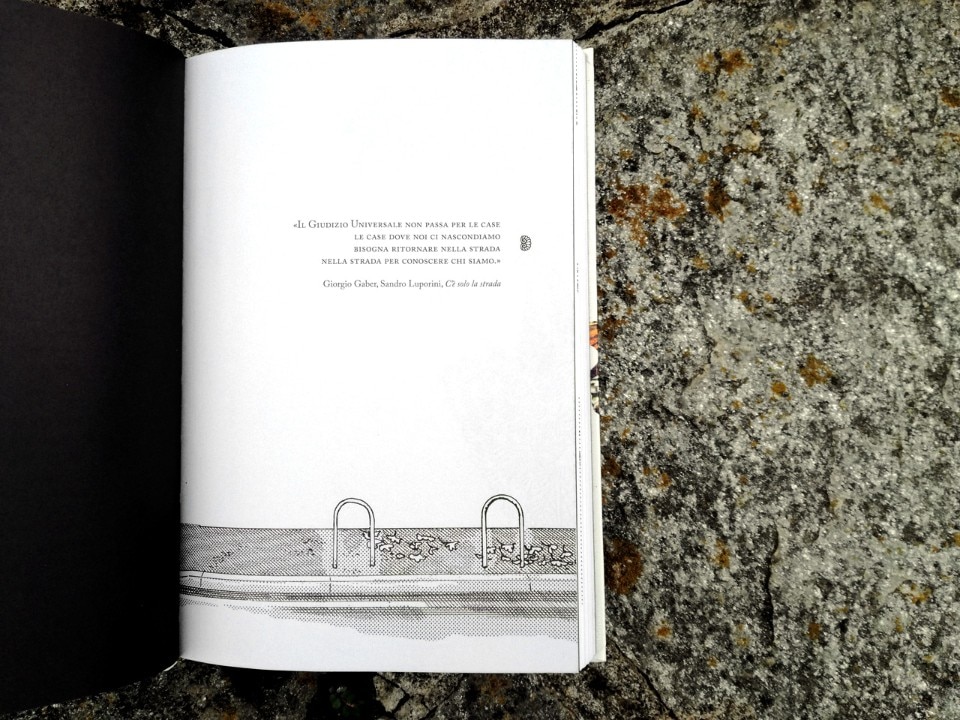

I don’t agree with that. I love houses, I’m fascinated by houses. At the same I perceive their deathly potential. Houses have made a long way from their original function of shelters, as the main character of my Atlante says, in this part of the world houses have acquired new values and meanings, including all possible degenerations or distortions. Life as a whole happens there, in houses that can consequently become the stage to real tragedies. The book’s exergue did not land on that page by chance; those lines were composed by Italian songwriter Giorgio Gaber with Sandro Luporini, [and they sound like]: ‘The Last Judgement won’t pass by the houses, those houses where we hide. We have to come back to the streets, to the streets to understand who we are.’ We can get to know ourselves inside our houses, still at the same time we have to be brave and keep those houses open, to open up our minds to knowledge. Western houses can turn so often and so easily into comfort zones, with humans becoming the prisoners of those hotels they have built for themselves. Exploration and knowledge are discouraged.

Such interpretation of the notion of ‘feeling well’ at home, and the opening lines to your book create a contrasting environment that made me think of the house where I grew up. I dream of that house almost every night (and I must confess it’s quite exhausting), I have discovered its stories long after I left. Does your Atlante also include similar places of origin?

Sure it does, la casa nella casa (The house within the house, the second chapter). When I was a child, I used to live in a small town, in a big house that my parents had just built. Lots of room. A room in particular, wonderfully empty and still unused, just the white walls and the wooden floor: I stored Dash washing powder boxes there, filled up with toys, and it became the perfect playhouse for me and my two friends, who used to come over almost every day. I was scared to get out of there — as Dimitri, my fictional persona, also is — all along that childhood of mine that was nonetheless happy. I was scared to go out for a walk, passing in front of the bar where the adults and the elderly used to hang out, and facing the risk of someone saying hello and asking ‘Ciao bellino, dichissei?’ (Hey kid, who do you belong to? who are your parents?), as they say where I come from.

A lot of what followed in my psychologic life — this book is largely autobiographic — may have had its origins in such voluntary lockdown, imposed by no one else but me: I had built my own comfortable home, my safety.

Many aspects of human lives — mine for sure — can be explained through certain houses, through the relationship that each young human being had established with domestic environments, with interiors, when they were children.

Feeling at home might take on some more problematic meaning, at this point.

Of course. No one is safe. Ever. Safety is a big lie.

The problem itself of safety is ill-posed: houses are usually identified as a safe place, maybe because of their primordial function of shelters, as we said, contrasting the mystery of the unknown, — of a chaotic, uncontrolled outside where literally anything might happen to us — with the power of defined, known spaces. That is where the mistake lies: the known, as Canetti says, is the order, inevitably tending to death. The known dies, the unknown only can be vital.

I think we are evocating issues of control. The domestic environment has been largely studied in this sense — I think of the work by Beatriz Colomina, of the interpretation of last centuries’ Western homes as control devices used against women, bodies, against pleasure itself. Turns out we the architects might result being real criminals (and I won’t be the one to deny it).

I agree that every project always carries in itself a component of control. It would be a great challenge to try and realize the uncontrolled: something like a dada performance.

Still, I am also very interested on that kind of control that inhabitants use on houses. Human beings usually make an anchor of their house, just to resist their tendency to go adrift.

I’ve seen houses that belonged to people known as visionaries, ‘artists, writers, whatever kind of supposedly chaotic personalities, and these houses would sport the tidiest libraries and collections of objects, of fetishes. Let us think to the Vittoriale degli Italiani, the artwork-villa on lake Garda assembled by poet Gabriele D’Annunzio: objects, everywhere, but such hoarding was subject to the strictest organization.

What space was the funniest for you to write about? Or — maybe this is the right question: did you have any fun in writing this book?

It’s an interesting question. Usually — not always though — I have a powerful drive at first, but the real pleasure comes at the end, as it is the end of some kind of suffering. As I dive deep into writing, into a prose engaging me for a long time in the making, unlike songs, I find myself alone with parts of me which I’d probably prefer to leave locked down in some personal inner cellar.

Feels like home, then.

Exactly. But where is the pleasure pushing writers to write? At the end of the day, in my opinion it feels like having fought some kind of a small battle, where you finally won, where you won once you have made it, once you have finished your text and fed it to the world.

This is quite a common tendency in contemporary literature, after the crisis of classic novels: the so-called autofiction, writers pouring their real self into the pages, like (Emmanuel) Carrère. He might be a big narcissist, but I can see his pain in writing what he wrote, and to me this speaks like the greatest added value. He might also be lying, but I would still perceive some fundamental sincerity.

The question becomes: which spaces have costed you the most in this writing process?

The first chapter, la casetta (the small house), my grandmother’s house where I spent much of my childhood, has been painful to write. The same happened with the seconda casa al mare (the second house by the sea) because, just like it happens to Dimitri, the holiday house becomes the places where everyone starts screaming from back in time, and the owner discovers he’s got old as he faces the pile of memories that have been unconsciously stacked in that place.

These are the most designed sections, they look like the result of a design process, of an attempt to give materiality to something that had just come up impromptu.

Now, the time has come for a plot twist: how has Bianconi’s house got to be like?

Good timing: I just bought a new house.

I don’t like houses that are too big, I just moved from 80 to 130 square meters, and it looks enormous to me.

I love to live in the city. Alright, I am fascinated by the hermit’s dimension as well, but we might consider this for another moment in time.

What else? I prefer old houses instead of modern, but to me this makes sense only in Milan, where I live.

Kitchens, then. Kitchens are my favorite spaces. I also like bedrooms, but the kitchen and the living room are more important to me: there is where I live, I think it would be ok to even sleep in certain living rooms.

No home-and-workshop fascination?

That is different. The house I am leaving, for instance, has another apartment downstairs, working as my ‘workshop’, my studio. This will remain, while my home will be moving instead; and this is good for real. I experimented a situation of home-to-studio minimum distance, and it worked well, but now it would become working from home, and that would be pure hell to me. Now, some home vs. studio separation helps a lot.

Your last album, Forever, was recorded in Bath, wasn’t it?

The core has been recorded in Bath, the piano and the string quartet. All overdubbing has been made between New York, Los Angeles and here, home-workshop-studio.

Do you believe in the power of legendary creative places, the retreat, the iconic studios, the Chelsea Hotel and so on?

Not as much as to say — as some do — things like ‘you can really this thing was recorded in that retreat/at the Chelsea..’

It ain’t necessarily so. I know of some recording projects that included renting mindblowing studios overlooking, like, the Faraglioni in Capri, which ended up in epic failures. La voce del padrone by Franco Battiato, then Patriots, and L’arca di Noè, all that golden age of Italian pop music was recorded in a small studio created by Alberto Radius, the guitar player, some kind of a home studio with no windows, that he had set up in his cellar, under an apartment block in piazzale Susa, Milan.

Well, in a way, when your home is also your studio, this can help you not to feel the pressure of studio rent time running out.

But you might feel the pressure coming from being at home.Yes, that is dangerous as well: you have to be a good manager of yourself. I don’t believe in any endless ‘let’s play it again’. I think that a moment comes when you got to wrap it up. There is a whole world of possibilities around you, and time comes when you have to make a choice, cut one precise little slice of all that infinite potential, and bring it home, made real at last.

This got me thinking of the troubled birth of Exile on Main St. in that infamous villa on the French Riviera. Such stories of places of creation becoming places of no return still keep generating fascinating mythologies.

Yes, by those times the Rolling Stones had the taxmen on their back, and when they were advised by their manager to choose between paying and going to jail, they all just fled to Côte d'Azur and bought a villa — no fools at all — except Mick who would stay in Paris living his socialite life and going back and forth.

For sure there is a lot of mythology around the epic sessions in Keith Richards’, but — if I’m not wrong — there is very little of the Riviera recordings in the final album release. There must have been a lot of re-recording somewhere else, maybe they just realized their Riviera production was shit (sic) and decided for a remake. Places can often be inspiring, not always.

Otherwise, you choose the Happy Mondays solution. You realized you did not write one single word for your songs, so you choose to deliver a fully instrumental album.

Exactly. In that case the story took place at the Hawaii islands, in fact.

Humans remain nonetheless the foundation of it all, they are the ones who build houses. All the good and possible bad lays within human beings at first: it’s the humans who keep creating the humans.

- Libro:

- Atlante delle Case Maledette

- Autore:

- Francesco Bianconi

- Illustrazioni:

- Paolo Bacilieri

- Anno:

- 2021

- Casa editrice:

- Rizzoli Lizard