The reconstruction that followed the Second World War, born out of necessity and as a result of the economic policies implemented by the newly-established Republic, saw a violent acceleration in the construction sector and a rapid development of the urban fabric of Italian cities – particularly that of the great industrial and political centres, including Milan. Though the Economic Miracle per se only lasted between 1954-1961, the shockwave spread at a steady pace throughout the following decade, shaping the cities we live in today and the macro-areas within which we move every day.

It would be wrong to interpret post-war Milan solely in terms of the ‘super-production’ fuelled by speculative appetites when, instead, it was a period of great cultural ferment, thanks to the desire to update building types, materials and construction techniques to accommodate the changes of a rapidly evolving society, ready to embrace new lifestyles and a new taste. The momentous nature of this historical period sparked a natural debate – the opposite sides of which can easily be identified in the magazines Domus and Casabella-Continuità – on the best course of action: whether to rely on the private initiative of the new bourgeoisie or on public initiative, whether to import styles from overseas or promote continuity with the Lombard tradition and the existing environment.

The ideological nature of the debate influenced Milan’s architectural culture for years, and some of the most active architects of the period paid the price. While one part of the press immediately welcomed their projects with the urgency of publicising their innovative character among architecture insiders, the other rejected them as harbingers of a merely ‘illusory’ quality compromised by the market, a judgement not without ambiguity.

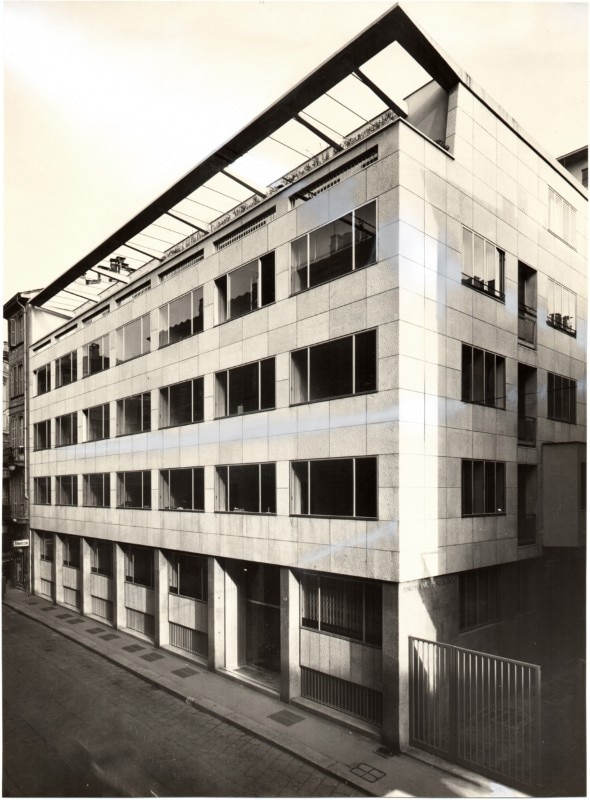

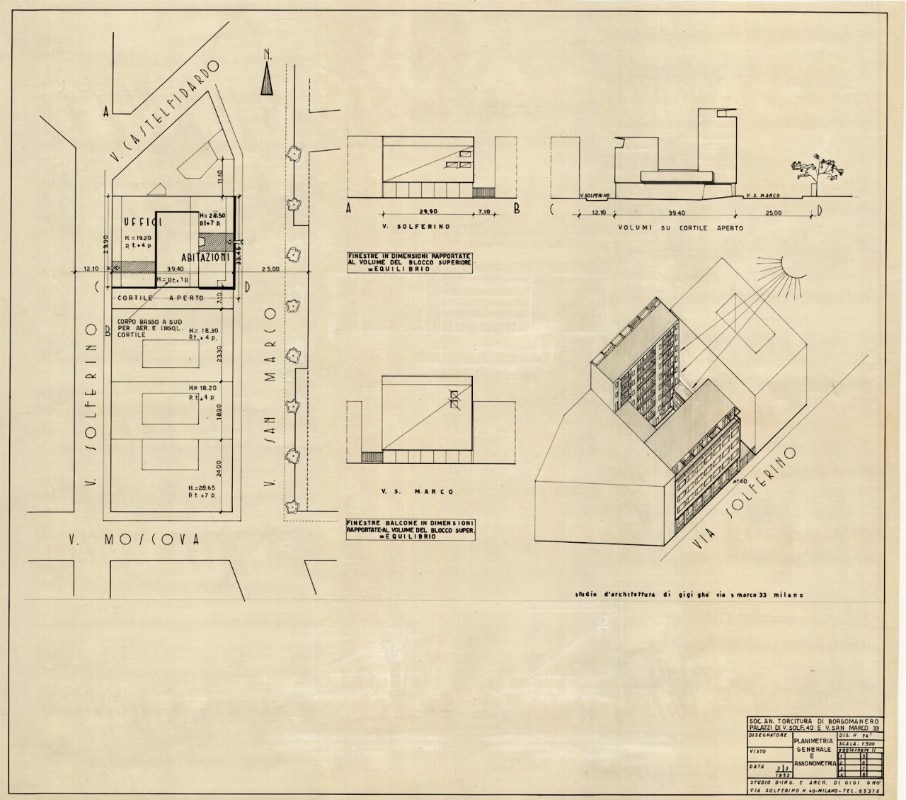

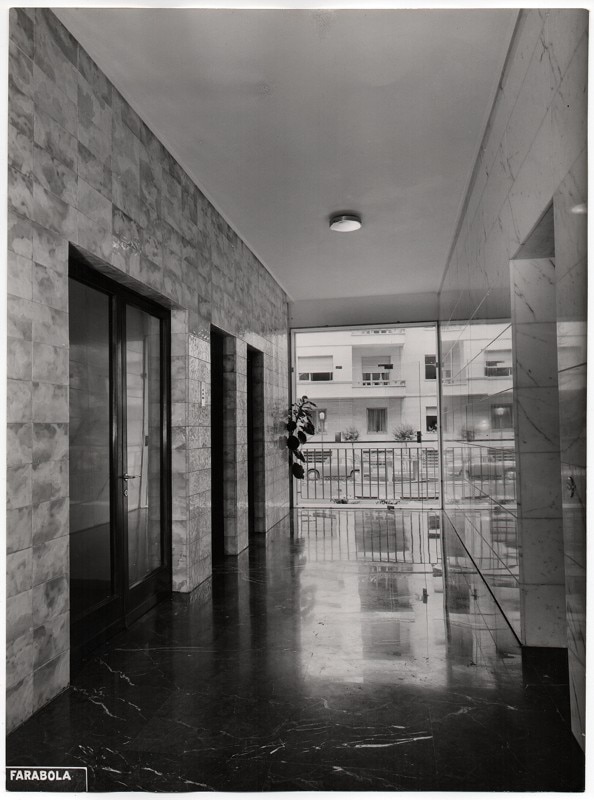

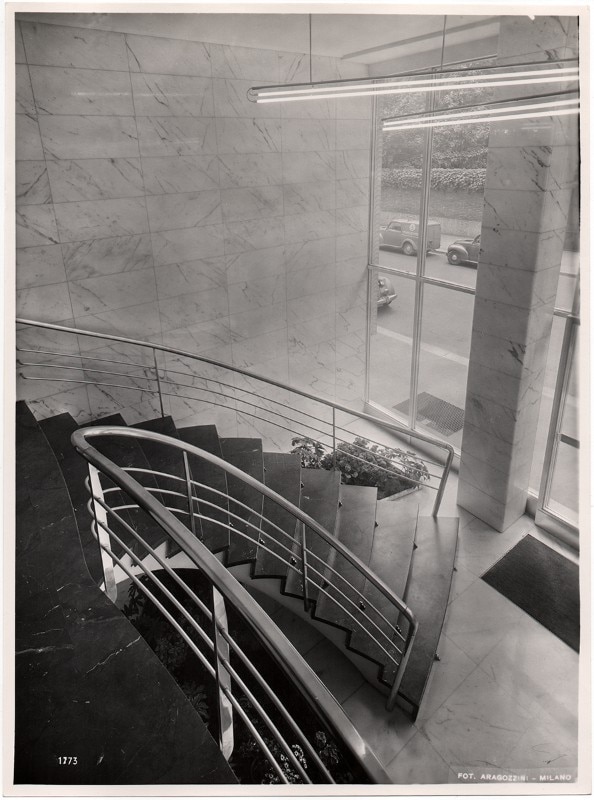

An emblematic case is that of Gigi Gho’, an engineer and architect who trained with Gio Ponti – the two were connected by a deep friendship and mutual esteem – and became independent in his early thirties. In Milan, he designed the headquarters of Torcitura Borgomanero and the Residential building in Via Sant’Antonio Maria Zaccaria with a light sculpture by Lucio Fontana and ceramics by Fausto Melotti in the hall.

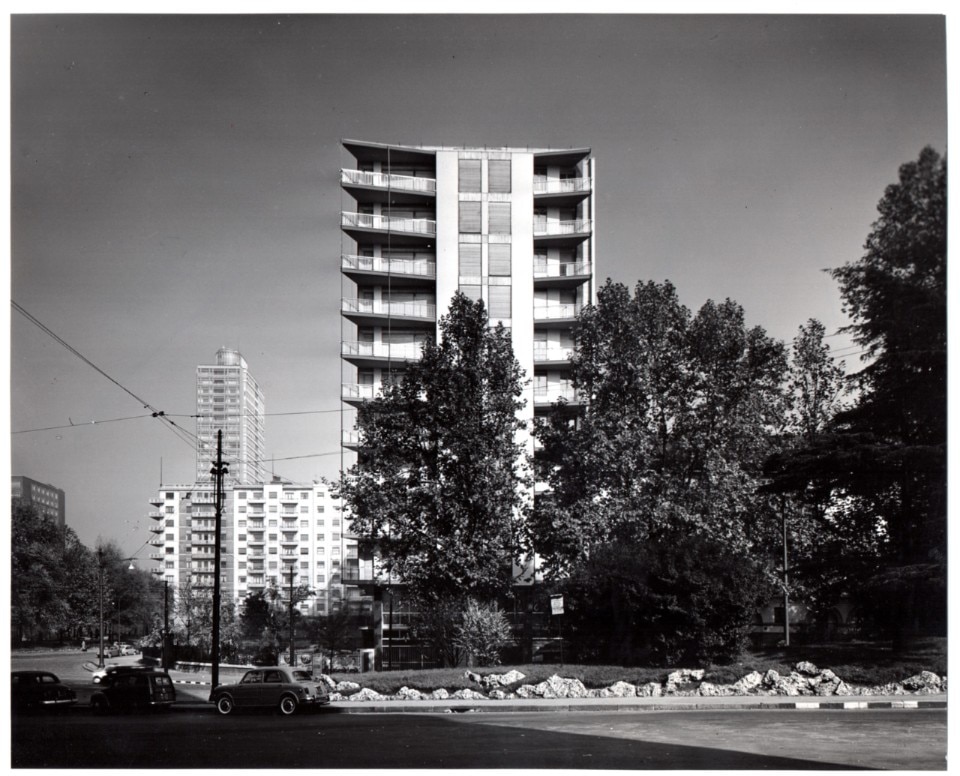

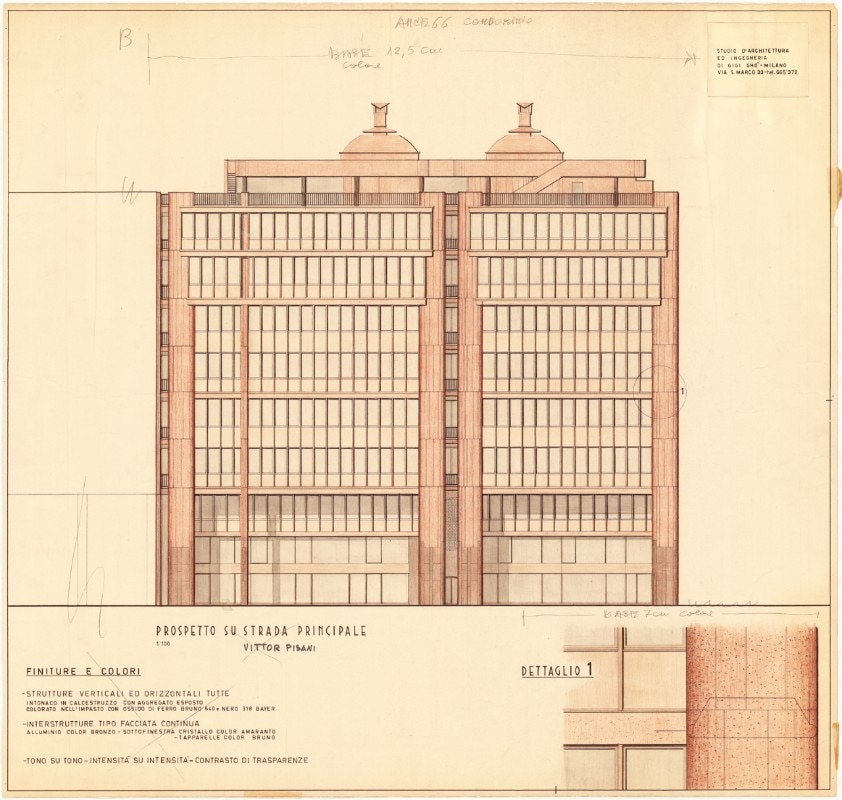

Also in Milan, Gho’ designed the iconic building in Piazza della Repubblica with corner-balconies allowing a 270 degree view of the city’s monuments, the headquarters of Co-Fa (now Bayer) in Viale Certosa and the buildings at 4-6-8 Via Legnano, in which the composition of the façades is inspired by the functional organisation inside, and the careful study of colour stands out both in the interiors and in the exterior cladding.

It’s a shame that the rediscovery of Gho’ and other architects of that period such as the Soncini brothers, Magnaghi, Terzaghi, Mattioni, Asnago, Vender and the Latis – to name but a few – has only taken place in recent times, leaving these figures for years on the margins of official historiography, “relegated to the interest of a few scholars and admirers”, as quoted in Il professionismo colto nel dopoguerra, edited by A. Sartori and S. Siuriano (Milan: Abitare, 2012).

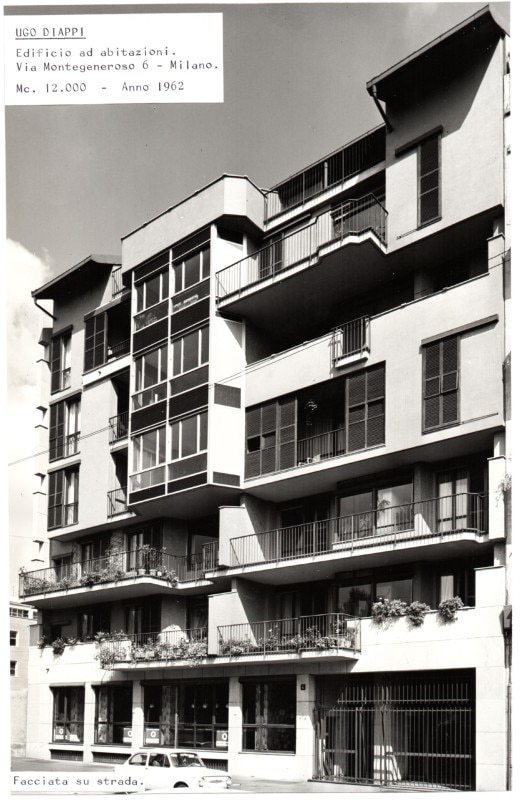

It was precisely the desire to promote his work and make it known that led Gigi Gho’’s son, Cesare, to set up in 2017 an archive of his father’s projects, entrusting its curatorship to architect Alessandro Sartori. Realising the need to provide the widest possible access to the material in his possession in order to ensure the widest possible dissemination, he arranged for the minimum essential documentation – consisting of drawings and photographs from the period – to be digitised and immediately made available online, allowing for an initial reading and understanding of Gho’’s projects. More detailed material, on the other hand, can be consulted only on site. This unusual choice has allowed the discovery of little-known projects, such as the residential building with overlapping villas in Via Monte Generoso, as well as the proliferation of initiatives – including the first monographic exhibition in 2021 – and collaborations with critics, photographers and scholars, including Marco Biraghi, Lorenzo Degli Esposti, Sosthen Hennekam, Daniele De Lonti, Matteo La Macchia, Robert Ribaudo and Luca Trevisan.

The Gigi Gho’ Archive is undoubtedly a virtuous example, which inaugurated its activity at a particularly significant time. The lack of information caused by years of only partial narration of the post-war period is worsened today by the fact it is no longer possible to draw on the direct testimony of the excluded protagonists and by the deterioration of their paper archives, which urgently need to be digitised and catalogued. What is more, given the obvious difficulties that private individuals face in preserving and disseminating material, as documentation is handed down to new generations, certain designers are further pushed to the margins of historiography, out of sight and off the radar of historians and curators. It is therefore necessary to intervene to protect, promote and systemise all sources, whether they belong to private institutions, public institutions or are still in the possession of heirs, creating a platform that allows for easier access and a homogeneous use.

Interest in Milan’s post-war modern architecture is not only of a historical nature: today’s architects can find in the study of those years excellent examples of an architecture capable of intelligently combining and take advantage of the “technical, economic and regulatory conditions” that are the “substance, condition and true story of today’s architecture", as Gio Ponti himself says in Domus 234. In other words, it is not a matter of nostalgically admiring a mythical and unrepeatable period of modern architecture – an attitude that would cause more than a little frustration – but of understanding how the young architects of the time were able to combine the regulations, technological innovation and formal quality with a cultured approach, grounded in concreteness and technical knowledge, as the example of Gigi Gho’ teaches us.

For a new ecology of living

Ada Bursi’s legacy is transformed into an exam project of the two-year Interior Design specialist program at IED Turin, unfolding a narrative on contemporary living, between ecology, spatial flexibility, and social awareness.