When writer and music critic Bruno Barilli returned to Belgrade twenty years after his first visit, he found it completely transformed with a grey, monotonous suburbia. Only the Danube River, as seen from the citadel, had remained the same, its wide strip “flashing, becoming shinier and steadier as the great river swallowed the sun”.

Jelena Pančevac, architect at the Brussels-based Office studio, feels the same. Originally from Novi Sad, she studied in the Serbian capital and has been living between Paris and Brussels since 2009. She is very critical of the transformations undergone by the city in recent years, perhaps because its being politically outside of the European Union but certainly not foreign to its culture, has given the city a privileged position as a permeable border.

The new large towers along the Sava River, a major tributary of the Danube, are increasing, turning the shore into a promenade more and more crowded with nightclubs and kiosks. “I think Serbia has been left out of Europe like a big black hole,” says Pančevac, “although not entirely, since the EU accession process is still formally standing, albeit with huge obstacles such as its proximity to the Russian Federation and the unresolved issue of Kosovo”.

“This marginality has made it possible for Serbia to become a land of opportunity for all kinds of unregulated Chinese, Russian and Emirati investments,” Pančevac continues. “It’s terrible because, for example, they freely build on green areas, but all these projects are unregulated and never provide a public infrastructure such as a bridge or anything else”. The architect tells of super-rich people no one knows who go to live in new gated communities, all the expansion areas such as the riverside on the Sava, the airport, the former railway station that have been dubiously cleared. Sometimes a nice place opens up among the railway ruins, but it is the classic gentrification mechanism, the first wave that only benefits developers.

The former central railway station, which was permanently closed in 2018, has become a large pedestrian area linking the upper city centre with the Sava River, but since 2021 an impressive monument to Stefan Nemanja, considered to be the first Serbian monarch, has been erected. Not by chance, the work was made by a Russian sculptor, Alexander Rukavishnikov. President Aleksandar Vucic called it “the most beautiful thing I have ever seen” – a monk holding a sword as he stands on a huge Byzantine helmet housing a golden cup, a “kitsch monstrosity” according to historian Dubravka Stojanovic. Its presence casts a shadow over the beautiful historical station that now houses bars and restaurants.

Certainly the city is full of young people, sporting events, concerts and even floating parties on riverboats, and it is quietly populating with many Ukrainians and even Russians fleeing the war thanks to the fact that there is no need for a residence permit. However, the conflict has rekindled nationalist impulses, banners reading “Kosovo is Serbia” are fixed under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs headquarters (designed by the white Russian architect Nikolaj Krasnov in 1923), and anti-Western resentment over the 1999 NATO bombings is growing again.

If the ruin of the RTS, the Radio Television of Serbia headquarters, has been kept intact since then, there have been many memorial projects in another TV building located a short distance away, in a park overlooking the small “Duško Radović” theatre designed by Ivan Antić between 1963 and 1967. Until recently, along the main pedestrian street in Belgrade, Ulica Knez Mihailova (Prince Mihailo Street), the designs by architecture students for a memorial to the victims of those bombings were on display, proving how that wound is still very much open.

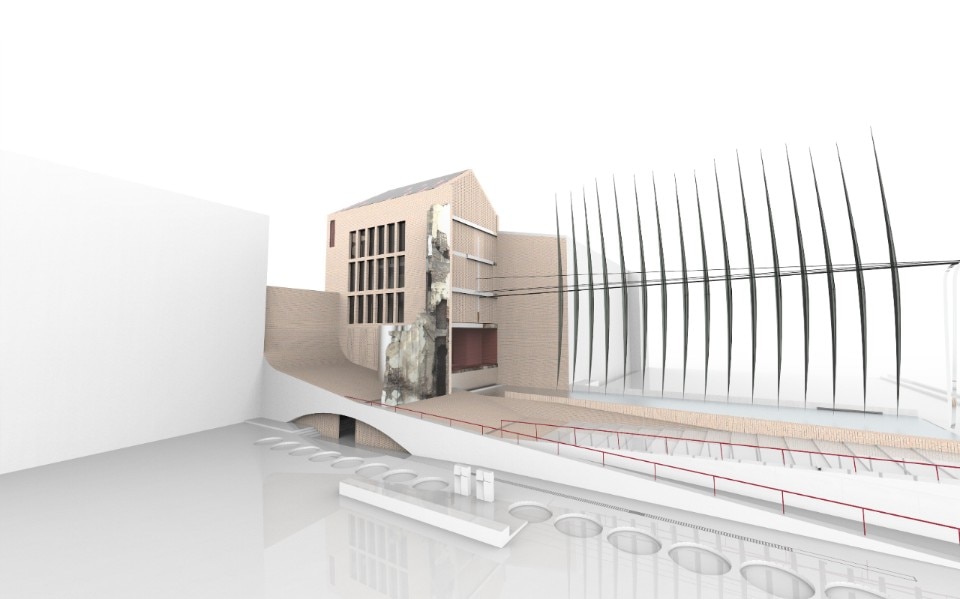

Architect and lecturer Snežana Vesnić recently presented the winning project by his Neoarhitekti studio in the 2013 competition at a conference at the Politecnico di Torino: a kinetic structure made of blades placed on top of a plinth to regulate the area – currently a car park – without blocking the view. The project has been delayed due to a dispute over the ownership of the area between the various entities involved, but the project is in progress and Vesnić’s conceptual references are Italian: Giangiorgio Pasqualotto’s aesthetics of emptiness and Gillo Dorfles’ aesthetics of ruins. According to the architect from Trieste, every time we encounter an architectural testimony from the past, be it a Mayan pyramid or a Greek temple, we cannot but be touched by an irrational note.

The bombed-out building of the RTS headquarters is open, the interiors are visible and the furniture is still there, as in a 1:1 architectural section and, inevitably, a memorial is also a moment of reflection on death. According to Aldo Rossi, “Anyone who remembers European cities after the bombings of the last war retains an image of disemboweled houses where, amid the rubble, fragments of familiar places remained standing, with their colors of faded wall, laundry hanging suspended in the air, barking dogs – the untidy intimacy of places”.

These images of destruction, once so common, testify to “the interrupted destiny of the individual and his often sad and difficult participation in the destiny of the collective”.

It is no coincidence that it was during a return trip from Belgrade in 1971 that Rossi had the opportunity to reflect on death and human bones – which he had fractured in a car accident – as well. Although Neoarhitekti’s project is figuratively distant from Rossi’s imagery, it shares the same theme, demonstrating that it is on the periphery of Europe that the main problems are kept.