Carlo Melograni, aged 97, passed away at his home in Rome last week, with the gentle discretion that distinguished his long life for much of the twentieth century and the first two decades of this.

A militant architect, Professor Emeritus, member of the San Luca Academy, Dean from 1992 to 1997 of the School of Architecture at the new campus of Roma Tre University, and winner of the Architecture Prize awarded by the President of the Republic in 2005, Carlo Melograni - born in 1924 - was a progressive reformer and democratic intellectual, as described by Giorgio Amendola when he recounts his return to the capital in 1943. The young Carlo was actually involved in the Resistance. He enlisted voluntarily in 1944 and for the same reason was awarded the Military Cross. He founded the student seminar named after Giorgio Labò, the student who was murdered by the Nazis in 1944. Giorgio was the son of Mario Labò, an architect and historian from Genoa who was also involved in the renewal of design culture and author of a book on Terragni.

Carlo Melograni's education matured in this climate of civil engagement and militant activism. He enrolled in the Faculty of Architecture in Rome, in Valle Giulia, in the building designed by Enrico Del Debbio, where he met architect Mario Ridolfi and urban planner Michele Valori. At the end of his three-year course he worked for some time in the studio of architect Luigi Piccinato.

His role model was Giuseppe Pagano, whom he considered to be one of the greatest contemporary architects and an undisputed master for his generation of people in their thirties. He dedicated a booklet to Pagano and his work, (aged 31) published in 1955 in Milan by Il Balcone, opened with the following words: “Italian architects do not generally like to recognise among their masters those who are too close to them in time and space. We prefer to dedicate our sympathy to someone we are separated from by a border or an ocean, or several decades of history”.

This was the homage the young Roman architect paid to someone he considered to be a moral and civil role model even more than an architectural one, even though there were neither the distance of an ocean nor several decades of history between them to nurture the myth. Pagano's influence had the beneficial effect of discouraging any form of personal poetics and of encouraging him to “take it out on those who have the ambition to become leaders in the field with some unexpected and unthinkable invention”.

Firmly rooted in the tradition of functionalist rationalism, confident in architecture's ability to become an instrument for the redemption of all forms of spatial injustice, Carlo Melograni was a strong and constant promotor of an idea of modernity conceived as the patient search for a collective work. In fact, he always worked with others, in projects, in field research and in teaching.

From 1961 to 1971 he worked with architectural historian Leonardo Benevolo and architect Tommaso Giura Longo, with whom he wrote I modelli di progettazione della città moderna - Tre lezioni, a reference book for several generations of students.

In 1981 he founded the studio "P+R, Architectural Projects and Research” with Marta Calzolaretti, Piero Ostilio Rossi, Ranieri Valli and Andrea Vidotto, younger colleagues at the university where he taught. All their project and research activities were addressed to public bodies and institutions: schools and public housing were the main themes of their design explorations. Two significant issues of Edilizia Popolare from 1979/80 deal with the themes of residential buildings with a suspended bridge and low and high density housing. The group's references ranged from Robin Hood Gardens to the Matteotti Village, from the northern European architecture to the Smithson’s and De Carlo’s Team X, and the Dutch school of Aldo Van Eyck and Herman Hertzberger.

In 1989, the magazine Parametro dedicated a special issue to the design research of Studio “P+R, Architectural Projects and Research”.

It covered some thirty projects, both competitions and works, carried out over ten years of activity, in which we find remarkable coherence between the declarations of principle and the completed projects. They include innovative residential models for new residential proposals, small-scale restoration projects in archaeological sites, an intermediate scale between plan and project, and architetture di pecorso.

In the study of new building types for Sabaudia in 1985, for example, they proposed a fabric of patio houses and different types of single-family houses on top of each other, where the residential unit could be disassembled into its various components and re-assembled according to various combinations to meet the new needs of the inhabitants.

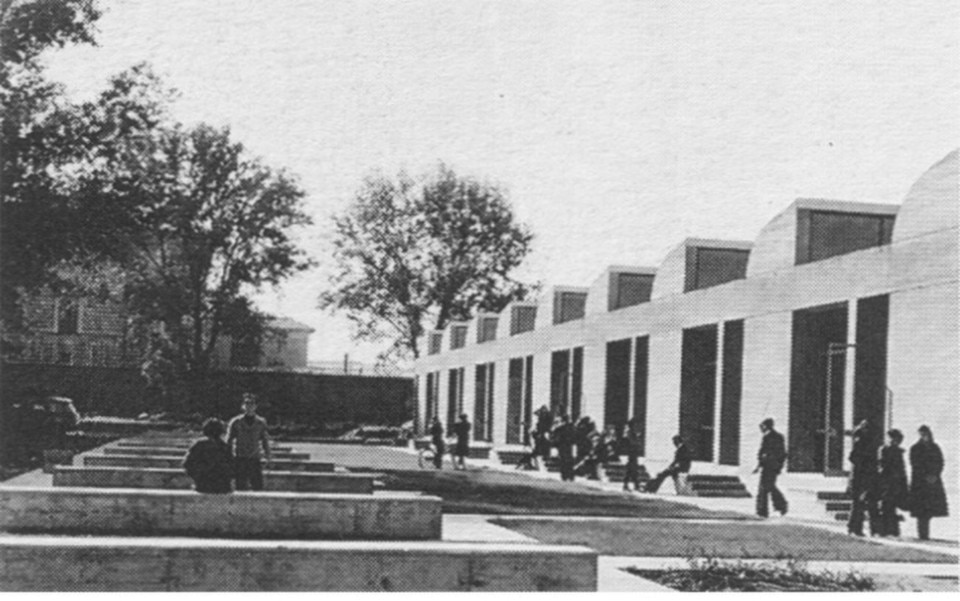

In their “architetture di percorso”, on the other hand, mainly projects for schools and research centres, the functional layout was the result of a circulation model that connected the different parts of the whole - creating an open system - and provided spatial structures that could be adapted and added to over time. In both cases, as in the case of the Ariosto high school extension in Ferrara, the overall fabric is more important than the singularity of the building, and the overall quality is more important than self-referential architecture.

The aim was to encourage relational behaviour between individuals, as we read in the project reports. There was a close affinity with northern European, and particularly Dutch, rational architecture, but also with the Smithson's “structures of the anonymous collective”. The idea of anti-authoritarian architecture for a democratic model of the city was both their manifesto and their legacy.

Melograni was, of course, a master, without intending to be one nor presenting himself as such, neither with his students nor with employees or partners he shared his projects and research with. He stood firmly and consistently by his beliefs, considered by some to be rigid, little inclined to bend in the face of the tsunami of post-modernity, and considered by others to be the necessary breakwater in the face of such a storm.

Melograni remained until the end an advocate of a functionalism understood not “as a fallback, but as a goal”, and of an authentic modernity capable of “opening the doors to the outside world” and welcoming the different voices from collective research, against the risk of an aggressive and self-referential modernisation.

- Opening image :

- Carlo Melograni in London in 1974 traveling with students, on the hill between the houses of Robin Hood Gardens, designed by Alison and Peter Smithson