It sounds like a paradox. Yet in the era of manufacturing that we hear is ending, replaced by the service economy and experiences, many millennials are betting on industrial design. They believe in the factory, in technical artisanship, in the entrepreneur-type of designer, even now that the pandemic has brought businesses to a halt and is calling for a rewriting of the rules. Does this sound familiar? It is. It’s the same modus operandi followed by the generations preceding them. What has changed, and radically so, is the way things are produced and the market that traditionally was the design segment. Selling the added value of design has become difficult since the word is often confused with decoration. Thanks to digital communication, being noticed by companies is within everyone’s reach, but convincing them to invest in your budding talent is almost impossible. When they do invest, most producers – struggling to thrive, or managed by funds – play it safe by engaging names that are sure to bring in business, preferably of the contract type.

Working as an industrial designer for the manufacturing industry today is not only tough, but risky too. For young people, earning enough money to survive on royalties has become even more improbable than than it already was.

So why are many people under 40 – who have grown up in a digital world, have a global outlook, and are bombarded by the success stories of celebrity designers whose bread and butter is interiors, fashion accessories, and home décor – choosing the more complicated, less profitable, unglamorous road of the profession: industrial design?

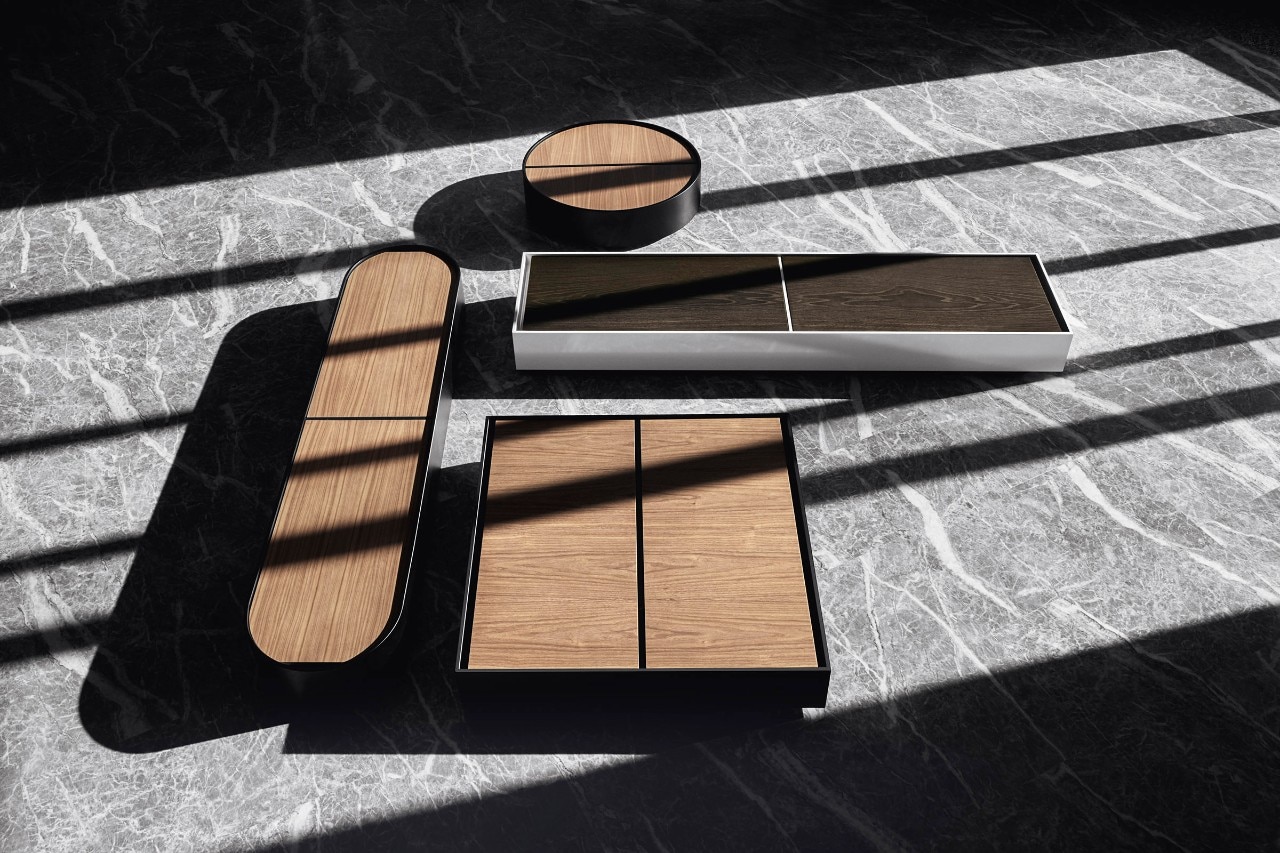

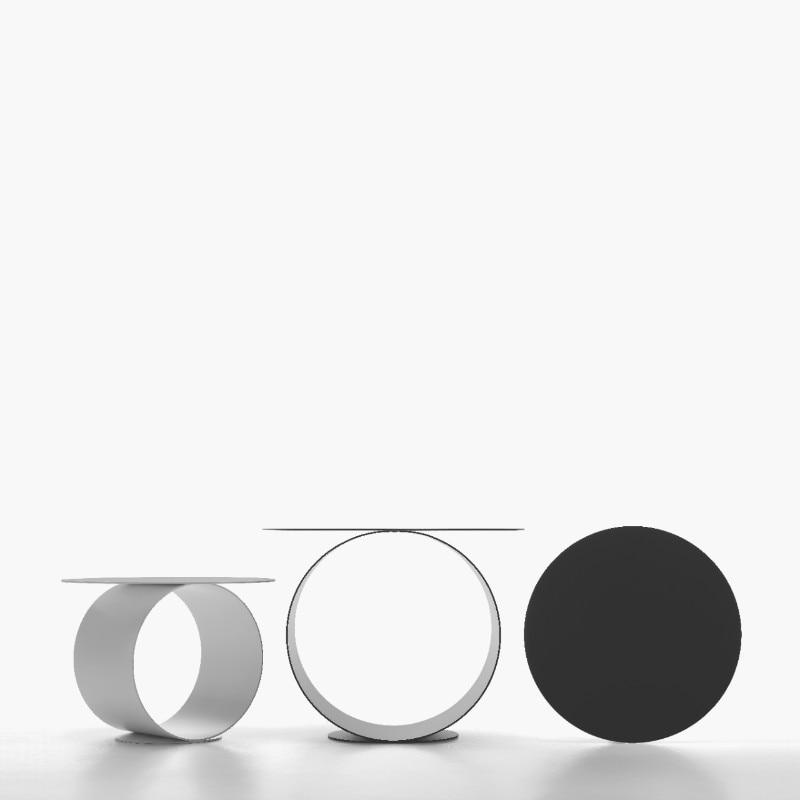

“For us, it was a kind of vocation, in the sense that we came together professionally thanks to our shared keenness for understanding how things are made,” say Alberto Brogliato (1981) and Federico Traverso (1978), the duo behind the Lost lamp (2019) for Magis, which emits light from the external surface of a cylinder, and is turned on by placing your hand inside the central hollow. After graduating in architecture from the Iuav in Venice, the two spent their time learning how glass is blown in Murano, how ceramics are made in Japan and how wood is crafted in the region of Friuli.

“It wasn’t until then that we understood that design consisted in a project and not in a style, a process of questions and answers that leads to solving problems, and a product configuration that is right for the brand, the manufacturer and the user. So it’s a discipline that covers the entire system, not just a serially made object, which is why industrial design is based on innovation of all types, and teamwork. In light of our experience until now, we can say that good products are made with companies, not for companies.” This is the so-called “Italian design system” where entrepreneurs, technicians and designers work together on the development of the projects.

A form of collaboration in which human contact plays an important role. The change in dynamics caused by the Coronavirus could change its very nature. “It is relationships and creative empathy that gets projects off the ground, aspects that are essential”, claims Federico, convinced that these elements will not be lost in the manufacturing fabric made up of artisans and small-scale businesspeople from the Po Valley, where distances are limited and businesses are small, making it possible to work quickly and in compliance with social distancing. It could even be that the setup of out manufacturing structure proves to be a winning model. “I hope to see changes on other fronts, which lead to the creation of new forms of furnishing, releasing the home office from the constraints of a marketing department slogan that have characterised it until now, or solid investments into research for sustainable and recyclable materials”, he continues, “even though I believe that the most sustainable measure is to create objects that are made to last”.

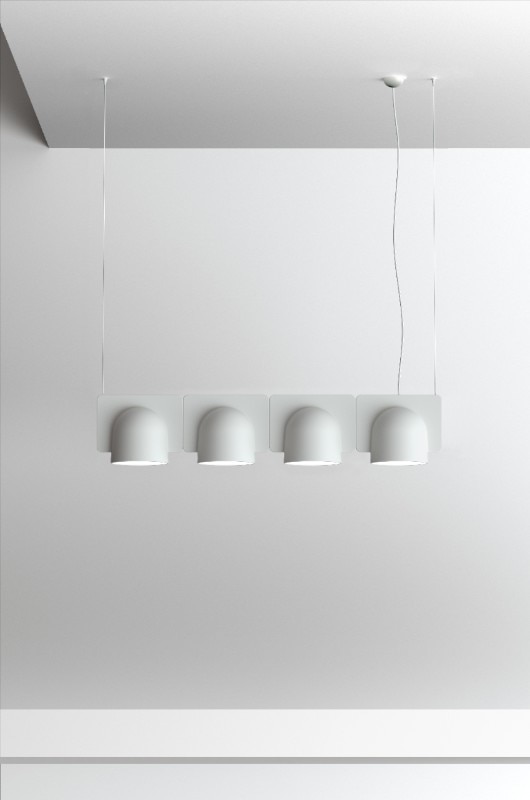

It is a formula that we hope manages to survive the scenario created by the pandemic, but which is undoubtedly evolving. What has changed over the last few years? “Many things have changed,” says Marco Maturo (1985) from Studio Klass. “But I see many representatives of our generation who are closer to this way of working than to the approaches that concern styling, name branding and convenience-based collaborations.” Maturo and his associate Alessio Roscini (1983) look to the subject matter and methods followed throughout the history of Italian design. “This includes combining technology and technique with shapes, materials and functions, as seen with Alberto Meda; design that becomes part of our habits and supports them or creates new ones, as seen with the Castiglioni brothers; and the revolutionising of products and types of products one small step at a time with inventions that are not ostentatious but nonetheless fundamental, as seen Antonio Citterio’s work with upholstered furniture. Our generation brings to industrial design today the advantages of our times. It mixes all these factors, which are necessary for a project to be relevant in a universe where everything already exists.” This principle is found in their Touch Down Unit, an independent mobile workstation for UniFor that was awarded the 2020 iF Design Award. It is definitely technical (a gear-wheel mechanism allows for the desk’s reconfiguration without needing batteries), but also humanistic in the way it responds to new ways of living and working (it is conceived to give spatial dignity to the freelance consultants employed by corporations).

Maturo defines the blending of different approaches as “design schizophrenia”. “It’s normal for us to be ‘soft’ when we design a rug for CC Tapis, rigorous when we work on a table for Fiam, and show a sense of humour when we make a stool for Cantarutti. What counts is the coherence of the way you approach the subject matter, not the end form. It’s like Spotify – you listen to a bit of everything, but each listener has a personal denominator in selecting the songs,” he says.

This ability to adapt a design approach to different items and contexts is very valuable now that our way of living and working has been shaken up by Covid-19, with consequential effects on the places and objects that we use, as well as on forms of behaviour to be adopted. “The first thing to be done is to rethink domestic spaces, and therefore furniture, in order to be able to live and work in the same spaces”, stresses Maturo. “And who knows, maybe the attention that this pandemic is focusing on the precarious nature of available resources, the effects of pollution and of climate change will change the approach to purchases on a collective level, leading to the selecting of quality products that are engineered with criteria of sustainability and are built to last, thus proving to be twice as sustainable”. Studio Klauss also feels that the Italian manufacturing system is confirming its worth, although extra efforts are required in terms of strengthening the network of contacts, improving the sharing and circulation of skills, a passage that is more important than ever now that the search for materials and resources beyond national borders is particularly problematic. “The moment has come for the creation of a network of suppliers of mechanical, electrical and semi-finished products…”, he sums up pragmatically.

Another characteristic of the under-40 group of Italian industrial designers is their business savvy. They believe in themselves from day one. See their websites only in English, and their practices founded at a very young age without having apprenticed with the masters (something that was de rigueur with the past generation).

Leonardo Talarico (1988) is one example. Since he was 23, he has been working for companies of the calibre of Cappellini, MDF Italia and Living Divani, with a sideline in fashion at Tod’s. “Every generation has the duty to make the discipline progress, and the way to do that is to stick your neck out,” says Talarico. “While the ‘historical’ generation of the Castiglionis, Vico Magistretti and Ettore Sottsass gave life to the phenomenon of Italian design, and the generation after (Citterio, Piero Lissoni and Rodolfo Dordoni) introduced it to the world, it’s our task to take a step further.” What step might that be? “It’s not yet clear to me, but to get an idea I look around, not behind me. I see that the problem design has today is sales, and getting away from what is already out there in terms of projects and distribution methods. I see designers becoming successful brands by entering parallel worlds like restaurants and cafes. Our job as a generation is perhaps finding another road that works. When we work for companies, we cannot allow ourselves to just design without looking at costs, manufacturing difficulties, and prototyping. We might feel sorry for ourselves and say how daunting all this is, but I see our generation as a lucky one. We grew up without the towering presence of the old maestri above us, which was the situation of today’s designers in their fifties. We have a lot more chance to become known abroad, because people like Lissoni, Citterio and Dordoni opened that door for us. I do not think this is a bad moment to be doing industrial design, as long as you work with ethics and aesthetics. We need to pass from cute things to beautiful things that are born to stay with us forever. I mean simple objects that are not part of a trend, that rouse interest and attachment thanks to small, unusual details. I don’t mean the ‘let’s make it outrageous’ type of junk design, but an added feeling that rationally and emotionally appeals to people who enjoy the sophisticated simplicity of good design.”

This view of his of the ingredients for ‘correct’ design has not changed in light of the virus. “What will change is the wishes of people and the solutions that we designers will be able to provide”, he continues. “We need to adapt to situations, learning to take advantage of them. We also need to improve the quality of objects, producing only that which is really necessary, making use of an entire supply chain that works in a sustainable manner”. Are these unrealistic concepts destined to remain good intentions? “We need to begin with an analysis of the new habits that are emerging. There is undoubtedly an increased focus on hygiene, which we will carry forward even when the virus no longer poses a threat. Studies can be made in this direction, something that I am already doing. Work can be concentrated on materials and finishes – even simply revisiting old collections with new types of paint – and on the multi-functional aspect of objects, providing a boost to the home-office concept, which has been expanding for some time now”. Small ideas with specific functions. Less quantity, more quality; a point at which the paths of all these enthusiastic under-40s converge perfectly.