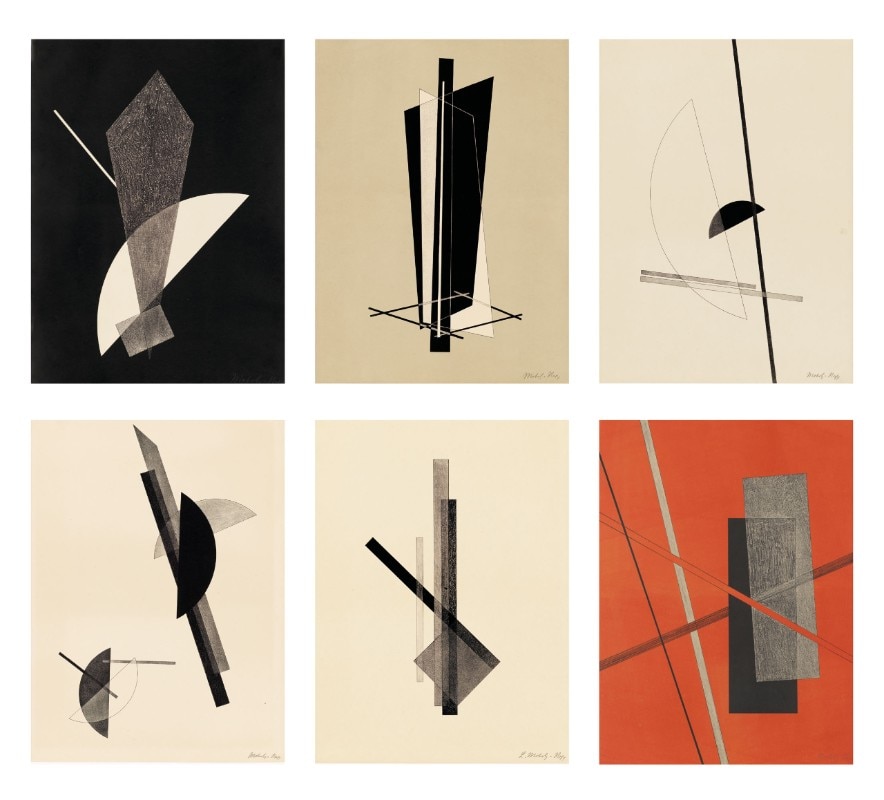

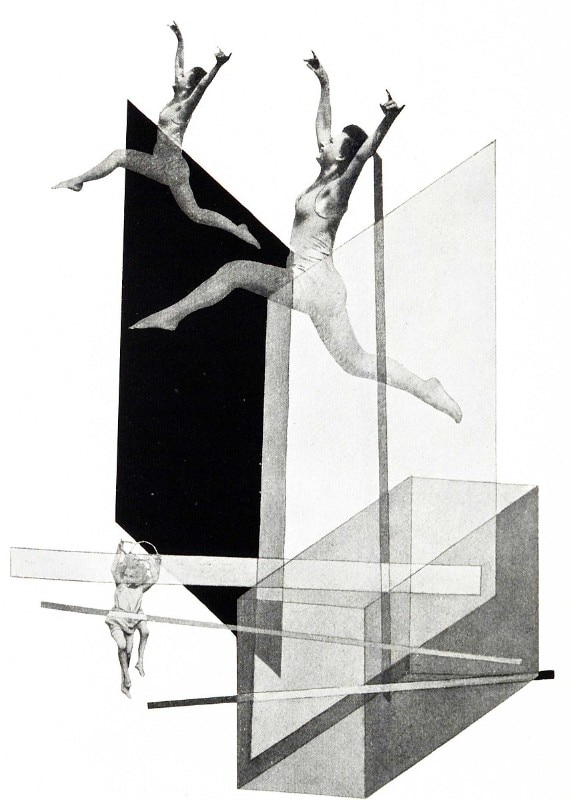

Intrepid, generous and subversive, László Moholy-Nagy is one of my favourite characters in design history. Who could resist the Hungarian artist and intellectual that wore a factory boiler suit to signify his zest for technology while teaching at the Bauhaus in the 1920s, when he allowed women to study whatever they wished, including subjects previously reserved for men? After moving to the US in 1937, he was equally courageous in welcoming African Americans to his Chicago design schools when the city’s education system was largely segregated.

Moholy-Nagy also championed an unusually eclectic and enlightened vision of design that liberated it from the constraints of the commercial role it had occupied since the Industrial Revolution by redefining it as an improvisational medium rooted in instinct, ingenuity, resourcefulness and open to everyone. He summed this up in Vision in Motion, published in 1947 a year after his death, with the phrase: “Designing is not a profession but an attitude.” Those words sum up the new spirit of design at a thrilling, yet intensely challenging time when the discipline is changing dramatically.

Design has adopted different meanings at different times and contexts. Yet it has always had one role as an agent of change that helps us to interpret changes of any type - social, political, economic, scientific, technological, cultural, ecological, or whatever - to ensure that they affect us positively, not negatively.

We need its power right now as we face profound changes on so many fronts and we discover that many of the systems and institutions, which regulated our lives in the last century, are unfit for purpose. Design is not a panacea for any of these problems, but it is a useful tool to help us to tackle them, if it is applied intelligently. Designers have long grumbled about being denied the chance to do so because of the stereotyping of their discipline as a styling or promotional tool. Will the outcome be different this time? It might.

One reason for optimism is the sheer scale and complexity of the mess we’re in, and the mounting concern that many of the traditional solutions are redundant. Hilary Cottam, the British social scientist who has emerged as a doughty pioneer of social design, is convinced that this crisis of confidence has made economists, politicians and her fellow social scientists readier to experiment with new methodologies, including design, when restructuring health care services or planning disaster relief programs. The same applies to the growing number of businesses, which are deploying design to help them to operate more responsibly in response to pressure from the public and their employees. Another factor is the transformation of the practice and possibilities of design thanks to the availability of inexpensive digital tools.

Designers can now raise capital from crowdfunding and manage huge quantities of complex data on affordable computers. They can use social media to flush out collaborators, suppliers and fabricators, to generate media coverage and to secure more funding. Individually, each of these technologies would have had an influence on design, as they have on other fields, but collectively they have proved metamorphic, by enabling designers to operate independently and to pursue their own social, political and environmental goals in Moholy-Nagy’s attitudinal spirit, rather than working under instruction from others.

Take one of the boldest independent design projects of recent years, the Ocean Cleanup, a Dutch non-profit that aims to clear plastic trash from the oceans. It was founded in 2013 by a design engineering student Boyan Slat, who raised over $40 million in five years to complete the design, prototyping and testing of a gigantic floating structure that, he believes, will crack the problem. Not everyone agreed. Ecologists warned that Slat’s plans could damage marine life, scientists claimed they wouldn’t work and some designers dismissed him as a mediagenic opportunist. The Ocean Clean Up rig went live in the Pacific Great Garbage Patch in autumn 2018, only to be towed back to San Francisco a few weeks later for repairs and further tests. It returned to the Great Garbage Patch a year later and functioned efficiently.

The Ocean Cleanup fulfils Moholy-Nagy’s vision of designers working in close collaboration with specialists from other spheres. He also expected the reverse to happen and for experts from those fields to experiment with design, as Cottam has done.

Equally impressive are the Pakistani doctors, Sara Khurram and Iffat Zafar, who have used their instinctive design ingenuity to develop Sehat Kahani, a network of tele-clinics where women throughout Pakistan can be diagnosed remotely by female doctors, who are working in their homes hundreds of miles away.

Design has not traditionally been seen as an obvious solution to health care shortages and dysfunctional social services. Nor were independent designers expected to raise tens of millions of dollars to mount epic ecological ventures. Even now, more people are likely to perceive it as a reason why our oceans are clogged with plastic trash, than as a means of clearing it away. These stereotypes will only be quashed, if the ambitious new genre of design projects prove their worth.

Design will not win the trust of other professions unless it is applied wisely and sensitively, and so designers must be ready to forge true collaborations with other specialists rather than treat them as a new business. One priority is for designers to be readier to forge true collaborations with other specialists and to treat them as opportunities to learn, rather than to bag new business. Another is for the design community to become more diverse and inclusive.

We need the best possible designers to be drawn from every area of society, not just the white cis-males who fill design history books. Finally, designers must accept that if their work becomes more ambitious the consequences of failure will escalate. Just as every thoughtfully planned and executed design project represents a step forward, each sloppily designed flop will make it much, much harder for design to fulfill its potential.

Alice Rawsthorn is an award-winning design critic. A new edition of her book Design as an Attitude will be published in February 2020.