Carlo Rambaldi was regarded as an undisputed master of cinematic animatronics—an artist who understood special effects as expressive tools rather than mere technical innovations. In an era when television was accelerating and cinema was chasing increasingly complex narrative forms, his creative and formative path remains a singular case: a rare crossing that united auteur-driven Italian cinema with major Hollywood productions under the banner of sculptural mastery and mechanical engineering.

On the centenary of his birth, the Museum of Modern Art in New York honours him with a major retrospective organised with Cinecittà and supported by the Italian Ministry of Culture. The program features fifteen films spanning Rambaldi’s entire career, from restored Italian titles such as Deep Red, Check to the Queen, Frankenstein ’80, and The Canterbury Tales, to the American productions that earned him three Academy Awards for King Kong, Alien, and E.T.

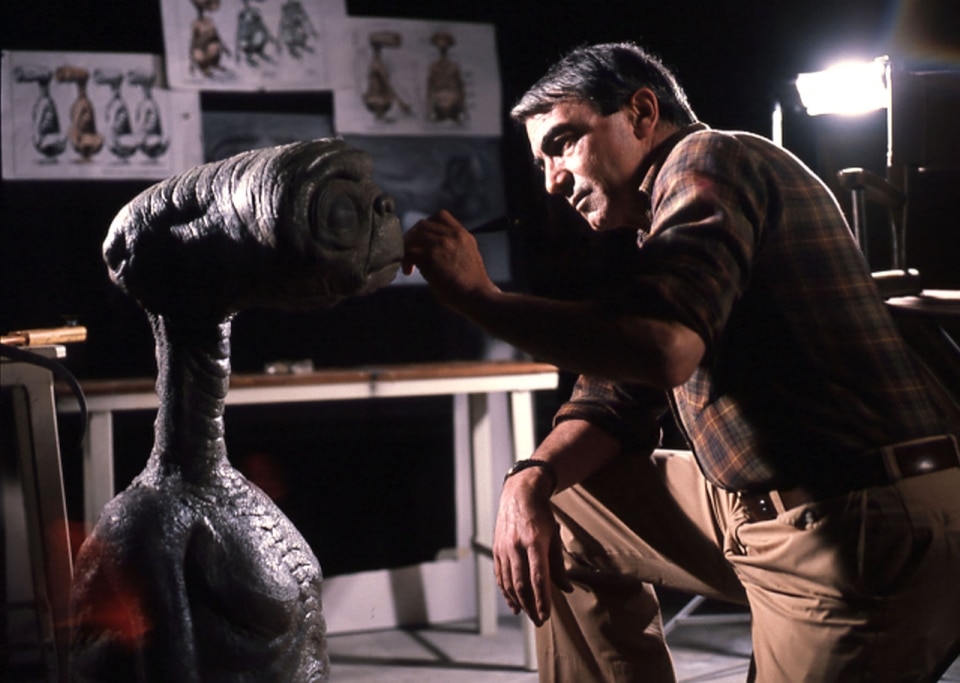

If movies are the realm of magic, then effects artists are the magicians. From a 40-foot Kong to blood-splattered horrors, to the kindest alien ever to visit earthly screens, Carlo Rambaldi created and built characters that will live on forever in cinematic history

Rajendra Roy

"Carlo Rambaldi" seeks to reconstruct the threads of an intrinsically artistic approach, one in which technique and imagination advance side by side to bring new forms of realism to the screen. The New York retrospective, curated by Rajendra Roy, follows this trajectory, presenting an uninterrupted dialogue between the two worlds—geographical and cultural—that Rambaldi navigated with ease.

His artisanal vocation had deep roots in his early passion for drawing and sculpture, later cultivated at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna, where encounters with painting and the European avant-gardes—from Picasso to Morandi—helped him refine a gaze suspended between figuration and invention. After an early experience on Giacomo Gentilomo’s Sigfrido, for which he built a sixteen-meter dragon, Rambaldi moved to Rome. It was there, in his so-called “monster workshop,” that he began shaping the unprecedented body of work that led to collaborations with Mario Monicelli, Dario Argento, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Marco Ferreri, and Luchino Visconti. His special effects and animatronic systems were so realistic that in 1971 he was required to testify before a judge that the dog vivisection scene in Lucio Fulci’s Una lucertola con la pelle di donna was artificial, thus preventing the director from being charged with animal cruelty.

By the mid-1970s, Rambaldi’s move to Hollywood brought him to create monumental and unsettling creatures that redefined the language of science fiction, opening a new chapter in the cinematic imagination: from the sandworms of David Lynch's Dune to the empathy embodied by E.T., Rambaldi’s touch remains unmistakable in the conviction that even an invented form must move according to an internal logic—credible, coherent, alive. A legacy that continues to shape international cinema and that, still today, retains its full inventive force.