With the tenth anniversary of the death of Umberto Eco on February 19, 2026, the embargo-anathema imposed by the Italian prophet of semiotics on his own memory comes to an end. In his will, he had asked that for ten years no public events be dedicated to his work or his person. A reasonable request, perhaps, for one of the most quoted authors of the late twentieth century and the new millennium.

And while the fateful date brings with it a YouTube marathon of tributes long held back, we couldn’t help but wonder whether a dive into Domus digital archive might add a few tesserae to the story.

It does – and more than a few – both to the narrative of a reputation and to the ongoing push and pull between designers and philosophers. Eco belongs to that group of thinkers – arguably even more frequently quoted – whose paths crossed architecture, design, and space more than once. Think of Michel Foucault and the prison panopticon as the materialization of control, or Jacques Derrida and a term that became both a philosophical and architectural current: deconstructivism.

Eco stands among them, though rather than a mere “quote generator”, he often assumes the role of legitimizing father, whether to be praised or symbolically slain, as the members of Italian radical design group UFO would metaphorically and Freudianly attempt (a truly twentieth-century story).

Eco, rather than a mere ‘quote generator’, often assumes the role of legitimizing father.

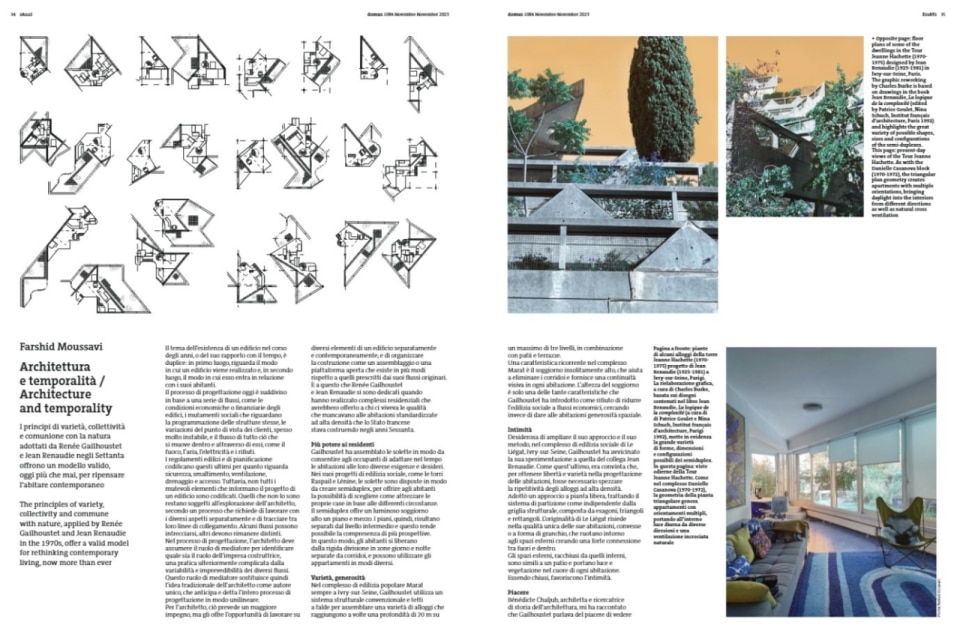

Opera Aperta (The open work) is the text most cited in recent years on Domus, invoked by Anne Holtrop, by Farshid Moussavi when discussing Renée Gailhoustet’s structuralist design. But it was Apocalittici e integrati (1964) that became the real mot de passe of the late 1960s and the long Italian postmodern era.

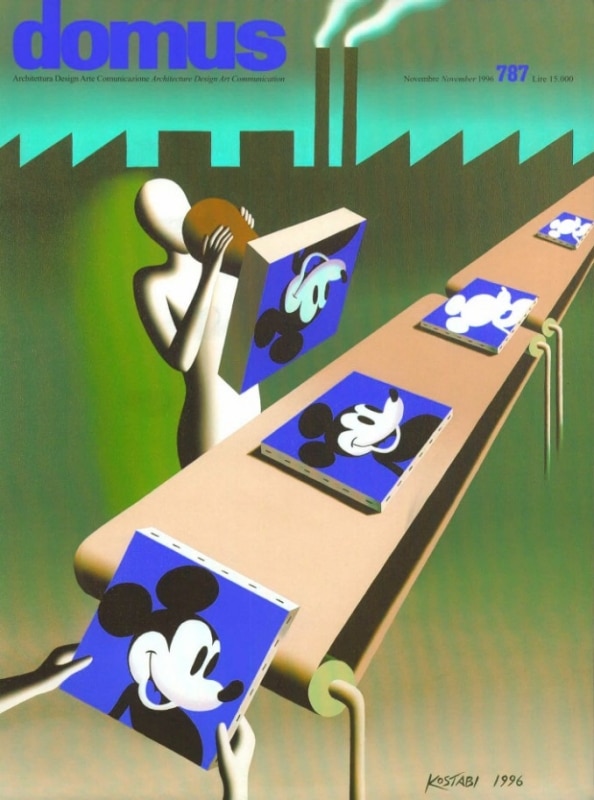

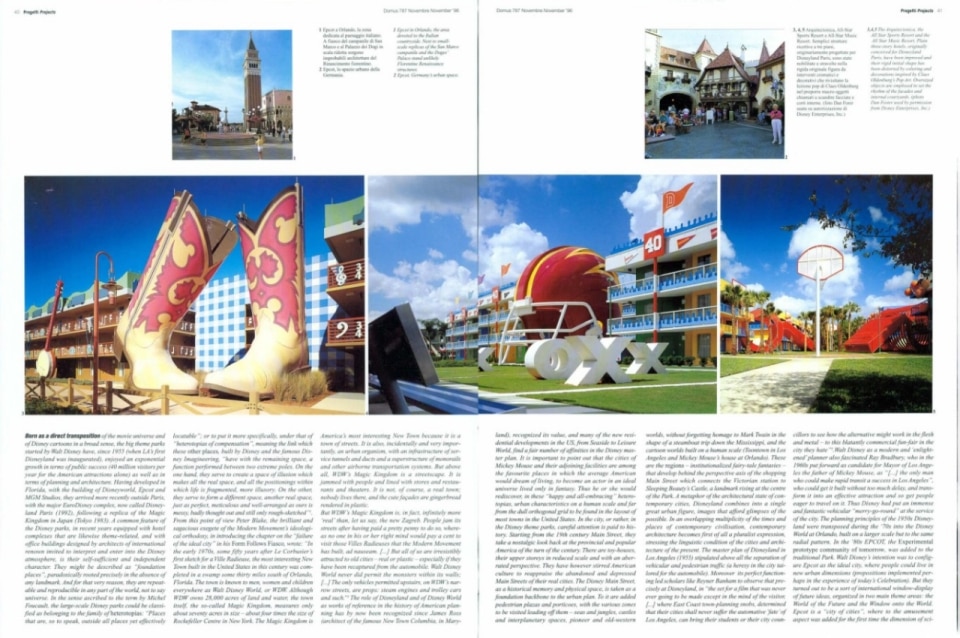

Then come spectacle, advertising, the total vaporization of boundaries between reality and fantasy through the language of consumerism: “Disneyland makes it clear that within its magical enclosure fantasy is absolutely reproduced, in a world more real than the real”. Here is Eco, quoted exactly where one might expect, in Domus issue no. 787 (November 1996), edited by François Burkhardt and devoted to the “Disney syndrome”, to the Disney linguistic galaxy as an agent transforming our living space, including through the architecture with which we fill it. The story unfolds through buildings by Frank Gehry, Arata Isozaki, Robert A. M. Stern, and the duo Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown.

After all, we are speaking of someone who traversed the society of spectacle from within and helped shape it: a young “corsair” entering Rai in the early 1950s to bring semantic shifts to the first television broadcasts, launched from Milan in 1954 – where Domus returned, there, to the Gio Ponti-designed Rai building on Corso Sempione, to celebrate seventy years of Italian TV. He also authored questions for the legendary quiz show Lascia o raddoppia?

We are speaking of someone who later deconstructed, reconstructed, and often treated that very society with irony, from Diario minimo to Fenomenologia di Mike Bongiorno. Someone who engaged above all with its tensions and questions, in an industrial postwar Italy serving a cocksure face full of certainties, yet already foreshadowing total disorientation.

Disneyland makes it clear that within its magical enclosure fantasy is absolutely reproduced, in a world more real than the real.

Umberto Eco

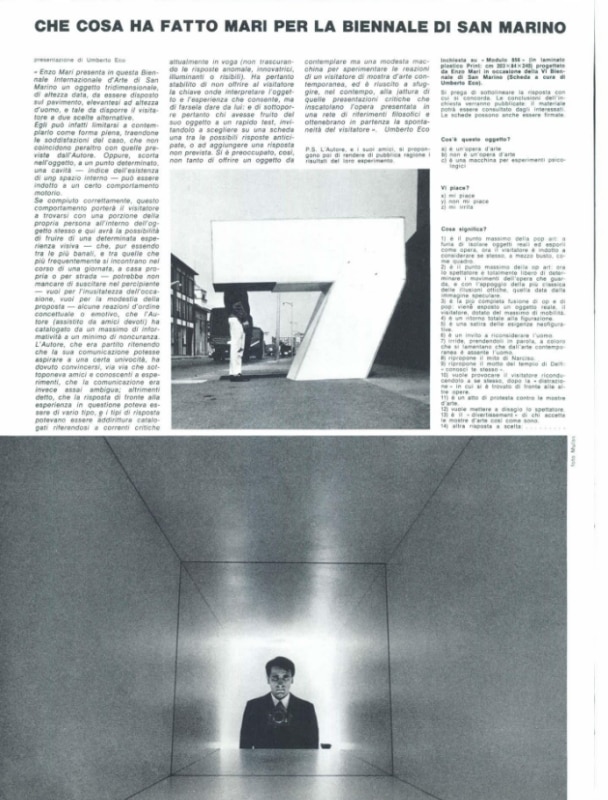

The Umberto Eco introducing Enzo Mari for his 1967 work at the San Marino Biennale is also the only Umberto Eco we see speaking directly in the pages of Domus, and it takes the form of a survey, a poll. “The Author, who had initially believed his communication might aspire to a certain univocality, gradually had to convince himself, as he subjected friends and acquaintances to experiments, (…) that responses to the experience in question could vary widely, and that types of response could even be catalogued according to critical currents now in vogue (not neglecting anomalous, innovative, illuminating, or laughable answers)”.

The floor is given to the public, with questions such as: “What does (this work) mean? (…) 8) It re-proposes the myth of Narcissus. 9) It re-proposes the motto of the Temple of Delphi: ‘Know thyself.’ 10) It seeks to provoke the visitor by leading them back to themselves, after the ‘distraction’ experienced before other works. 11) It is an act of protest against art exhibitions. 12) It aims to unsettle the viewer. 13) It is the ‘divertissement’ of someone who accepts art exhibitions as they are. 14) Other answer: …”

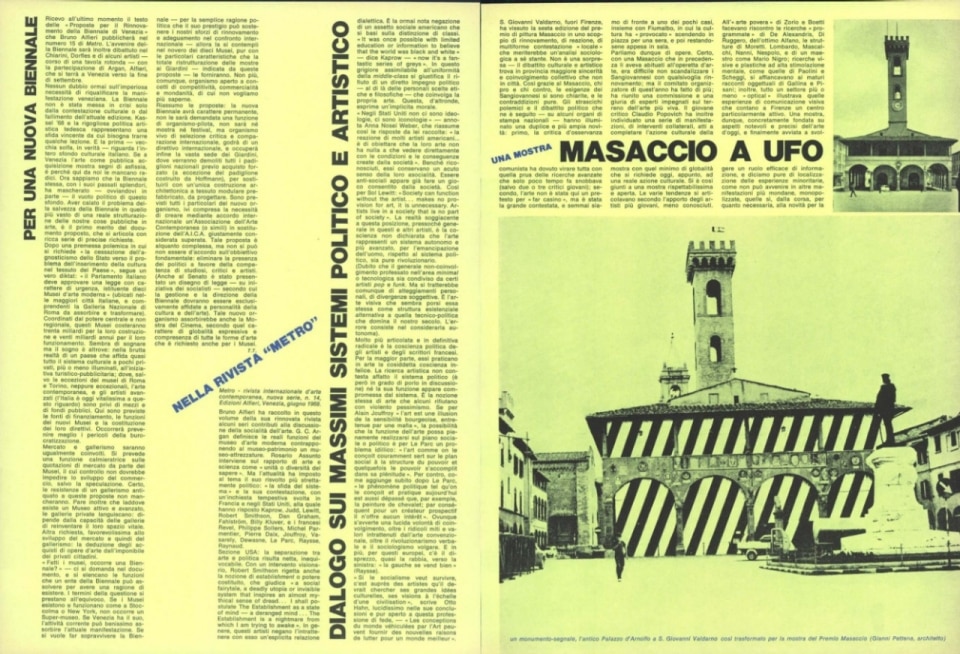

As Italy is perceived as a vast province unto itself, Eco travels through it, and Domus follows him, into every pop-up, even the ones that more are more boiling with harsh debate, where the philosopher plays a central role. As in the provocations of the radical Florentine group UFO, who in 1967 hacked the Masaccio Prize in San Giovanni Valdarno and “unleashed” – or hosted – debates coordinated by Eco himself. Evolutions would also include separations, like UFO themselves would do a few years later, distancing their stance from Eco the Freudian father (despite rebranding him as “uncle”).

After all, we are speaking of someone who traversed the society of spectacle from within and helped shape it.

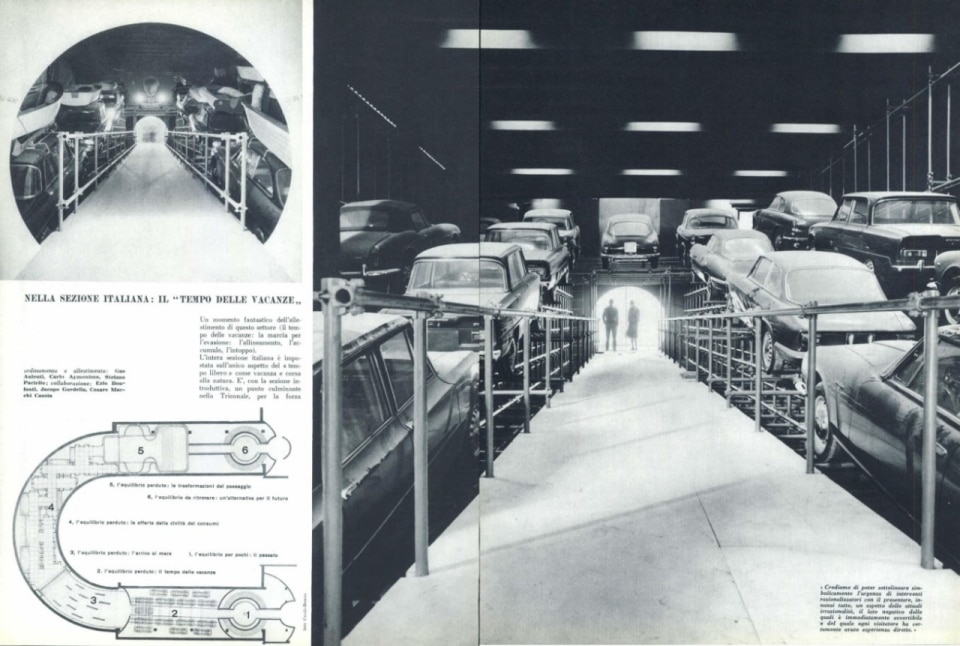

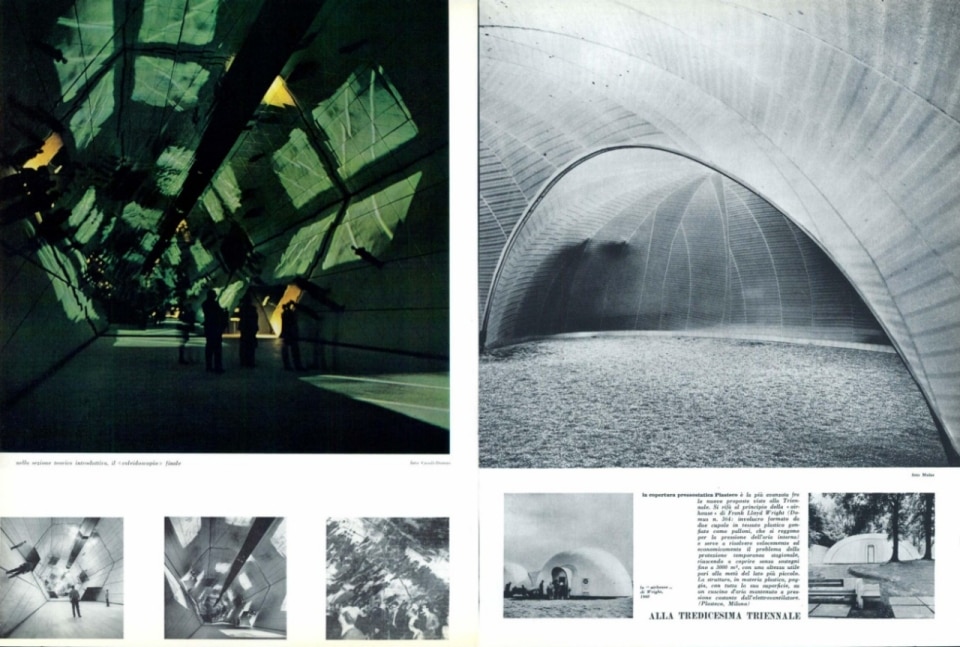

Then comes a node tying many of these paths together in Milan’s Parco Sempione, not far from the house that used to host Eco’s affinity-ordered library: this node is the Palazzo dell’Arte. There, Eco and Vittorio Gregotti curated the introduction to the XIII Triennale in 1964, the last episode in a cycle that would effectively close with the following, the 1968 edition stormed by protestors at its opening. In such modernist swan song, the subject was leisure time. Gae Aulenti welcomed visitors with the figures of her Arrivo al mare. The dream team of Italian design was present in full force: Franco Albini and Franca Helg, Joe Colombo, Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper, to name a few. And surrounded by all this were the experimental short films of a barely thirty-year-old Tinto Brass.

What might the philosopher who shaped the very society he later scrutinized say about this renewed flood of discourse calling him into play, especially after having been both its endpoint and its beginning with his decade-long edict of silence? And what about being invoked in recent architectural history both to legitimize in-deep interpretations of design and spatiality, or reflections on the role of interior claddings? It can only be a speculative divertissement. Yet, finally allowing ourselves to quote Umberto Eco – this time as the author of Diario minimo – one is tempted to conclude: “Such is the fortune of parody: it must never fear exaggeration. If it hits the mark, it will merely prefigure something that others will later do with no laughing, and no blushing, with firm and virile seriousness”.