by Luca Avigo

“Capitalism's victory has not consisted in it confidently claiming the future, but in denying that the future is possible. All we can expect, we have been led to believe, is more of the same — but on higher resolution screens with faster connections.” It is perhaps precisely because of this prophecy by Mark Fisher that, since his premature death in 2017 at the age of 48, the world has become increasingly Fisherian.

In fewer than twenty years of acute and relentless cultural criticism, Fisher theorised the impossibility of imagining systemic alternatives, depression as a condition “collective deliberately cultivated by power” rather than a private pathology, the normalisation of precarity, and nostalgia as the dominant cultural form. These elements appear to consolidate year after year, despite — or perhaps precisely through — ruptures such as the pandemic or the advent of artificial intelligence. We live, in his words, in a “crashed present”, a present “littered with the ideological rubble of failed projects”.

It is therefore unsurprising that, in the years following his death, the reception of his work “has exploded. So many of his works have been translated into many other languages, and the PDF circulate with ever greater intensity,” Macon Holt, his former PhD student and now lecturer and author of Pop Music and Hip Ennui. A Sonic Fiction of Capitalist Realism, tells me. According to Gianluca Didino, author of the Italian afterword to The Weird and the Eerie, Fisher “è stato santificato (e forse martirizzato) molto in fretta: dopo la morte è diventato rapidamente pop. Oggi è un riferimento quasi dato per scontato”. Domus itself has cited him several times: in 2022 on Moon Boots and the stratification of revivals, in 2023 on the chaos of open-plan offices, and two months ago on the latest proliferation of vampire films.

Mark had a capacity to see things clearly and seeing things clearly can bring anyone to despair.

Simon Reynolds

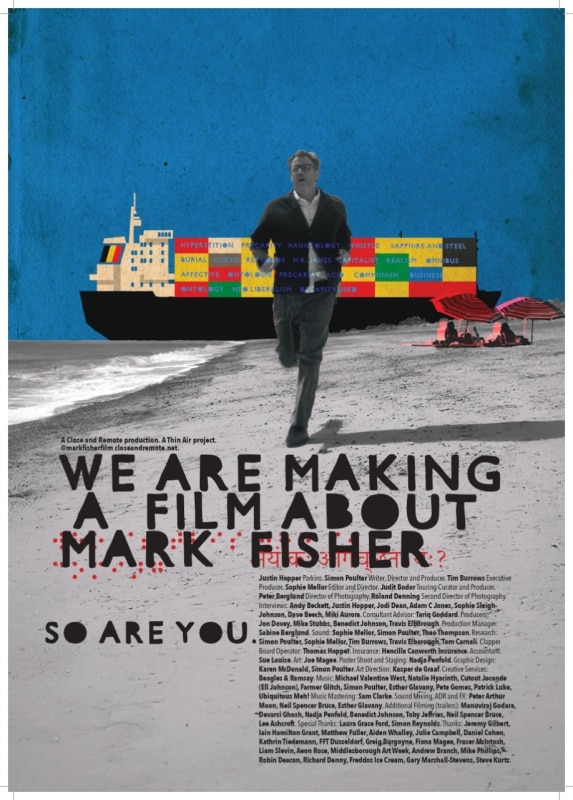

The most recent manifestation of this phenomenon is the documentary We Are Making a Film About Mark Fisher, made by Sophie Mellor and Simon Poulter “with no budget, no studio backing and no institutional permissions”. For Holt the film is “super impressive”; Didino has not yet seen it, but tells me that “mi ha fatto ridere che il trailer inizi nel tunnel che percorro ogni giorno in bici per andare al lavoro, e non è un luogo così distopico come sembra”. Mattie Colquhoun, editor of the Postcapitalist Desire Lectures and author of Egress: On Mourning, Melancholy and Mark Fisher, explains how “The idea of a film-in-progress, shared and adapted across social media, is novel, and it speaks to Fisher's sensibilities as a blogger.” Simon Reynolds, the legendary music critic and fellow traveller since the K-Punk years, adds that “Mark would have appreciated that the film was like a tone poem, rather than a straightforward, linear trudge through his ideas.”

If Fisher warned that “Those who can't remember the past are condemned to have it resold to them forever”, Mellor and Poulter respond: “The film is not nostalgia. Fisher warned against that. It is an evocation of failed promised futures. And in doing so, it becomes a kind of working group for collective dreaming – a counter to the doom scroll machine of capitalist realism.” And again: “Refusing the misery feed and returning to action. Turning toward each other, asking new (old) questions.” Not a film about Fisher, then, but the symptom of a collective need to return to him.

To understand why Fisher keeps returning, we must understand where he came from. It all began in 1995, when Fisher took part in an experiment aimed at pushing the nascent technoutopian culture toward more ambiguous and disturbing extremes: the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU) at the University of Warwick. It was an anti-academic and controversial research lab in which continental philosophy, rave culture, science fiction, chaos theory and esotericism coexisted in a dystopian and nihilistic mix. When, as early as 2003, the experiment was rejected by the university, Fisher launched the blog K-Punk, destined to become a central node of online cultural criticism. It was here that his excitement for the future — the idea that what is not yet could erupt into the present and transform it, what the CCRU called hyperstition — converged with a growing awareness of its progressive disappearance, replaced by a present endlessly repeating itself. This is where his most recognisable style and lexicon took shape: hauntology, a term borrowed from Derrida to describe an imaginary haunted by the ghosts of past styles and foreclosed possibilities; and capitalist realism, the observation that “Capitalism seamlessly occupies the horizons of the thinkable”, along with its physical and psychological repercussions on the individual.

It has often been said that Fisher’s appeal lay in his ability to weave popular culture and everyday life together with philosophical concepts and political theory. And it is true: from Christopher Nolan’s films to Star Wars, from Nirvana to Drake — yes, that Drake, quoted at the opening of Ghosts of My Life (“Sometimes I feel like Guy Pearce in Memento”) — Fisher made thought immediately accessible. If pop is the meeting point between capitalist product and collective perception, Fisher understood and articulated it better than anyone. As Gavin Butt, who co-curated Post-Punk Then and Now with him, told me, Fisher “he was a model of what a popular intellectual could, and still can, be. He was a brilliant, fluid writer who was able to defamiliarise the broad smorgasbord of attention and distraction in late capitalist culture”.

There is also a strange kind of disembodiment that has happened with Mark’s work, which happens to many authors and artists after they die.

Macon Holt

Yet the deeper one goes into his thinking, the clearer it becomes how restrictive the role of cultural critic was for him. Every pop reference, every ready-to-hand citation, conceals Fisher’s elusiveness — that vertiginous abyss shared by so many but perhaps impossible to define before him. “The allure that the weird and the eerie possess is not captured by the idea that we ‘enjoy what scares us’. It has, rather, to do with a fascination for the outside, for that which lies beyond standard perception, cognition and experience.” This is where his magnetism lies: ever closer to our present, ever more relatable, yet at the same time irreducible and elusive, up to the tragic ending that seems definitively to deny comprehension.

Fisher is often remembered for his struggle with depression, culminating in suicide. It is an inescapable fact, but a reductive one. As Mattie Colquhoun told me, his figure recalls that of Walter Benjamin: “an indispensable critic of our world who has nonetheless come to represent one of its great tragedies”. Simon Reynolds confirms that “Mark had a capacity to see things clearly, which inevitably means recognizing the darkness at work in the world, all the soul-destroying forces. Seeing things clearly can bring anyone to despair.” But — and here lies the vital tension that still makes his thought resonate — “On the other hand, Mark was capable of great enthusiasm about things – usually happening in popular culture or its fringes – that he found inspiring and that he felt contained some kind of utopian potential or anti-hegemonic (to echo Gramsci again) power.He would get incredibly excited by some very mainstream works like The Hunger Games movies. Or Lily Allen’s #1 UK hit ‘The Fear’. Anything that was saying ‘this way we are living is insane and unjust and it’s making us miserable, there must be a better way’.” If, on the one hand, Reynolds continues, “Mark was a great believer, and defender, of the idea of critique – the importance and necessity of negativity”, on the other this stance was grounded precisely in a radical faith in the possibility of change.

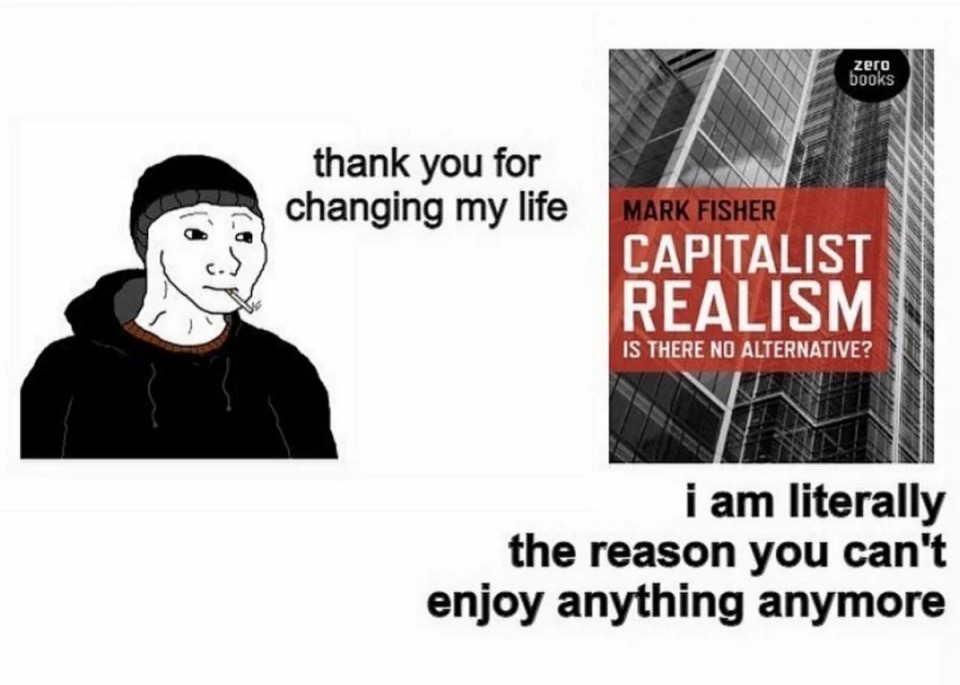

Thus his philosophy continues to resonate, not so much for its now-canonised concepts or pop references, but as an invitation to resist the present, to believe in an alternative, and to reactivate the potential of unease in a time when it is everywhere yet paralysed. This is why reading today a ruthless and bitter book like Capitalist Realism can be “providing a reason to hope, when I for one was just about ready to despair”, as Alex Niven wrote in a letter to Fisher he never had the courage to send but published upon news of his death: “it felt like coming up for air after a long time spent underwater.”

The film is not nostalgia. Fisher warned against that. It is an evocation of failed promised futures.

Sophie Mellor & Simon Poulter

It is significant that, after his death, his students painted one of his phrases on the Goldsmiths library — the university where he taught — as a gesture of collective tribute, and even more significant is the vital force of the phrase itself: “emancipatory politics must always destroy the appearance of a ‘natural order’, must reveal what is presented as necessary and inevitable to be a mere contingency, just as it must make what was previously deemed to be impossible seem attainable”.

“There is also a strange kind of disembodiment that has happened with Mark’s work, which happens to many authors and artists after they die,” Macon Holt tells me. “For anyone who came into contact with his work after 2017, there is always going to a little bit of myth about Mark, which can be a powerful way to engage with a thinker but also a dangerous one. […] In short, I would say that nine years on from his passing, his work makes more sense to more people than ever before, but at the same time the more sense an analysis like capitalist realism or hauntology or the call for acid communism makes, the more important it is to try and let the myth go so we can keep thinking with through and beyond Mark’s work.” Not to commemorate him, but to use him. Because, Holt concludes, “the point of the writing is to help us change the world together and not just examine it.”

In this sense, Fisher is neither a relic nor a pop icon. He is an active spectre. His ideas haunt us not because they belong to the past, but because the world he diagnosed has become our own. To keep reading him today is not nostalgia: it is an exercise in reactivation. Paradoxically, it is hope.