In the 1980s and ’90s, buying a packet of merendine — Italy’s ubiquitous individually wrapped snack cakes — was never just about food. It was part of a layered ritual: the hand rummaging through the package in search of something hidden, the rustle of plastic wrapping a small mysterious object, the discovery of an unexpected shape. The sorpresina, the little surprise, was not an accessory to the product but an integral part of it, often the primary reason for the purchase.

Italian food companies, from Mulino Bianco — the country’s most iconic producer of breakfast biscuits and snack cakes, synonymous with domestic childhood rituals — to Ferrero, a world-renowned confectionery group headquartered in Italy, understood early on that the perceived value of a product could be multiplied by the inclusion of a physical object. This was not merely a marketing tactic but the construction of a parallel universe, made of collections to be completed, figurines to be traded, miniatures to be accumulated. The sorpresina transformed the solitary act of consumption into a social one: it generated conversations in school courtyards, negotiations between classmates, temporary alliances formed to obtain the missing piece. For younger millennials, snack cakes sat at the base of the consumer desire food chain — cheap, accessible, and woven into everyday life.

The anatomy of desire

What makes this mechanism so powerful? The answer lies in a carefully calibrated combination of psychological elements. First, randomness: you never know what you’re going to get. Neuroscience studies show that uncertainty around reward triggers a stronger release of dopamine than predictable outcomes. Research published in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience suggests that dopaminergic response peaks when the probability of obtaining a reward sits at around 50 percent — a condition of maximum uncertainty. It is the same mechanism that fuels gambling. Then there is seriality: surprises belong to numbered collections, with common pieces and rare ones, creating a hierarchy of value that continuously feeds desire. Finally, tangibility: these are real objects, occupying physical space, meant to be touched, displayed, exchanged. This mechanism is not limited to children. Parents were often accomplices, themselves nostalgic for similar surprises from their own childhoods.

The great disappearance

Then, gradually, the surprises began to vanish. There was no single date, no official announcement. Today, packages of snack cakes, breakfast cereals and chips contain only food. The reasons are multiple: stricter food safety regulations, particularly around choking hazards; rising production costs; and environmental concerns. Millions of small plastic objects destined to be forgotten at the bottom of drawers are difficult to justify in an era increasingly attentive to sustainability. Companies have opted to replace physical surprises with alternative systems — loyalty schemes, prize draws, digital promotions.

That desire has survived, but it has lost a crucial quality: the illusion of gratuity: mystery is no longer incidental, but explicitly engineered, priced, and sold.

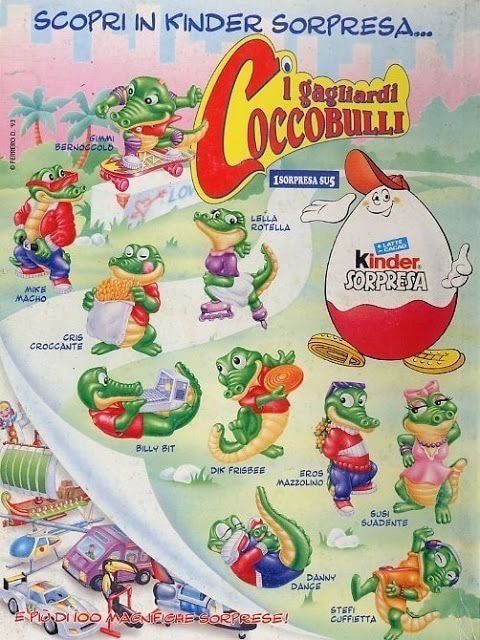

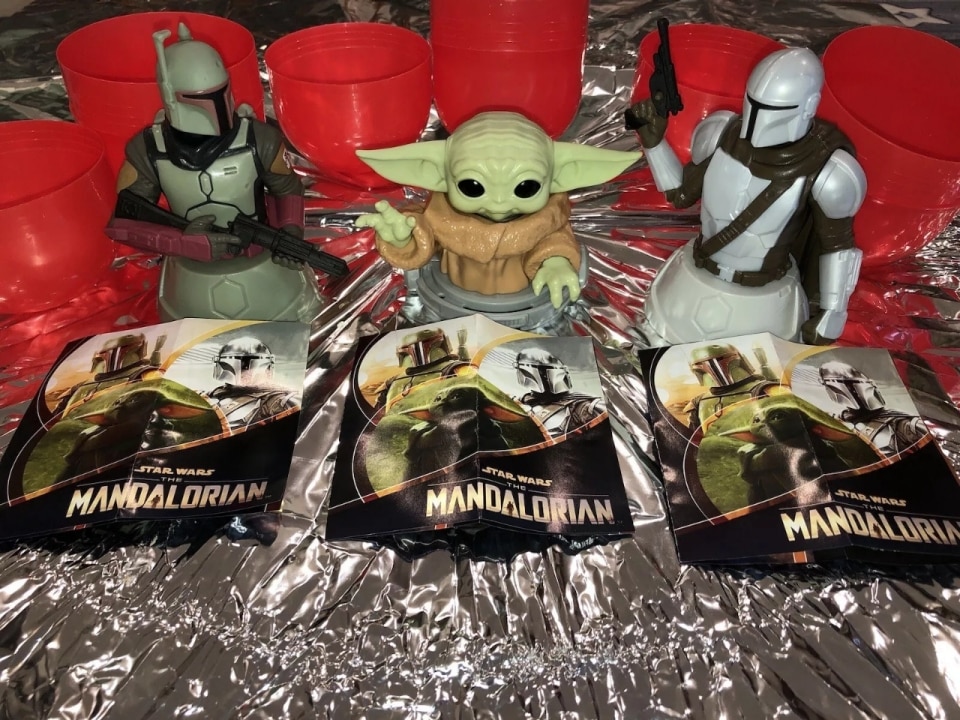

Kinder Surprise stands as an exception. Ferrero has preserved the original structure: a chocolate egg containing a capsule with a toy inside. Yet even Kinder Surprise has evolved. The toys are no longer what they were thirty years ago: safer, with fewer small parts, often accompanied by QR codes to scan on a smartphone, dedicated apps, or augmented-reality experiences. The physical surprise becomes a bridge to a virtual universe. The small plastic figurine is no longer an end in itself but a key that unlocks digital content, mini-games, animations.

The new collectorship

In the meantime, the desire to collect has shifted elsewhere. In the world of video games, skins, badges, avatars and cosmetic items replicate the same psychological mechanisms once embedded in physical surprises: rarity, exclusivity, social status. A rare skin in Fortnite or CS2 signals dedication, skill, and belonging to a community. The market for CS:GO skins alone is valued at over one billion dollars. These digital objects function much like the figurines of the past: they are accumulated, displayed, and used to construct identity. Yet they lack something essential — tangibility, weight, the possibility of being passed hand to hand in a school courtyard.

The Labubu phenomenon and Pop Mart’s blind boxes show that physical surprise has not disappeared; it has simply relocated. These figurines, sold in sealed boxes with no indication of which character lies inside, reproduce exactly the logic of the old sorpresine: randomness, collection, exchange, the hunt for the rare piece.

But there is a crucial difference compared to snack cakes. Blind boxes are standalone products, sold explicitly as such. The classic sorpresina, by contrast, was a bonus — an extra hidden within the price of the snack. Its cost was invisible.

The mechanisms of randomness and collection still work. Unboxing videos generate millions of views; online communities form around trading, speculation, and the hunt for rare items, much as they once did in school courtyards thirty years ago. But the surprise has exited the snack cake to become an autonomous commodity, resold at staggering prices. It is no longer the extra that accompanied everyday consumption; it is the product itself. That desire has survived, but it has lost a crucial quality: the illusion of gratuity. The feeling that a surprise could be hidden anywhere — even inside the wrapper of an industrial brioche — has given way to a fully monetised system in which mystery is no longer incidental, but explicitly engineered, priced, and sold.