After a few rather dull years, in which the world of cameras adapted to the shockwave generated by smartphones, things have recently become more interesting again. It seemed that no one wanted a camera anymore, except professionals. Then, all of a sudden, Fujifilm launches a bizarre yet extremely fun digital half-frame camera, Kodak’s mini-camera sells out for Christmas, a startup introduces a strange AI camera, and on Vinted and similar platforms the digicam craze shows no sign of slowing down. Meanwhile, Sony updates its prestigious fixed-lens 35mm camera, the RX1R, while after a decade Ricoh has finally renewed the GR, a very special compact camera with a vast community that has only continued to grow over time.

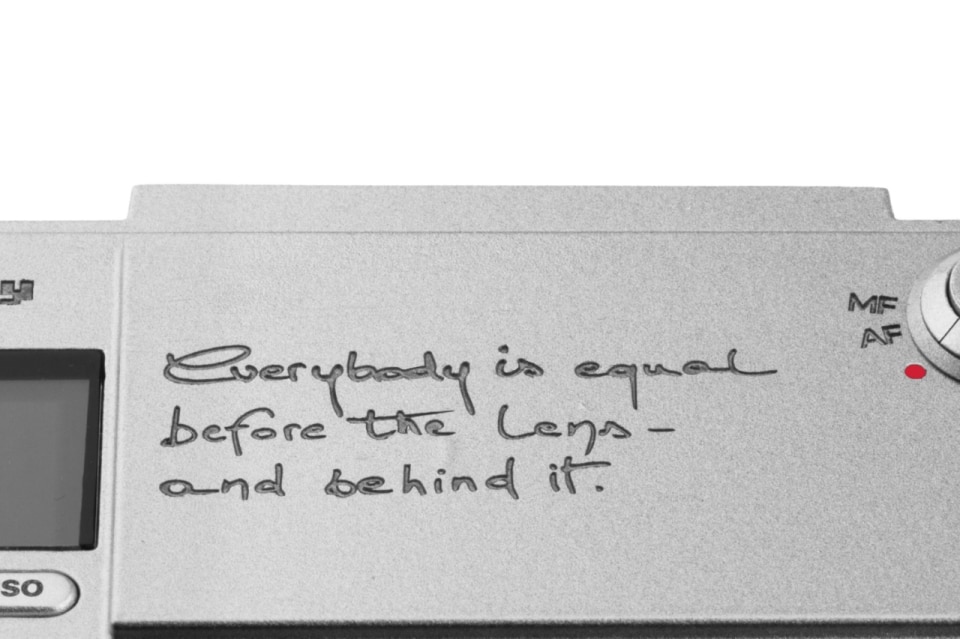

Alongside digital, film cameras are also resurfacing. It is almost as if the ease with which images are produced today—even artificial ones, with Midjourney and other AI tools—has paradoxically renewed attention toward imperfection, unusual formats, and surprise. Thus, alongside timeless disposable cameras and entry-level models such as the Kodak M38 or the Agfa Vista, new analog cameras with significant price tags are also arriving. Leica paved the way by relaunching the M6 in 2022, followed two years later by the Rollei 35AF, a completely new film camera launched at over 800 euros.

In this context, we have selected three unconventional cameras capable of delivering surprising results. Designed as adventure companions for winter and beyond, they are perfect for exploring cities and landscapes and for shooting in a way that differs from the usual. One note: these are not always immediate tools and may discourage beginners; however, all of them can also be used in automatic mode, including the two analog cameras in this trio.

Lomo MC-A

Between the late 1990s and the early 2000s, digital photography became mainstream, progressively replacing film. In reaction, many enthusiasts continued to shoot analog, often choosing fun, immediate, and unreliable cameras capable of producing images that were sometimes awful, sometimes beautiful, but always surprising. This is how toy cameras such as the Holga or the Diana were born, as well as the Lomo LC-A, a Soviet compact camera from the 1980s rediscovered by a group of Viennese students and which became the starting point of lomography.

View gallery

View gallery

Let’s say it straight away: the MC-A is a successful camera. It combines analog photography with digital support, making accessible—without the need for DIY modifications—many of the practices that built the lomographic aesthetic: multiple exposures, split shots using a dedicated filter, flash with colored filters. Added to this are more advanced tools, such as aperture priority, manual shutter speed control, exposure compensation up to three stops, the ability to manually set ISO, and zone focusing. Lomography also got the body design right: even if it doesn’t immediately look like it in images, the MC-A is effectively a restyling of the old LC-A, and when the two cameras are placed side by side, their kinship is evident. Moreover, the organization of buttons and dials is genuinely well designed.

View gallery

View gallery

Lomography’s camera delivers the magic of analog without falling into a forced lo-fi aesthetic. On the contrary, the MC-A especially enhances more sensitive color films when used in good lighting conditions. At the same time, it integrates contemporary solutions, from USB-C battery charging to an extremely flexible control system. It can be a complex or intuitive tool, used manually or left to automation. Every combination leads to a different result, and this is precisely where its appeal lies. The only downside is that film and development no longer cost what they did twenty years ago.

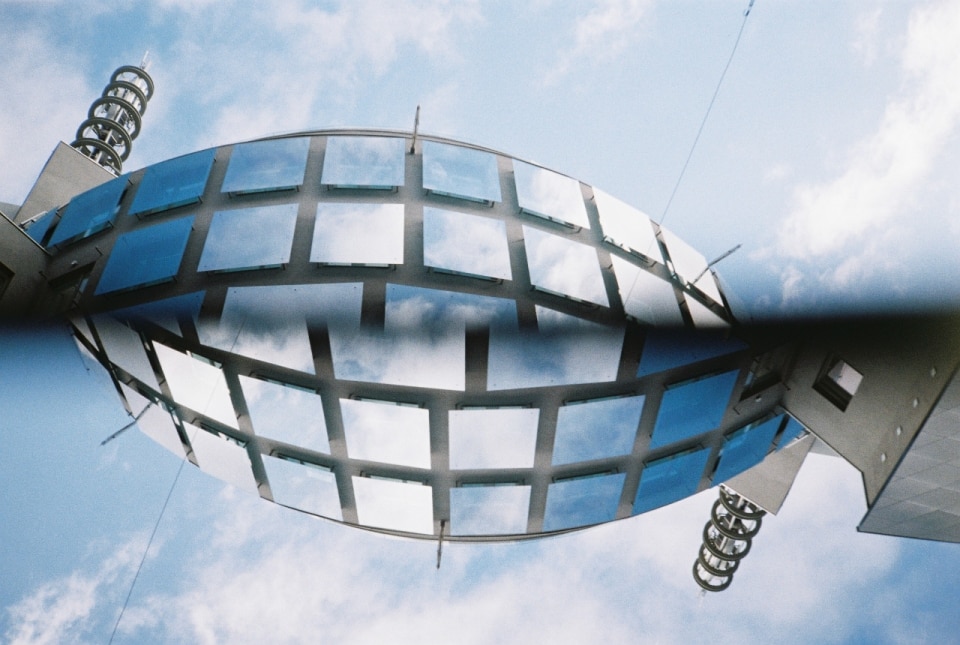

Insta360 Ace Pro 2 with Xplorer Pro

Released months ago, the action cam with Leica lenses continues to surprise. This is also because Insta360 has realized it has a potentially hybrid device on its hands, halfway between a video camera and an experimental photographic tool. After the metal grip co-created with Tilta—one of the most interesting objects seen in recent years in the tech field—the brand pushes further in this direction with the Xplorer Pro, an even more photographic grip, accompanied by the launch of a portable printer.

The grip improves battery life and introduces physical controls: a shutter button, a zoom lever (within the 1x–2x range allowed by the lens), and a configurable dial for exposure, modes, or filters. Everything is designed to increase control, both in video and in still photography, with the idea of producing images to be shared or printed immediately.

View gallery

View gallery

It should be made clear: this is not a camera that also shoots video, but an action cam that can be used in a lateral and experimental way to obtain images outside the ordinary. The additional lenses—cinematic or macro, sold separately—help move away from the typical action-cam aesthetic, fascinating but often difficult to manage. In urban, travel, or exploration contexts, it can become a curious and surprising tool. It is a shame, however, that there is still no official teleconverter: a rendering closer to a 35mm or 50mm focal length would make it even more versatile.

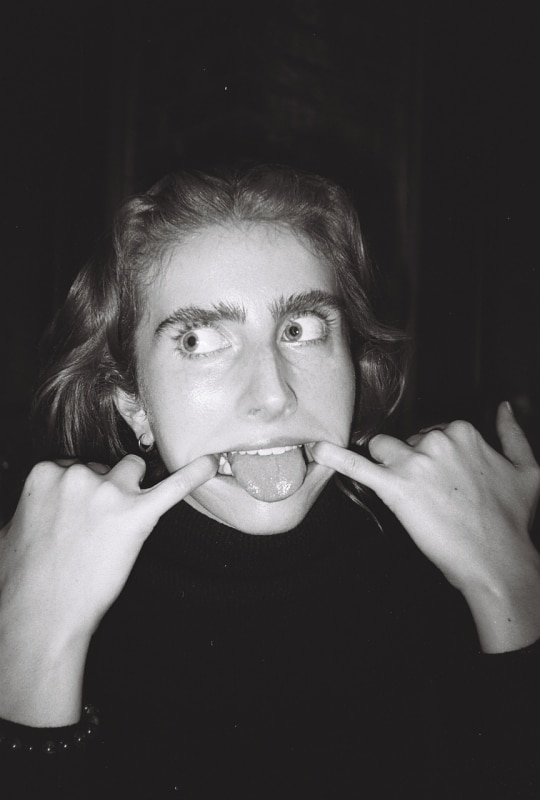

Pentax 17

What is appealing about a camera that costs more than 500 euros, shoots half-frame film in vertical orientation, and—despite its magnesium top plate—delivers a slightly plastic feel?In reality, quite a lot. Starting with the body, which is a continuous citation of Pentax’s history, a brand now owned by Ricoh and which had not launched a new camera in years. Designer Takeo Suzuki references the Pentax Auto 110 in the film advance lever, DA lenses in the grip texture, the logo from the legendary Pentax 67, and the rewind arrow from the Spotmatic SP. It is an accurate work of citation, also recounted by The New York Times in an enthusiastic review.

But the Pentax 17 does not live on nostalgia alone. Its operating scheme is original and almost disorienting. A dial allows the selection of different modes, something unusual for an analog compact camera. These are not classic manual controls, but rather a series of semi-automatisms that allow users to “play” with shutter speeds and apertures without having full control. There are modes designed for natural light and others that integrate flash use.

Particularly fascinating is the “bokeh” mode, a term that refers to portraits with blurred backgrounds, an effect that smartphones now simulate via software. On a half-frame camera it might seem contradictory, yet the results are surprisingly convincing, especially considering the format and the camera’s design intent.

Another decidedly analog detail: the 25mm lens (equivalent to about 38mm in full frame) has no autofocus. It uses zone focusing with numerous options directly on the lens. The risk of imprecise results is real, especially without knowing the exact aperture value. But this, too, is part of the game. The learning curve is steep, and those without much experience may find it fascinating yet enigmatic. On the other hand, it is hard to imagine choosing it for convenience.