The first truly unforgettable object in Wes Anderson’s filmography is the submarine from The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. While his earlier films had already featured objects that could only exist in his distinctive universe – like suitcases, books, desks, and (of course) portable record players – this submarine introduced the first truly impossible object. It defies all logic, existing solely in a fantasy world. For the first time, Anderson transported his symmetrical, meticulously crafted world into the realm of pure fantasy. The story, which follows an oceanographer, his son, and their eccentric team of collaborators, is filled with imaginary creatures observed from vessels that challenge the very laws of physics. It marked Anderson’s first dive into animation.

From there, he ventured into fully animated films, and then back into live-action, adding increasing levels of surrealism with every new project. In each film, more objects began to populate his world. Even in Moonrise Kingdom, shots focused on the protagonists’ books and belongings, elevating them to co-stars in the story. These objects – shown one after another – conveyed as much about the characters’ world as their clothes and the décor around them. But at that point, these were still real – or at least believable. Then something shifted. Starting with The Grand Budapest Hotel, Anderson’s animation experience began to seep into his live-action work as well. The actors moved like animated characters: entering scenes, crossing shots in quirky ways (a head might suddenly pop out from behind a door). Makeup, hairstyles, and costumes went beyond eccentric and felt straight out of a cartoon. And with that, objects started becoming impossible – specifically designed, if you will.

The Phoenician Scheme, which recently premiered at Cannes, takes another step in this ongoing evolution of recreating reality in the film studio, a method Anderson has honed since Moonrise Kingdom. Since The Darjeeling Limited, Anderson has made it his mission to shoot in some of the world’s most iconic film studios. He’d already done this at Cinecittà to construct the massive submarine for The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, and since then, he’s steadily increased the amount of indoor filming, even for scenes meant to look like they’re outdoors.

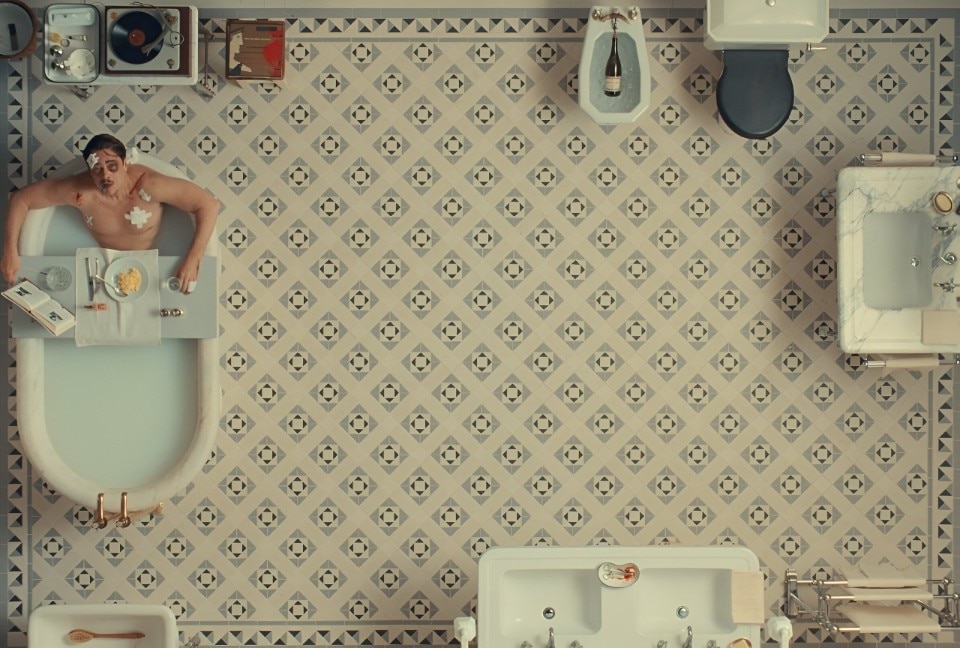

Now, even vast landscapes in his films are depicted as miniatures, like dioramas – such as in Isle of Dogs, which, despite featuring real people, is entirely animated. The Phoenician Scheme features wheat fields, forests, tunnels, and deserts that don't exist in the real world, all painstakingly built in a studio, with no attempt to make them look “real.” This is because, in the studio, nothing exists before filming begins – not even light. Every single element that will end up on screen is carefully selected. There are no “found” objects or location-based props here.

This method gives Anderson the freedom to fill his shots with objects that range from authentic relics to newly created items made to appear period-appropriate. Furniture and books often take center stage, sometimes even fantastical designs make an appearance. The Phoenician Scheme, for example, includes a portable lie detector, a 1940s airplane phone (with a handset designed to plug into the wall of an airplane), and a mind-boggling hand pump for blood transfusions – powered manually, in the absence of electricity. Anderson’s ability to build this world of intricate, unique objects has been evolving with every film. His four short films based on Roald Dahl’s stories for Netflix marked a key turning point, where he began exploring the world of illustration through his signature style.

And, of course, all of this is entirely consistent with the world Anderson has created – a universe that exists mainly because of its visual identity. It’s a world where electric machines have boxy shapes, worn appearances, and designs that belong to the Industrial Revolution rather than the age of consumerism. It’s a world where bombs look like something from Looney Tunes, with rubber-band-wrapped fuses and alarm clocks as timers. Hand grenades are all painted to resemble a set of suitcases. These details are easy to overlook because Anderson’s frames are so densely packed with elements, more complex and visually cohesive than ever. The Phoenician Scheme ends in a grand finale set in a kitschy, outlandish Egyptian-style palace, a scene both delightful and absurd. It’s easy to miss the sheer absurdity of objects designed in ways that would be insane in any other context. Anderson’s animated-style design is crafted to amuse, to bring a smile.

This approach to set design and props is radically different from how cinema typically handles these elements. While the usual goal is to lend credibility to the story by grounding it in the real world (or another world, like in fantasy or sci-fi), or to transport us into dreamlike states (as in musicals), in Anderson’s films, these objects do the exact opposite. Rather than grounding us, they pull us out of reality. Just when we start to think the story might be somewhat realistic, the set, costumes, hair, and furniture remind us: we’re not in our world. We’re in a place where anything can happen – where the laws of physics don’t apply, and quicksand could be as much fun as a swimming pool.

It’s a subversive artistic choice with a meaning that reaches far beyond any plot Anderson’s films might tell. It’s no accident that, in recent years, this design element – once seen as a strong part of his work – has grown to monumental proportions. With each new film, the intricate stage designs become even grander, while the writing’s tension and quality have waned. Characters are increasingly introduced, each with a distinctive look, and there’s palpable pleasure in constantly creating “models” worn by extraordinary actors. But very few of these characters have any real psychological depth. They’re mostly there to fill out the frame and wear the costumes.

@fandango Oh dear. Tickets for Wes Anderson's #ThePhoenicianScheme are on sale NOW! Waltzing into theaters May 30. #wesanderson #movietok #movie ♬ original sound - Fandango

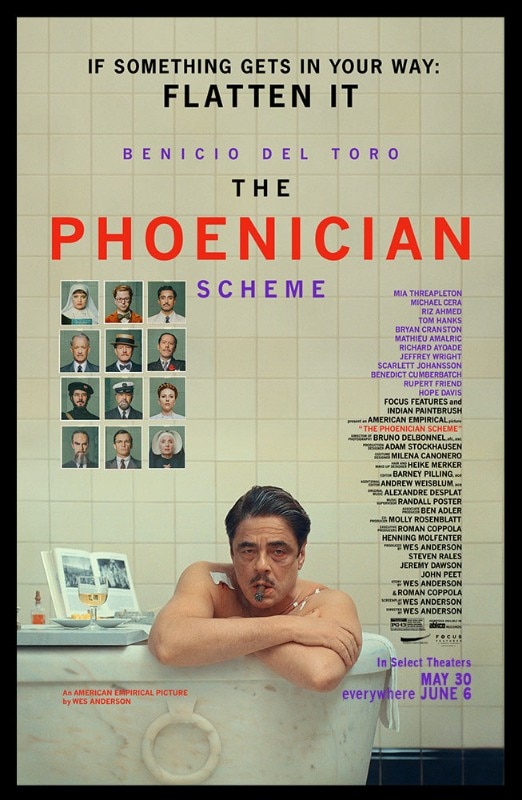

The Phoenician Scheme is no exception. The story follows a father who’s trying to convince his daughter to follow in his footsteps by involving her in a grand adventure around the world. To convince several business partners to join an ambitious project, he must visit them one by one. Each new location is introduced by a postcard drawing, showing an iconic building from the place in meticulous detail. The locations feel like they could’ve been plucked from nineteenth-century miniatures. Each one has its own unique look and color palette, resembling a new page in an illustrated book, each with its own visual universe.

In this film, a character – who, like everyone else, has a strict persona – can shed it. This doesn’t typically happen in Anderson’s work, because his characters, like those in cartoons, tend to have an immutable look (the first to sport this feature were the Tenenbaums, when Anderson still felt the need to justify it within the plot). But here, we have a shy, meek little professor who, we soon discover, is a spy quietly observing the protagonists. Once his true identity is revealed, he shows everyone he’s someone else entirely by changing his appearance. This is a shift from one character design to another. It’s only when he changes his hairstyle, mustache, and the way he wears his jacket, that he appears different – not only to us, but also to the other characters. It’s not the revelation itself that solidifies his identity, but the fact that the character can adopt a completely different look. That’s enough; it’s another cartoon, another persona. It’s almost like a visual representation of Anderson’s creative process in how he designs his actors.

This little professor has boxes for his insect collection, a net for catching them, and various other tools that define him. But when he transforms, he loses them all – he was only using them to create the illusion that he was someone else (and it worked!). In Anderson’s world of designed, impossible objects, their purpose isn’t merely to serve function; they help define the character. Houses, with their amazing interiors, are the primary objects of definition. These are Anderson's favorites, the ones he pours the most care into. The stark grayness of the protagonist, played by Benicio del Toro, is embodied in a drab, ash-colored dining room with no furniture, where he shares meals with his many children. This room is meant to evoke affection, but it’s as barren as he is. In contrast, the luxurious airplane he travels in for work is neat, professional, and packed with absurd technology and intriguing objects – because that’s what he truly loves. Just like Wes Anderson loves objects.

Opening image: Wes Anderson, La Trama Fenicia, 2025