by Ramona Ponzini

Cronenberg’s films take us into unstable territories, explorations of flesh, mind, and the spaces that contain them. His cinematic worlds are shaped by uncertain geographies, in which brutalist buildings become breeding grounds for contagion, machines turn into erotic extensions of the human body, cities twist into mazes of alienation, and skin becomes a boundary meant to be crossed. While horror is often linked to the irrational, Cronenberg approaches it with clinical precision: mutation, disease, and the fusion of human and machine aren’t aberrations – they're new forms of being.

His filmography can be read through five major aesthetic and conceptual landscapes. In the 1970s, films like Shivers, Rabid, and The Brood use brutalist horror to turn the body into an architectural virus – a biological threat that contaminates both the space and the individual. In the 1980s and 1990s, with Videodrome, Dead Ringers, Crash, and eXistenZ, Cronenberg redefines the relationship between flesh, technology, and desire, by creating a biomechanical aesthetic that fuses the organic with the artificial. In the 2000s, with A History of Violence and Eastern Promises, his focus shifts to cities and suburbs, examining violence as a form of social architecture.

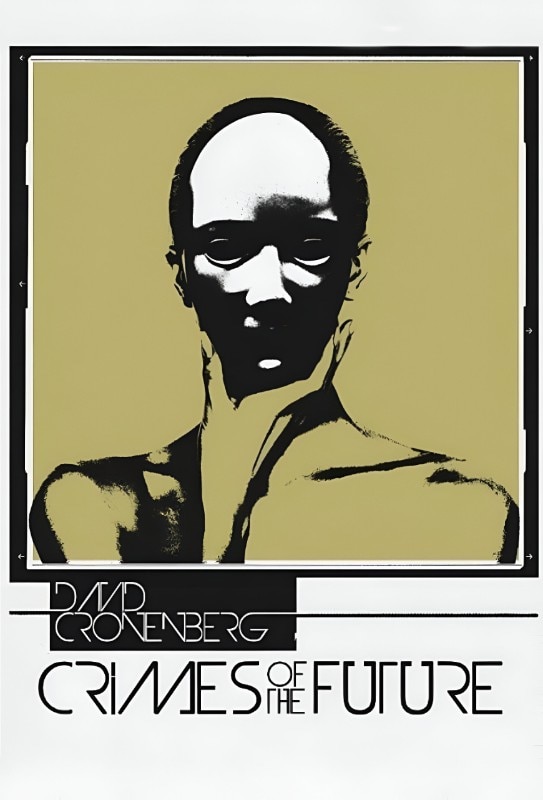

The following decade sees a split between two iconic metropolises: Cosmopolis and Maps to the Stars stage a symbolic duel between New York and Los Angeles, between hyper-controlled capitalism and the narcissistic hallucinations of the Hollywood machine. Finally, in Crimes of the Future (2022) and his latest work The Shrouds (2024), Cronenberg returns to the flesh, closing the loop with a biomechanical requiem on the transformation of art and body.

1. The body as architectural infection

Early Cronenberg emerged in the shadow of reinforced concrete, amid the ruthless geometries of brutalism and the sterile surfaces of a decaying future. Films like Shivers (1975), Rabid (1977), The Brood (1979), and the first Crimes of the Future (1970) embody a form of biological horror that is, above all, spatial. In these films, architecture isn’t just a backdrop, it becomes a living organism, a body into which disease, contagion, and genetic mutation seep in.

The false promise of modern rationality lurks deep within the brutalist landscapes of residential high-rises and futuristic medical centers, quickly corrupted by uncontrollable human urges. In Shivers, the Starliner Tower (a stand-in for Mies van der Rohe’s Hi-Rise No. 3 on Nun’s Island, Montreal) is a utopian enclave that soon turns into a lab of primal desire, overrun by parasites that reduce its residents to sexually ravenous hosts. In Rabid, infection spreads beyond the walls, overtaking the city like an unstoppable disease. In The Brood, the body itself becomes an incubator of violence, bringing this reasoning to the extreme.

In these films, Brutalist architecture functions not only as an aesthetic choice but also as a conceptual framework. The cold geometry of the spaces, their pretense of control and function, clashes with rebellious flesh. Cronenberg exposes the illusion of modern progress: far from being rational, it is organic, impulsive, and uncontrollable. This tension between order and entropy is already manifested in Crimes of the Future (1970), where an epidemic has wiped out the female population, leaving a world inhabited solely by men. Here, bodily distortion mirrors a distortion of the cinematic language, made of fragmented storytelling and claustrophobic settings.

This first phase of Cronenberg’s cinema lays the groundwork for all that follows. The body is a fragile architecture; the city, an infected organism; identity, a process of constant mutation. Brutalism – defined by its rigid lines and bare surfaces – becomes the outer shell that eventually cracks, revealing the horror of the flesh hidden beneath its geometry.

Cronenberg structures the film around an architectural tension. The small town is open and linear, filled with warm, inviting spaces. Violence is the foreign element that disrupts this harmony, exposing the American dream as a carefully maintained fiction.

2. Design, machines, and video games

In the 1980s and 1990s, Cronenberg shifted away from the imposing, rationalist architecture of his early work and embraced a fluid, hybrid aesthetic where design is always ambiguous: seductive yet grotesque, erotic yet monstrous. If his early horror stems from flesh in revolt, this new phase merges body with the device, transforming it into an interface, an extension, a simulacrum. Desire congeals into metal; video games graft themselves into flesh; the scalpel becomes the fetish. Technology is no longer a tool – it becomes flesh itself.

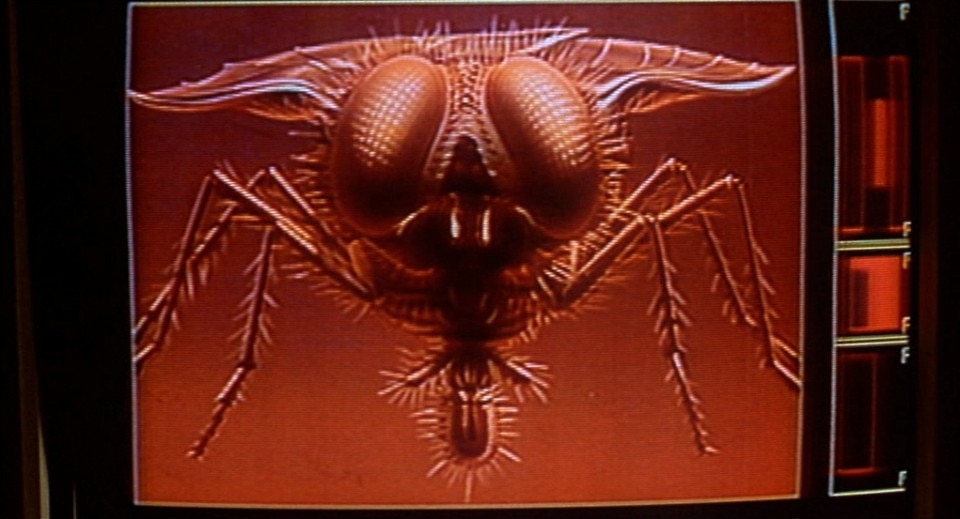

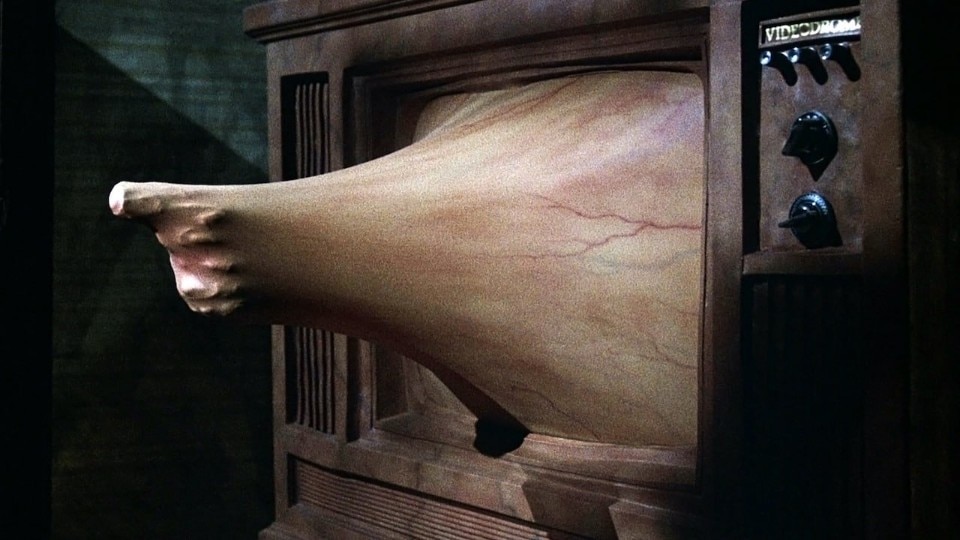

With Videodrome (1983), Cronenberg inaugurates the era of the mediated body, where technology is not external but a force of organic mutation. The main character Max Renn (James Woods), a TV executive obsessed with extreme content, stumbles upon a pirated broadcast that is more than mere entertainment – it’s a virus, capable of warping perception and reshaping the body. Videotapes are inserted into a fleshy slit in the stomach; screens fuse with skin; the body becomes a pliable medium. Every detail in Videodrome anticipates the discourse of virtual reality and human-tech hybridization that would dominate the decades to follow. The design of the film’s objects – pulsating TVs, biomechanical weapons, organic screens – creates an aesthetic where electronics are deformed, no longer rigid, an extension of the body.

If Videodrome explores the fusion of flesh and image, Dead Ringers (1988) delves into the entanglement of identity and object. The story of the Mantle twins (Jeremy Irons), gynecologists specializing in fertility, becomes an unsettling meditation on duality, loss of individuality, and the transformation of medical tools into perverse prosthetics. The Mantles’ custom-made instruments, with their alien forms, seem lifted straight from an H.R. Giger biomechanical nightmare – sleek, deadly, and designed not to heal but to mutate. Here, design is the outward manifestation of desire: a fusion of surgical precision and corporeal delirium.

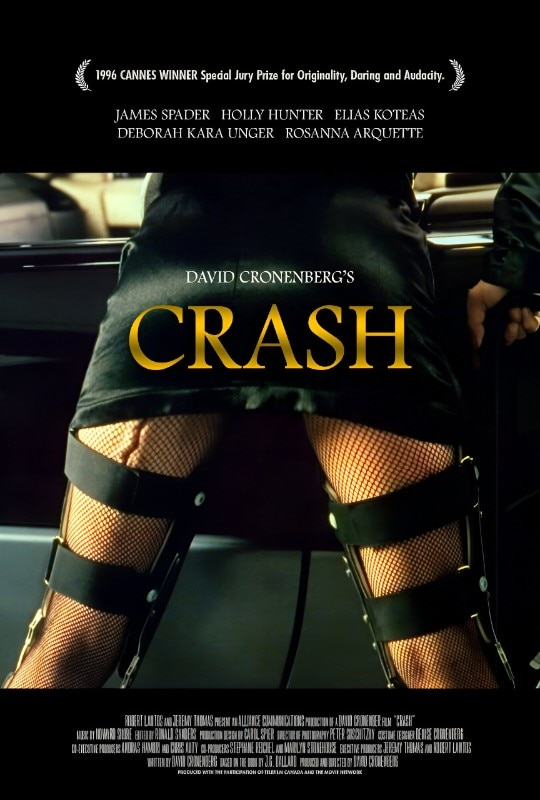

In Crash (1996), Cronenberg pushes the body-machine aesthetic to its limits. Based on J.G. Ballard’s novel, the film explores the eroticization of car crashes through the fusion of metal and flesh. Gutted cars, scars on the bodies, the details of seatbelts pressing against skin: everything in Crash turns the automobile into an extension of human desire, a fetish that amplifies sexuality until it becomes indiscernible from violence. Car design – with its gleaming curves and smooth surfaces – is laid over the human form, while scars emerge as a new form of aesthetic language.

Where Crash fuses flesh with metal, eXistenZ (1999) binds it to the virtual. The film is set in a world ruled by organic video games, in which reality is fluid and technology is alive. The game consoles in eXistenZ are not plastic objects made of circuits – they’re pulsing creatures, moist membranes connected to players through bio-ports implanted in the spine. The distinction between game and reality vanishes into a recursive loop of perception, reflecting the fear of total simulation, where the body is the support for the experience. The film’s design is key to its impact: consoles look like living things, controllers are soft outgrowths, buttons react like nerve tissue.

3. Violence as the architecture of power

In Cronenberg’s films of the 2000s, mutation is no longer physical – it becomes social. Identity is transformed the moment it comes into contact with violence, which contaminates the individual and rewrites their role in the world. The contrast between small-town life and the big city becomes a lens through which to examine the construction of the self and the fragile balance between normality and brutality. The former pretends to be immune to evil; the latter embeds it in systems of power. In both, violence operates as a universal language.

In A History of Violence (2005), the American suburb is portrayed as a fragile utopia – a bubble of serenity concealing an unresolved past. Tom Stall (Viggo Mortensen), the owner of a diner in a quiet Indiana town, appears to be the ideal family man. But his calm life unravels when he kills two armed robbers in self-defense. His heroic gesture catches the attention of the Philadelphia mob, who recognize him as Joey Cusack, a former hitman who vanished years earlier.

Cronenberg structures the film around an architectural tension. The small town is open and linear, filled with warm, inviting spaces, empty streets, and wide skies. Violence is the foreign element that disrupts this harmony, exposing the American dream as a carefully maintained fiction. When Tom returns to Philadelphia to confront his gangster brother (William Hurt), the city stands in stark contrast with the suburbs: shadowy, ruled by rigid geometry and the iron grip of organized crime. The journey back to his roots is a descent into hostile territory, a past that engulfs the main character and forces him into a confrontation with his true identity.

If A History of Violence explores the small town as an illusion of innocence, Eastern Promises (2007) brings the conversation fully into the city, turning it into a labyrinth of power and belonging. Set in a harsh, nocturnal London, the film follows Nikolai Luzhin (Viggo Mortensen), a driver for the Russian mafia, and Anna Khitrova (Naomi Watts), a midwife trying to protect the newborn daughter of a young prostitute who died of an overdose. In Eastern Promises, the city is a living organism – an environment where control is etched into stone and blood.

Unlike the deceptive calm of A History of Violence, Cronenberg’s London holds no illusions but ancient codes and immutable rules. Violence is ritualized, transmitted through symbols carved directly into flesh. The tattoos of the Vory v Zakone, the Russian criminal elite, are not mere decoration but a system of identification, hierarchies written on the body. Nikolai navigates this world with ambiguity, ultimately revealed to be an undercover agent. But his transformation isn’t a redemption arc: it’s a power shift, an initiation into a structure that outlasts the individuals within it.

The body is a fragile architecture; the city, an infected organism; identity, a process of constant mutation. Brutalism – defined by its rigid lines and bare surfaces – becomes the outer shell that eventually cracks, revealing the horror of the flesh hidden beneath its geometry.

4. New York and Los Angeles: the twilight of power

In the 2010s, Cronenberg turns his gaze to two symbolic capitals of the contemporary West: New York and Los Angeles. Cosmopolis (2012) and Maps to the Stars (2014) explore the dissolution of power in its most abstract forms: capital and myth. While earlier films examined threats that were biological, technological, or social, here the danger is the collapse of reality itself, consumed by hypercontrol that spirals into chaos.

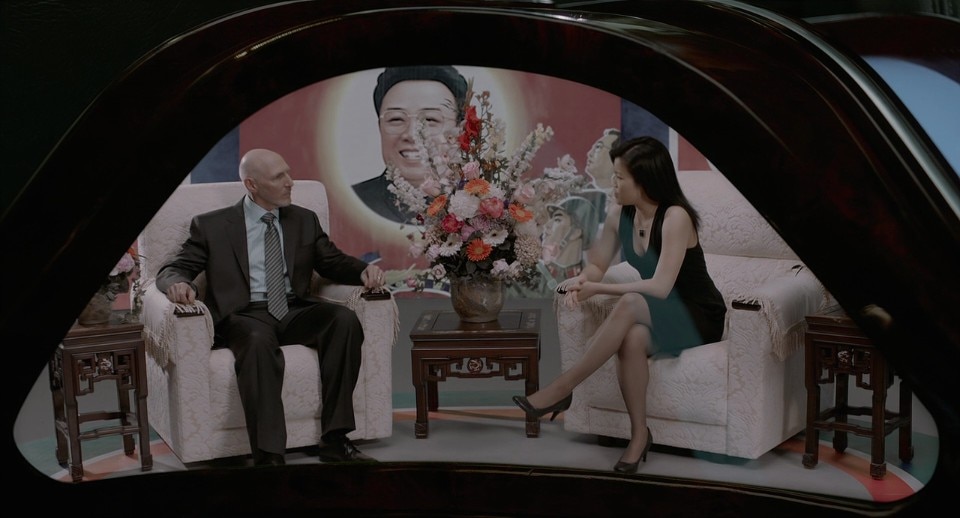

With Cosmopolis, Cronenberg adapts Don DeLillo’s novel of the same name, transforming a stretch limousine into a sealed capsule of isolation and self-destruction. The protagonist, Eric Packer (Robert Pattinson), is a young finance billionaire who spends the entire film crossing Manhattan in his limo as his empire crumbles under the weight of market speculation. In this static journey, the city becomes a mirror of Eric’s psychological disintegration: an unreal, sterile landscape inhabited by cryptic figures who embody the ghosts of financial power.

The film’s aesthetic is defined by the sterility of luxury and the rigid geometry of its settings: the icy interiors of the limo, the glass barrier separating Eric from the chaos outside, the stage-like structure of the dialogue. Here, New York is no longer a vibrant metropolis but a wasteland of data and transactions, a spectral architecture where the protagonist drifts without ever truly touching the world. Capitalism is depicted as an entropic force: the logic of absolute control inevitably leads to collapse. For Eric, the only genuine experience left is violence – annihilation as the last form of freedom.

While Cosmopolis dissects the decline of capitalism through the sterile lens of finance, Maps to the Stars offers a similarly bleak portrait of Hollywood and its toxic mythology. Los Angeles is more than a city – it’s a closed ecosystem, a self-referential loop of neuroses and obsessions where power is tied to fame and its endless replication. The film follows Agatha (Mia Wasikowska), a young woman returning to L.A. to reunite with her family – a dynasty of actors and producers consumed by incest and pathological narcissism.

The architecture of the city reflects the sickness at the core of its system: secluded hillside mansions, cold and impersonal interiors, swimming pools lit by artificial light – everything contributes to an atmosphere that is both opulent and haunted. In Maps to the Stars, Los Angeles is a ghost stage where the past never dies, and trauma passes from generation to generation like a hereditary curse. The city becomes an inferno without redemption, where obsession with image and success manifests in hallucinations, symbolic incest, and repressed violence.

5. The return to the body in recent years

In the 2020s, David Cronenberg returns with two films that reaffirm his lifelong obsession with the body and its transformations: Crimes of the Future (2022) and The Shrouds (2024). These works represent a mature and profound reflection on the themes that have defined his career, while also exploring new frontiers in the perception of flesh, whether evolving or decaying.

In Crimes of the Future, Cronenberg immerses us in an indeterminate future where humanity has adapted to a synthetic environment, triggering mutations and bodily transformations. The main character, Saul Tenser (Viggo Mortensen), is a performance artist who, together with his partner Caprice (Léa Seydoux), stages live surgical removal of new organs that his body spontaneously develops. These public performances blur the lines between art, pain, and pleasure.

The film revisits familiar Cronenbergian territory – like technology fusing with the human body – but takes it to a deeper level of introspection. Here, bodily mutations are not portrayed as aberrations but as the next step in human evolution. The setting is decayed and post-apocalyptic, populated by semi-organic technologies that echo the aesthetic of Cronenberg’s earlier work. The deliberately unsettling special effects emphasize the tangible nature of transformation, pulling the viewer into a deeply sensory experience.

In his most recent film, The Shrouds – which premiered and competed at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival – Cronenberg turns his focus to the theme of grief. Set in the near future in Toronto, the story centers on Karsh (Vincent Cassel), a tech entrepreneur who invents a cemetery system where graves are equipped with high-tech shrouds that livestream the decomposition of the bodies. This technology allows the living to observe the dead through an app, transforming mourning into a perpetual act of voyeurism.

The design of the film’s spaces reflects this fusion of intimacy and surveillance: minimalist, cold, and clinical environments that evoke a sense of detachment and control. The graves become screens, and the cemetery is transformed into a continuous exhibition space, where death is no longer hidden but watched and recorded.

Cronenberg has said that in The Shrouds, the shroud does not serve to conceal the body – it serves to reveal it. This inversion of purpose is echoed in the film’s set design, where every architectural element is conceived to expose, to display, to make visible what is typically kept out of sight.

In both films, Cronenberg intensifies his exploration of the flesh, redefining it as the ultimate frontier of human experience. He offers a provocative vision of the future in which the body and technology evolve in unpredictable ways. These works reaffirm Cronenberg’s ability to question the transformations of identity and perception in a constantly shifting world, all while maintaining the thematic coherence that runs through his entire body of work.

Opening image: David Cronenberg, The Shrouds, 2024