In Bong Joon-ho’s films, the design and architecture of spaces, as well as the way environments are structured, always double the meaning of the story. Not only do they foreshadow what will happen to the characters, but they also reaffirm their status. They function as a constant visual cue, ensuring that, as we watch the story unfold, there is no need to explicitly restate the characters’ circumstances—environments themselves do that for us.

In his films set in the present, this is often achieved by constructing spaces from scratch, as with the house in Parasite, built precisely to fit the needs of the narrative. In his science fiction films, however, it is imagined that society itself is responsible for designing its buildings and rooms in a way that enforces inequality. This was evident in Snowpiercer (2013), where the poor were confined to the last car of the train carrying all of humanity, far removed from the wealthy passengers at the front. The same principle applies in Mickey 17, his latest film.

The story follows a fool of the future who, in an attempt to get rich quickly, takes a loan from a lender known for torturing and killing those who fail to pay on time. Mickey is on the verge of defaulting. Desperate to escape, he joins a colony preparing to board a spaceship to colonize another planet. In a remarkable cinematic architectural gesture, the recruitment process takes place on the ground floor, at the center of a structure with a massive spiral staircase teeming with people—as if Mickey is already trapped by society before even embarking, just by signing a contract.

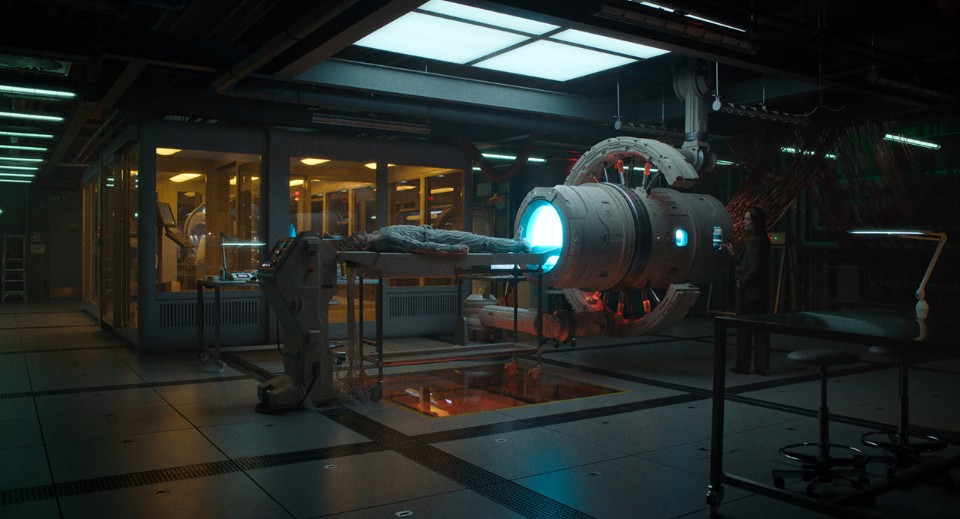

Being foolish, he signs without reading the fine print: he agrees to be “expendable” without understanding what it entails. Only aboard the ship does he realize he is part of an experiment. His body and mind are mapped so that he can be replicated endlessly. He is used as a test subject, sent to die in explorations, fed chemical agents, infected with diseases, and later cured with experimental vaccines. Not only is he killed without hesitation, but his corpses are discarded through a hole in the floor leading directly to a furnace, like waste.

No character needs to explicitly state that there is no respect for his life—the mere design of the disposal system equates him to excrement. Mickey dies 16 times before the film even begins; his seventeenth version, now on the destination planet, appears to die again during an exploration—only to unexpectedly survive without anyone knowing. When he returns to the spaceship, he discovers they have already created a Mickey 18. Now, two Mickeys exist simultaneously, which is strictly forbidden.

In the first scene, we see a version of Mickey emerging from the machine that “prints” him—this is the term used for the process. The sound design features a faint noise reminiscent of inkjet printers, and his body moves in fits and starts, advancing and retracting slightly, like a sheet of paper being printed. It is a striking technological design idea. In a single, wordless moment, we witness a human being created in the same way a printed page is produced—the most disposable and replaceable object in our society, a material that costs next to nothing and is casually crumpled and thrown away. The metaphor becomes even sharper when we learn that new Mickey bodies are made from the spaceship’s waste and excrement. In a perpetual state of dim-witted serenity, Mickey does not care—he is the lowest form of life in the entire hierarchical structure.

Among Bong Joon-ho’s gallery of impoverished characters, he is the most wretched of all—a body at the disposal of power. As in Snowpiercer, he lives in environments completely different from those of the elite. In that film, social inequality was conveyed through design, with one of the most striking moments being the progression from the soot-covered, grimy world of the poor to the vibrant, colorful spaces of the front cars, whose existence seemed almost unimaginable. Similarly, in Mickey 17, the quarters of the ship’s leader are vibrant and richly decorated, while the working-class sections of the spaceship are dark, defined by shades of gray and black.

This contrast may seem conventional, but the film’s true innovation lies in subverting the common assumption that clean, minimalistic design signifies wealth. In Mickey 17, it is the rooms of the poor that feature geometric, minimalist designs, with clean lines and sparse furnishings. Conversely, in a reversal of Parasite, the rooms of the rich are colorful, baroque, and opulent, with an antique, neoclassical style—chandeliers, carpets, silverware on the dining table, and all the trappings of past wealth. Their power is inherited, steeped in tradition. They are not nobility, but the concept is the same: they are wealthy and powerful by ethnicity and lineage. In this new world, social hierarchies have openly reverted to those of the 19th century, stripping the lower classes of history and identity through interior design—because without a past, they matter even less.

Mickey embodies the ultimate expression of the pastless individual, forever stuck at the same age, dying and resurrecting endlessly without any religious undertone. In fact, quite the opposite. Fortunately, his double turns out to be angrier and unwilling to accept this new reality. This sparks a kind of rebellion, joined by alien creatures and others fed up with the rule of an ignorant, vaguely Trumpian overlord. The real insurrection begins only when the rich are defiled—when their pristine environment, their rooms, and their precious furnishings are tainted. The moment of true revolt comes when someone vomits on the Iranian carpet.

In this way, an idea—an ethical and moral concept—is not just conveyed through words but is reinforced through actions and imagery. The film does not merely instruct the audience; instead, it allows viewers to develop their own awareness by watching, piecing together the visual and narrative clues that Mickey 17 provides.

Opening image: © 2025 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. All Rights Reserved