20 November 2008 - 16 March 2009

RON ARAD TALKS TO MARIE-LAURE JOUSSET

of the design department at the Musée National d'Art Moderne / Centre Pompidou

MARIE-LAURE JOUSSET: No Discipline: we hesitated a great deal over these two words. In seeking a title for the exhibition, did we have to resort to concepts of 'indiscipline', 'non-discipline', or 'no discipline'?

RON ARAD: It's true that French and English are languages separated by two cultures, two different worlds, and that words and expressions can be contradictory. But personally, I'm very happy with the title 'No Discipline' for the exhibition. There's no need for definition. Concrete Stereo alludes to architecture (because of the concrete), and to music, and yet it's also a piece of design. 'No Discipline' is exactly that.

M.-L. J.: …to come to the concept of the exhibition itself, we have tried to reflect every aspect of your work, exploring three different avenues: unique pieces, industrial pieces and architecture. Are you worried that people will ask, 'Who is Ron? An architect? An artist? A designer?

R. A.: I hope people will say: 'He's a good architect, a good artist and good designer.' You know, when you go into the studio, there's no barrier between these functions, and you don't need a passport to go from one to the other. That's how I work, too bad if people feel a need to tidy things up and classify other people and things systematically. As I have said already, I like to have fun. I like it when people in an office feel as if they're at nursery school, when you don't start the week moaning about the fact that it's Monday. The idea of a playground, a recreation ground, is fundamental for me. I didn't plan to go into the world of design, I didn't do it on purpose... what happened was that I didn't feel comfortable working in an architectural practice. For example, when I made the piece that referred to the ready-mades – the Rover Chair – it wasn't because I wanted to save the planet by recycling, or because I wanted to get into furniture design, no, it was because at that time, I was able to do it. That's all.

M.-L. J.: It was within your means and capabilities, in a way.

R. A.: It was feasible, at any rate.

M.-L. J.: How do you use colour in your creations?

R. A.: I adore colours: the colour of metal, copper, cement, wood... What I don't like is using paint to introduce colour into what I do. On the other hand, I don't adhere to struct rules like: 'Paint is ugly.' I prefer to say: 'Let's talk about materials rather than using other materials to cover them up.' Nothing is ever completely simple. With regard to materials, for example: I love stainless steel, but not chrome. But if I needed to use chrome one day I wouldn't ban it, I would use chrome.

M.-L. J.: In essence, you don't apply or follow any particular methodology.

R. A.: No, I would describe myself as lazy, with no working method.

M.-L. J.: Lazy?

R. A.: In my own way. Which basically means counting on the people around me: and since I'm surrounded by extremely competent people, I lean on them. Before I design anything, I talk things over with them. It's my most effective tool. But I tend to skip between one idea and the next, I'm quite capable of dropping everything and moving on to something completely different. When the Rover Chair became a success for us, I stopped making it because I didn't want it to turn into a facile process. In fact, everything took off very quickly after an article in Blueprint magazine. A fan of the chairs, who I didn't know me from Adam, said I was London's most interesting designer. And at the time, I was far from thinking of myself as a designer.

M.-L. J.: Once, you said something which I found quite surprising: you said, 'I have an imaginary museum in my head, and I know, love and appreciate Matisse, without possessing him.' What does this idea of 'a work in your head' mean to you? To have the use or enjoyment of it, in a way, without being the owner of it?

R. A.: I owe a lot to museums. Beyond school, they have been responsible for part of my education. I didn't come from the centre of things, I came in to museums from the suburbs [?]. I saw a huge Van Gogh exhibition in that way, and a Giacometti exhibition. These things mark a child, or an adolescent, adventures like that! And so yes, when people comment on the high price of works of art, my response is that you can be a consumer of art, you can enjoy it without buying it. Recently, again, when I went to the fantastic Giacometti exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, I never once asked myself: 'And that work there, how much is it worth?' No, I see myself as a consumer of the things I see, without feeling the need to buy them.

M.-L. J.: But that doesn't stop your own creations from having a certain value?

R. A.: When you see the price that something you've made can fetch, then naturally it gives you an idea of the value of your works, and helps you to situate them in relation to other people's work. But there are abuses of the system: I see a lot of work today that's done cynically, based on what the market wants. And then there's the paradox of this market that tells the art market that the 'art of design' sells well, when at the same time, the art world doesn't accept design... For me, it's just a question of marketing. In any case, I don't find it very satisfactory to talk about design as art.

M.-L. J.: Some would accuse you of being the originator of the phenomenon.

R. A.: If that's true, I didn't do it on purpose.

M.-L. J.: Generally speaking, is money a major issue in your work?

R. A.: It allows me to do what I do. I should say that I've been lucky from the start, to be able to finance my activities through my work. I've never had to go fishng for finance. Even if, today, with a team of 20 people working with me, we're more comfortably off than we were before, we would obviously like to have more money, to launch more projects.

M.-L. J.: To end, I'd like to say how much I have enjoyed working on this exhibition together. It's been an emotional experience for me, reflecting my own journey almost exactly: I started out with you, among others, working on the exhibition Nouvelles Tendances and I'm ending with you, now. This will be my last exhibition. I feel very touched by that.

R. A.: What I showed here twenty years ago wasn't really design. It was much closer to Caesar and Chamberlain than to Marcel Breuer and Charles Eames, even if the first works to destroy were armchairs by Eames. Today, finally, I wonder if I'm not what might be called a 'special case'? Am I able, or unable, to make things in the way people would want me to make them, to do what is expected of me.

Interview by Marie-Laure Jousset, in London, June 2008.

PHOTOS

Bodyguard, sculpture chair 2008

Editor Gallery Mourmans, Maastricht/Timothy Taylor Gallery, London

© Timothy Taylor Gallery

Table Paved With Good Intentions, 2005

Editor Ron Arad Associates, Londres

© Emmanuelle & Jérôme de Noirmont

photo Mathieu Ferrier

Southern Hemisphere, sculpture chair 2007

© The Gallery Mourmans

photo Erik & Petra Hesmerg

Bodyguard n° 2, sculpture chair 2007

© The Gallery Mourmans

photo Erik & Petra Hesmerg

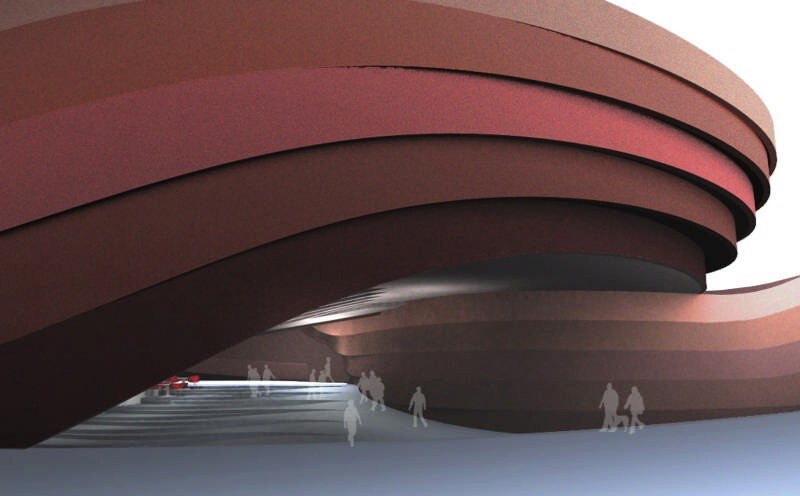

Design Museum, Holon, Israël, 2004,

work in progress.

© Ron Arad Associates

Hôtel Duomo, Rimini, Italy, 2003-2005,

completed project

© Ron Arad Associates