This article was originally published on Domus 605, April 1980

House like me

Somehow our own relation to specific events and images in time appears to be focused upon certain haunting disparate fragments of our experience, we are both observer and participator as in a game of billiards; we hover over a fixed field lit by a circular lamp; contemplating; establishing angles; then poise; calculate; hit; then hope. The fact that we come out of a darkness, knowing that the field is rather a given, and that there are three spheres (two white; one red); at first silent; waiting; dense compact atoms of past histories; and future histories too; set into motion by our will; our willingness to act upon those spheres; playing off the rigid-angle cushions; hitting the edges; hitting the multi-points of ends of the primary diameters; bouncing a few images and even fewer ideas into the stage and arena of a seemingly perpetual moment; caught in the stop-frame of a generation; anticipating some kind of illumination.

I remember one evening back in the late nineteen forties (when there were still trolley cars moving through snow on frozen tracks in New York) that I first came upon two images, both being in Italy outside of Rome; of a place begun but not finished called “Terza Roma”. Two photographic images which even today haunt; give one a chill; yet fascinate as certain strange unfamiliar landscapes do; which we sense to be mysterious and foreboding; seductive; and dangerous. It is the seemingly bucolic which disturbs. One photograph was of a pastoral landscape with sheep grazing within a field; in the distance a tall white building officiated, made up of floor upon floor of arches in series. The scene at once enticing and softly menacing. Only much later did I understand its surreality; its de Chiricoesque genealogy.

The other photo image was shot from a low angle focusing up upon the white arch structure as detail; heralding the rising of a marble horse; hoofs raised; fixed to a pedestal; the morning light increasing the depth of shaded volumetric muted concavities enclosing one or two stone figures within the empty central building; perhaps surrounded by dense clouds; separating it from the night; all subjects having a luminosity; an iridiscence; filtering through a sepia mist; at once releasing a nostalgia and a leaden dread.

![Domus 605 / April 1980 page details. Left and right, <em>Terza Roma</em>, Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana [Italian Civility Palace] by Guerrini, La Padula, Romano. Centre, <em>Terza Roma</em>, Palazzo dei Congressi [Congress Palace] by Adalberto Libera Domus 605 / April 1980 page details. Left and right, <em>Terza Roma</em>, Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana [Italian Civility Palace] by Guerrini, La Padula, Romano. Centre, <em>Terza Roma</em>, Palazzo dei Congressi [Congress Palace] by Adalberto Libera](/content/dam/domusweb/en/from-the-archive/2012/07/21/adalberto-libera-s-villa-malaparte/big_389480_3980_2429.jpg.foto.rmedium.jpg)

Two photos expressing evacuation; an excavation; yet instead of earth being removed it was the air brushed away. Whereas in Ostia Antica the fogs moved over the paths, here in “Terza Roma” the atmosphere froze into crystals of a pointless gravure. Whereas Ostia Antica was a romantic archaeological ruin in the earth; “Terza Roma” was an ideological ruin upon the earth; one devoid of distant celebrants; the other of not so distant furies. Two photos expressing a past disaster and indicating a future warning. A place of theater where the actors had long since disappeared; yet the stage lights had been left undimmed, undiminished; forgotten.

Since the initial inspection of the two photographs it was not more than five years later on a Sunday morning in 1953 that my wife and I approached the actual “Terza Roma” by bus; it still had the sense of a place waiting; of an irresolution. We walked towards the central monument, the building of vacant arches. We felt that the early photographs were more essential; more impacted; they had tolerated no interception. A scale had changed; the three-dimensionality exuded a vacancy. The materiality bleached the light. There were echoes of a construction going on to the West. A church was being built. A dull hammering impregnated the air. “Terza Roma” was waiting for an adjustment.

Our eyes caught another structure, a large white horizontal with a cube perched on the roof capped by a shell. It appeared like a stationary ship. We were drawn to its silent presence. There were no people about. The doors of this immense edifice were closed but unlocked. We entered into its inner silences and were confronted by an empty hall many stories high; clamped by criss-crossing stairways ascending to a roof-terrace-promenade which overlooked a melancholic countryside; the roof supporting an outdoor cascade of stone horizontal step-seating which held imaginary audiences, backs to the campagna; and imaginary contoured faces forward towards a voided stage; it was in shadow. The eeriness of that moment was compressive; devastating; unsettling; we were pulled into its speculations; a total modern theater; no players; no audience; only the drum of jack-hammers far away drilling into quarry caves. Sometime later we were informed that the theater-exhibit building was designed by an architect by the name of Libera...

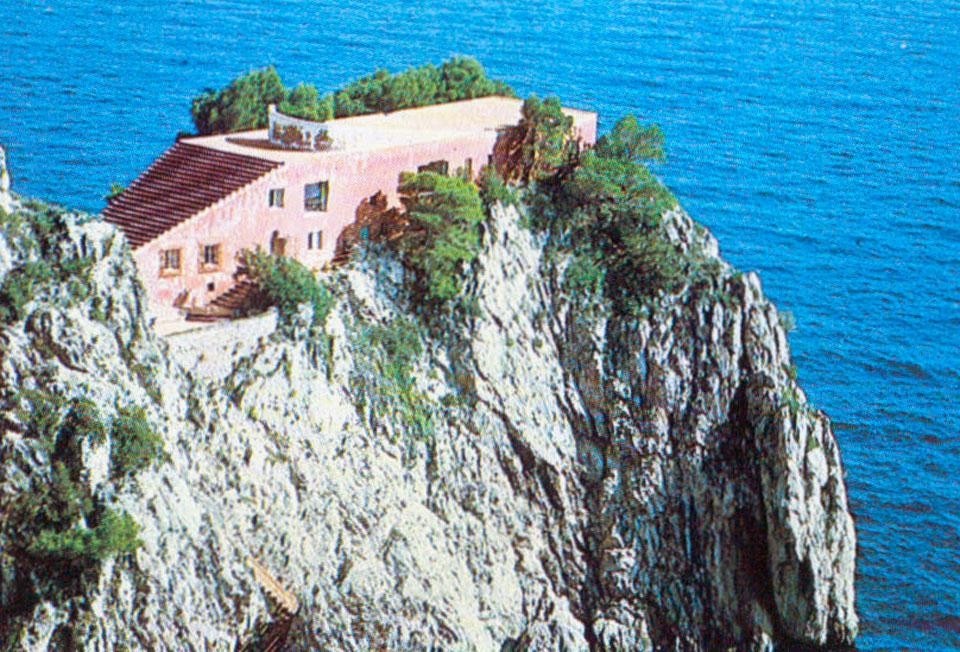

Libera’s Malaparte house is private. It is a house of paradoxes. It is an object which consumes. It is filled with unrequited histories. It is a relic left upon the pinnacle after the seas have subsided. It is a sarcophagus of soft cries. It whispers of inevitable fates

I often wondered about him. The following Sunday we made a sad journey to another monument also outside of Rome called Fosse Ardeatine. This was a grave site of over a hundred tragic Italian souls who were rounded up during World War II by the Germans, herded into the Ardeatine caves and machine-gunned to their deaths. The victims’ ages ranged from 17 to 80 years of age. One entered through agate of metal and into the labyrinthic caves. We could still see the holes upon the cave walls where the gun shells had entered the earth; there were some candles lit. The anguish of this place left the mind stunned. After the caves you entered under a hovering mammoth concrete slab raised slightly above mounded earth for the filtering of a soft light. Under the compressive slab were placed stone sarcophagi seemingly unending in number and upon each coffin was placed a photo of the deceased.

All the above memories are in a way an introduction; preceedings brought forth by a transatlantic phone call from one of the editors of Domus. The inquiry was whether I knew the “Malaparte house” which I answered yes to. Another inquiry was whether I knew of the architect Libera. Which I answered yes to. Did I know that Libera was the architect for the house? That I did not know but I could imagine it to be so. The last inquiry was whether I would do an essay on the house. I was not sure I would. Malaparte was for me a clouded figure, there was a darkness there, one felt uncomfortable. Libera was always disturbing, yet the image of the outdoor theater in “Terza Roma” always provoked.

Why out of the blue would I receive a call from Milan in 1980 asking me to write on a house designed by Libera in 1940 for Malaparte? I could be some sort of detective and search into the past of Malaparte? Libera? Domus? I decided to let it simmer and awaited the promised photos and plans of the Capri house. That there was some kind of sorcery going on I did not doubt for a minute. Was I to be some medium?

The photos and plans did arrive and they accelerated a decision to attempt to unravel some curious interconnections, architectural specifically, yet... Malaparte’s house conceived by Libera is a house of rituals and rites, it is a house of mysteries, it at once brings forth the chill of the Aegean on the horn head of past sacrifices, it is an ancient play placed in an Italian light. It has to do with the primitive gods and their unrelenting demands.

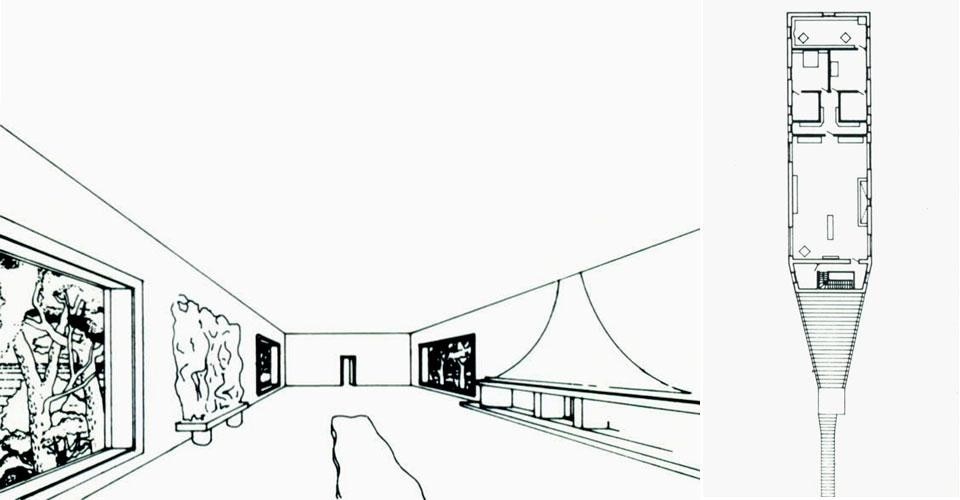

It has to do with the suction of leaves and stone and the expulsions of sea and sky. It has to do with the choice of good and evil and the inevitable pathos when a wrong choice is made. It has to do with the hollowness of caves and the inaccessibility of the sun. It has to do with the abandonment of abstraction and the seduction of the lyrical. It also has to do with the dilemma and problems of our own time. The plan of the house is most ambiguous. It may be a description of a program and it might not be.

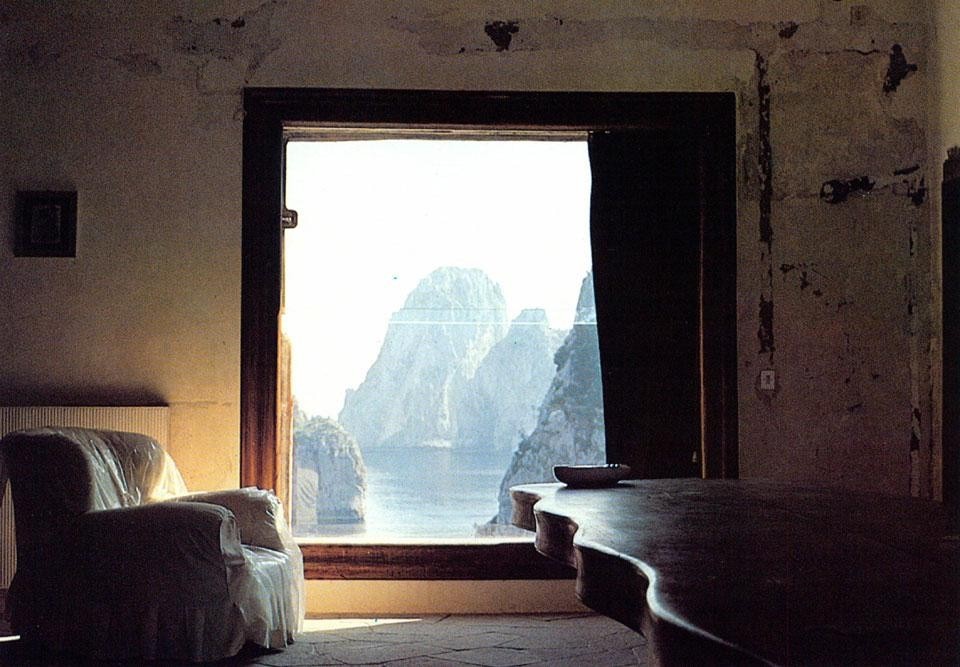

It reminds one of something from pre-Christian ages; yes, that is it. The plan is really an elevation of one of the wood Egyptian burial paddles placed in the tomb of a Pharaoh against the wall of his last resting place. It has a diminishing handle sometimes wrapped by ropes and on the paddle flat itself are various signs and symbols telling of the leader’s life, his triumphs and... The plan of the Malaparte house is an inscription. One cannot find the entrance to this house, it is hidden like the tombs. Assuming some entry, once inside according to the two perspective drawings we have entered an underground world four windows upon two walls a view out to a submerged ocean bottom; we are in some kind of exploratory submarine moving through the stalactites of a dark surface; we are warmed by an illuminating fireplace on one side and Dante-esque figures of limbo on the other; at the far end a singular door beckons. Libera then makes a perspective of the door silently opening onto a corridor at the end of which are two doors ... one good? One evil? The choice is ours as in the courtyard of the Alhambra in Granada.

This simple perspective is impregnate with meaning. We are challenged to enter further labyrinths leading to a “no exit”. The final room containing on axis a window overlooking, the horizon line, an inaccessible horizon line, the membrane where sky and sea meet. We see it, yearn for it, but we cannot touch it. Dare we tread our way back? The two line perspectives are signs of our “passage”, precise without quarter, didactic final. In the middle of the major “living room” floats a biomorphic slab.

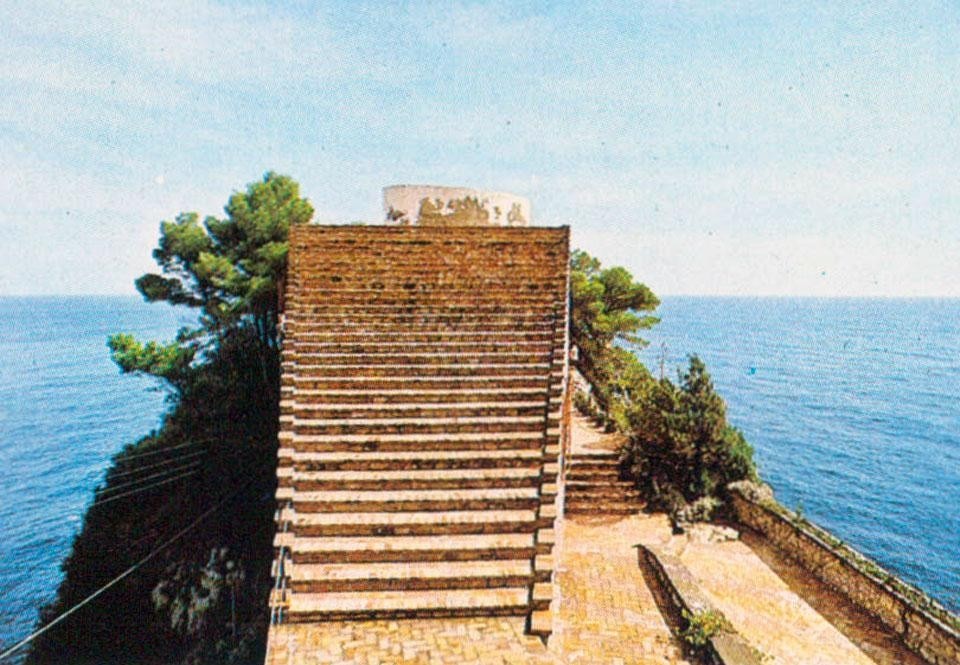

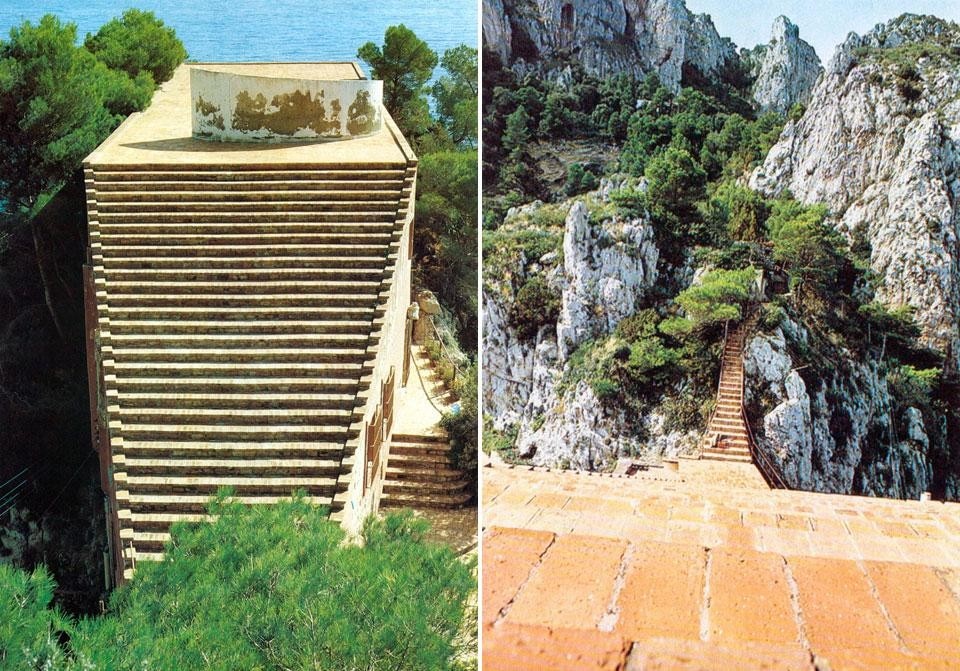

Upon expulsion from the depths one passes this centralized floating amoeba. It awaits. The exterior drama is panoramic and of another quality. It is a drama of man and nature, birth and death, expansion and compression, sacrifice and acceptance. The major primal element is the rising exterior stairway which ends upon the flat plane of the roof-terrace; the stair serves a double purpose: it is access to the vision of sky and sea, and upon one’s descent, going back, the stair acts as the seating for a theater, setting the imaginary audience’s backs to the horizontal horizon line of the sea, their eyes focusing on a diminishing vanishing point which disappears into a dark orifice garlanded by plant and rock. It is the observation of nature’s womb from which we formally entered the play of our life and it is the opening which receives us in our final exit.

The roof-stair-theater seats is of a funnel shape, narrow at the bottom expanding as we rise. The perspective is distorted, the lateral is emphasized, geometry has been warped. If we arrived upon the flat plane roof and if the roof did not contain as it does a curverlinear wall, our sense of uneasiness would not be so fearful. So the stair leads up to a sacrificial horizontal. We see that on that plane is an enclosure. What lies behind it? The most fearful, a nothingness, an enclosure that encompasses a void. We are in the midst of ancient rites. Libera has set the stage for an awesomeness. Man is infallible and temporal.

Libera’s Malaparte house is private. It is a house of paradoxes. It is an object which consumes. It is filled with unrequited histories. It is a relic left upon the pinnacle after the seas have subsided. It is a sarcophagus of soft cries. It whispers of inevitable fates. The “House” and Libera’s other monument, the “Terza Roma” theater-exhibition building, are shipwrecks upon the waters of a chaotic time, yet are dramatic, powerful, sad, nostalgic, as all shipwrecks are, they imprint forever upon one’s mind... and raise disquieting questions...

John Hejduk, New York, 1 January 1980