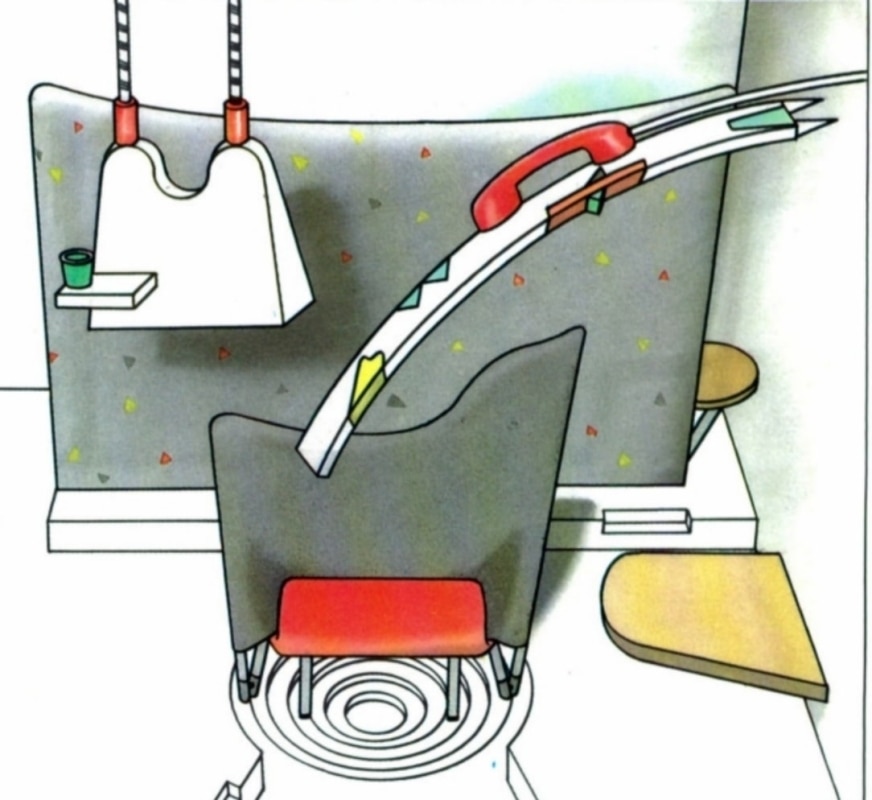

Played out in just a handful of episodes – always poised between the visionary and the playful – the Telematic House (Casa Telematica) is a design story that traces the arrival of technology and the immaterial within the domestic realm. Its protagonist is Ugo La Pietra, designer and experimenter who perhaps more than anyone carried forward the research and provocations of Italian Radical Design. As early as the beginning of the 1970s, with the MoMA exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape as horizon, La Pietra had already developed the concept of the Telematic House as a spatial device designed to expand the perceptual possibilities of the individual. At that stage, it remained a symbolic and abstract volume: a triangular section space, evocative of the perfect-form ideal. A decade later, in 1983, the project took on a strikingly different guise. At the Milan Fair, in a show curated with Franco Bettetini and Aldo Grasso, once again under the same title, La Pietra defined the Telematic House as an “experiment in verification and contamination between growing electronic memory and the domestic space.” The Telematic House of the ’80s was the home of information’s pervasiveness, of life shaped and directed by screens, as omnipresent as Piano and Rogers had imagined for the Pompidou in Paris, yet here integrated directly into the furniture itself.

La Pietra’s idea of living is perhaps best revealed in that famous moment when he recently invited Domus into his own home. But equally revealing are his frequent presences in the Mendini-era Domus: one such moment, where the Telematic House served as a lens through which to explore the future of domestic furnishings in the 1980s, was January 1983, in issue 637.

It's always armchair time

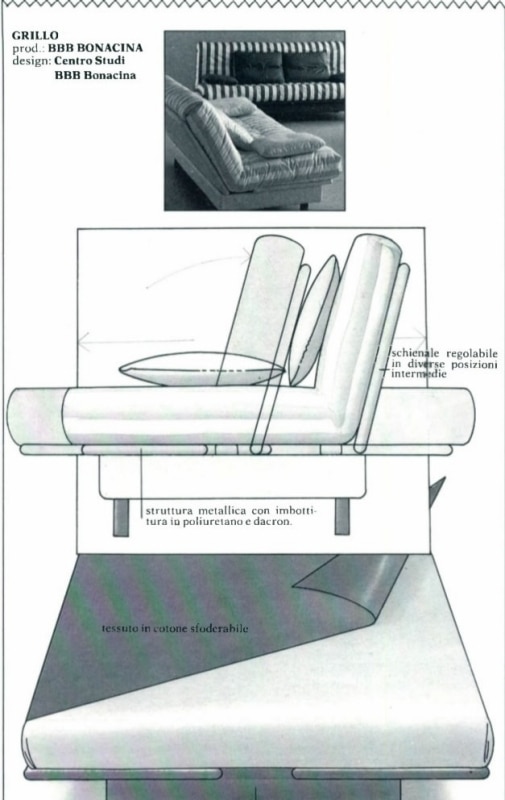

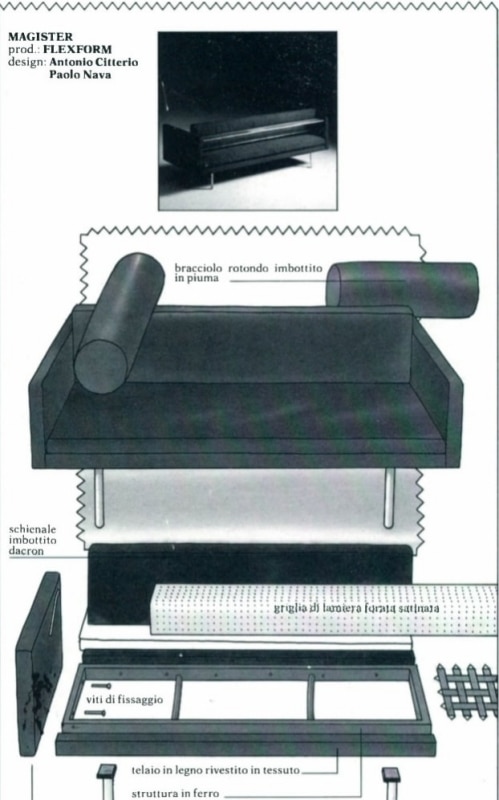

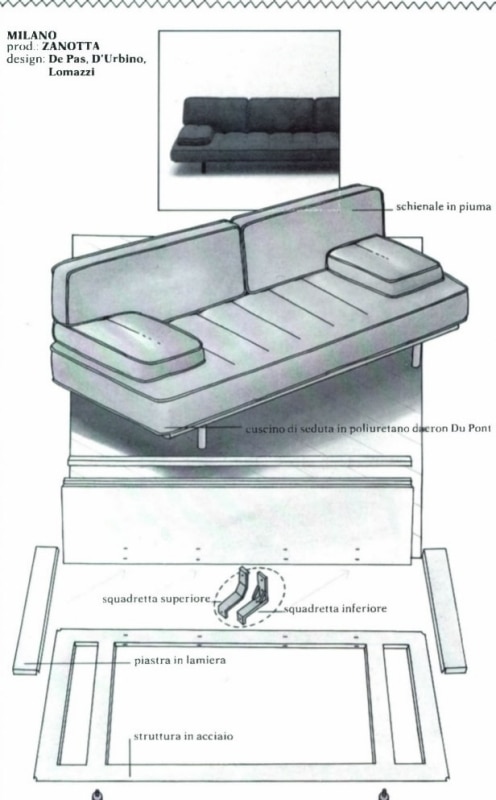

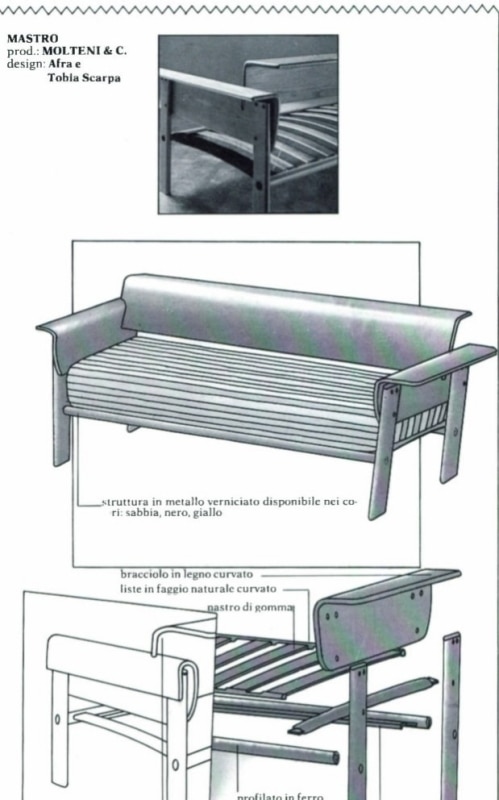

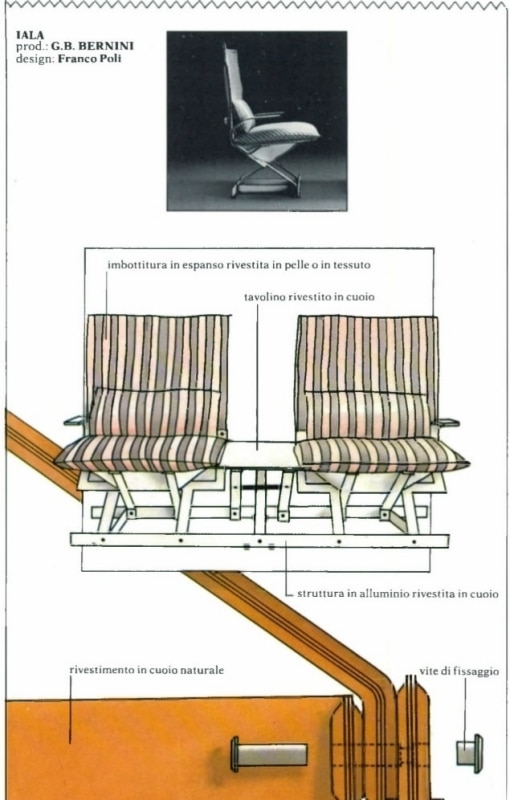

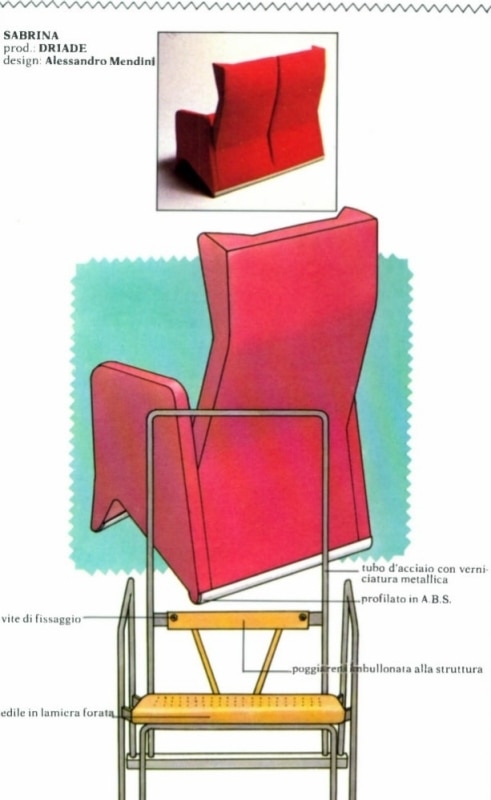

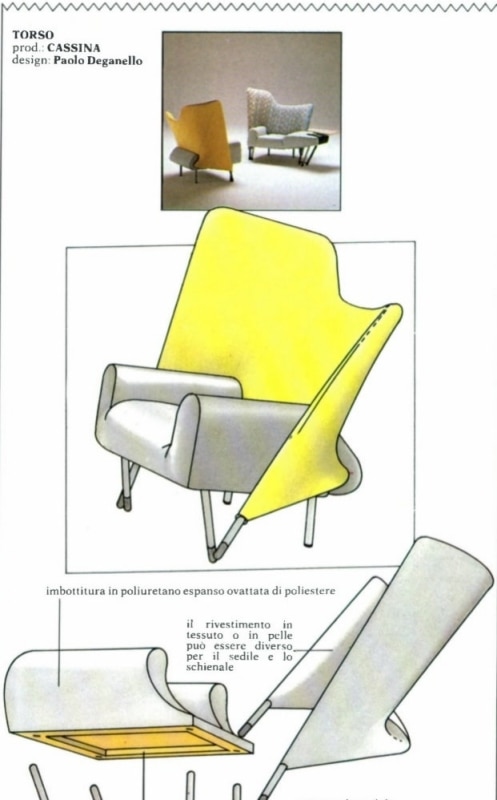

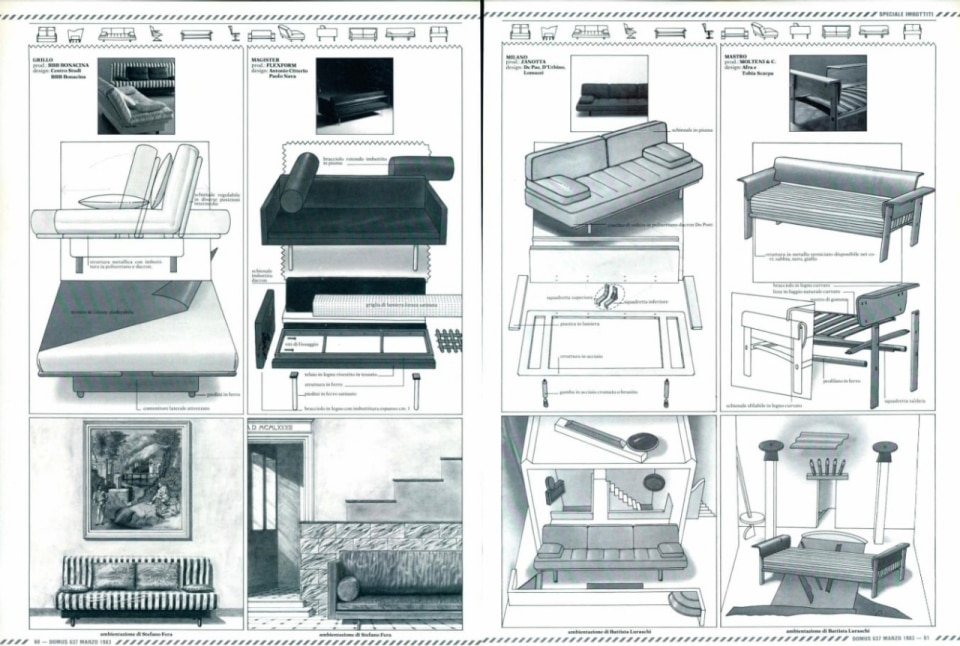

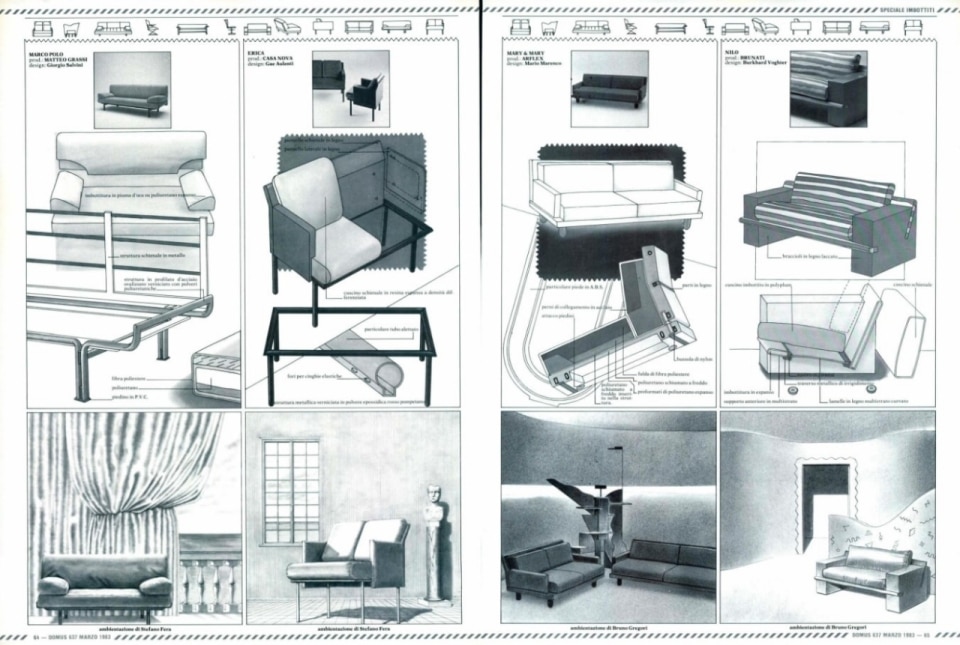

The revival of past rituals and the creation of new ones stimulates the continual development and updating of the “soft object” for the house.

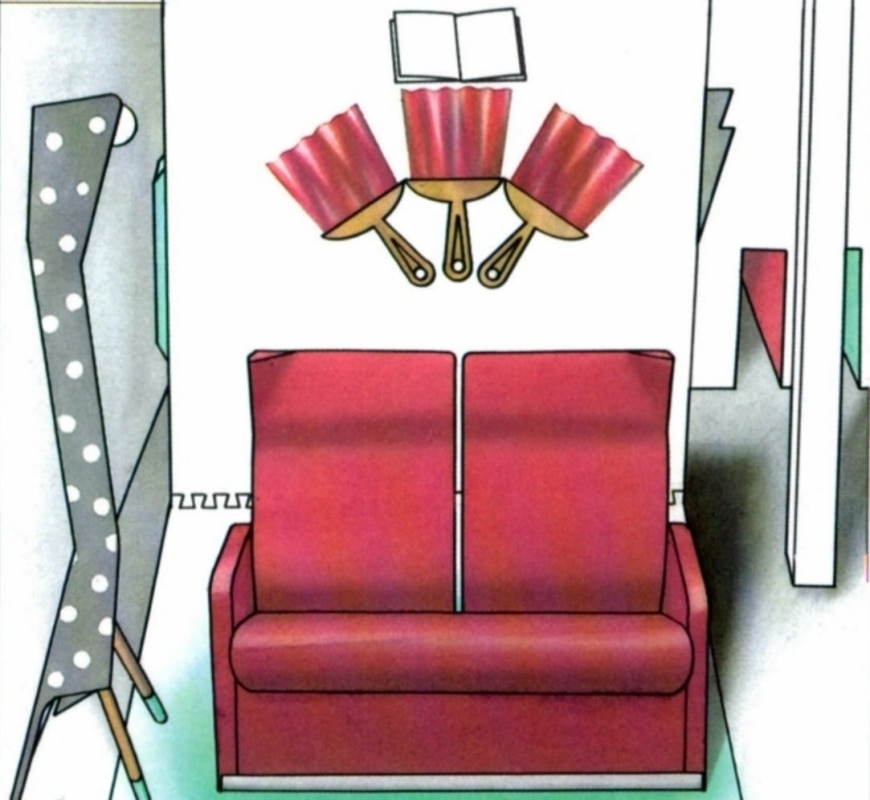

Armchair, two-seater settee, three-seater, corner lamp, little table “fixed” in the centre, an expression of the ritual of conversation while taking tea (or coffee, as you prefer). Exchanges of information in “salons” of a “serious” kind, the “few cups of tea” with the ladies: customs that would seem to be disappearing day by day.

And yet the objects that define the rite are still basic elements of today's domestic space: “600 drawing rooms, 400 bedrooms, 350 kitchens” are on offer in advertisements for one of the many furniture supermarkets on the outskirts of Milan.

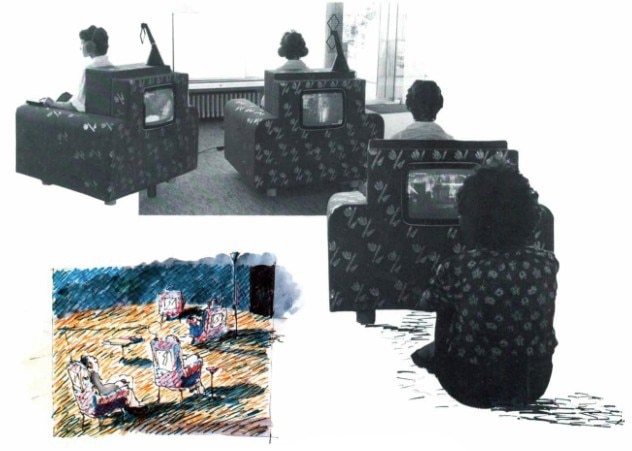

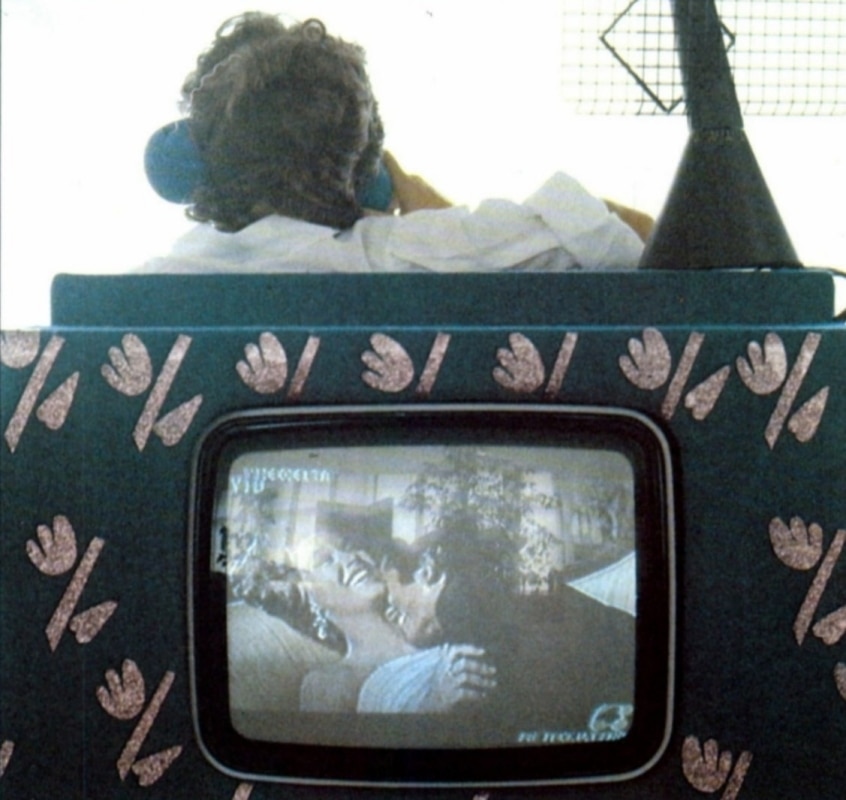

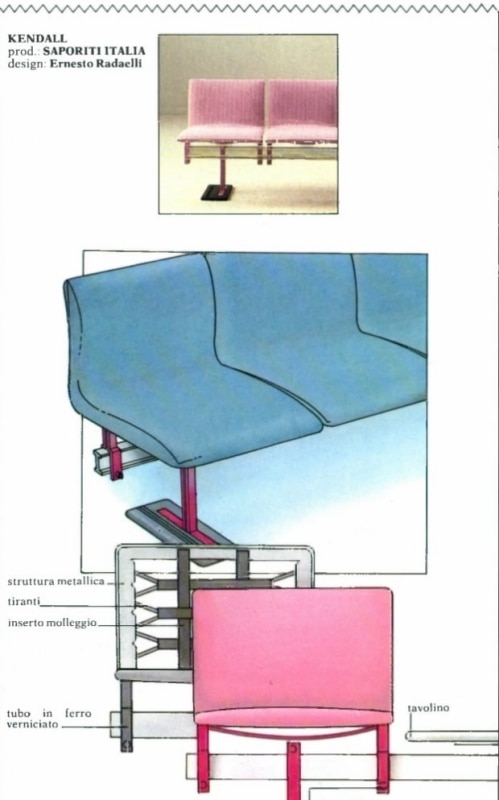

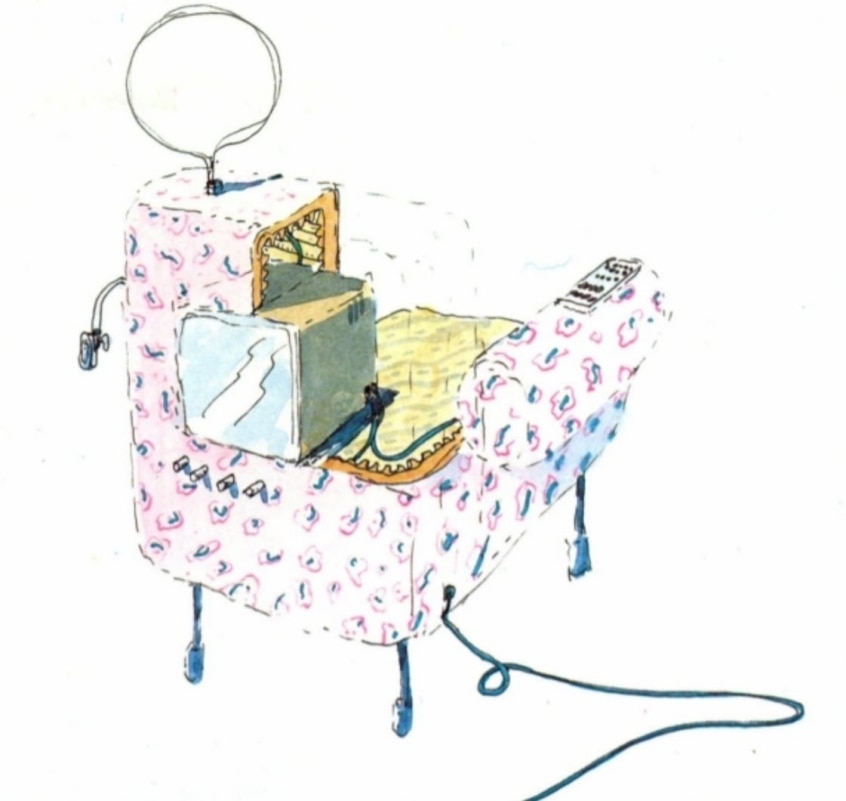

The armchair is still an important object, important for the manufacturer, for the designer and for the consumer. Companies specializing exclusively in upholstery continue to grow in size and in numbers, designers both old and new sooner of later tackle this “soft object”; the consumer's need for it continues to increase. Sometimes they need it for a rather artificial recreation of the old centralized sitting room (like those you often see in IV commercials) aiming perhaps to give a physical embodiment of the old ritual, more frequently for the purposes of new rituals like those linked to new information and communication technologies.

We will see the centralized arrangement disappear in favour of a unidirectional organization towards the single large TV screen.

Ugo La Pietra

So it is that the armchair finds a new lease of life, singly or in pairs, influencing other elements or being influenced. It will probably continue to be a basic element in our domestic environment for a long time to come.

Informatics and telematics in the home? All right: the armchair is always available!

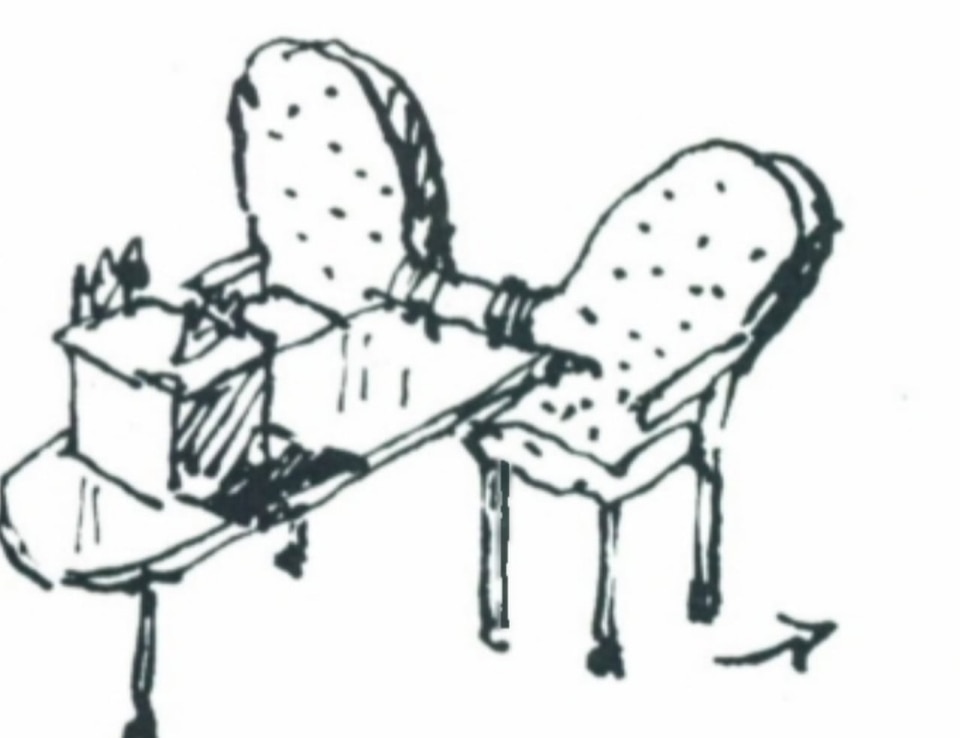

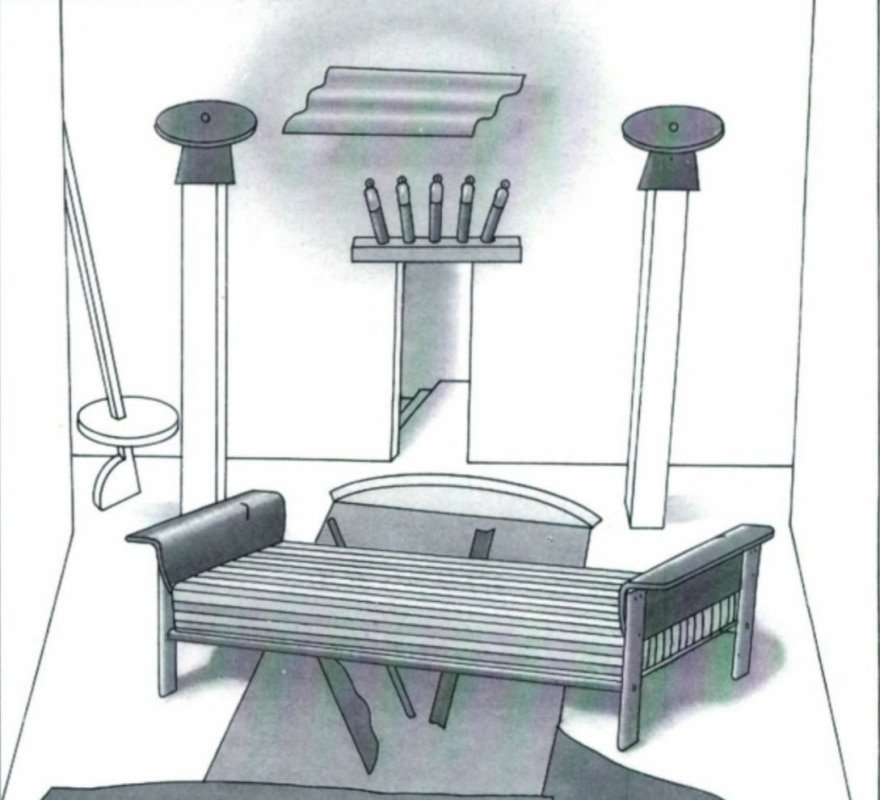

We will see the centralized arrangement disappear in favour of a unidirectional organization towards the single large TV screen, but the armchair may combine with new instruments in new forms and combinations. Maybe a single small armchair for videogames, a double swivel armchair for two-person games (computerized chess), chaise-longue for the reading of personal data, armchair terminals with monitor incorporated, slung above, alongside, or clipped on.