Architect by training, storyteller by vocation, Cesare Casati (1936–2025) was a pivotal figure in both Italian and international design culture. His relationship with the design realm was total: he explored it through buildings, cult design pieces – the Pills and Pelota lamps to name but two – publishing, and exhibition curating.

It's only natural to link his multidisciplinary approach to his early mentorship under someone who famously championed design as a passion: Gio Ponti. Casati began his career in Ponti’s studio, and it was Ponti who brought him into the Domus editorial team – Casati would later lead the magazine as editor-in-chief from 1976 to 1979.

Casati was deeply rooted in the present – a present always cared about participating and shaping. Under his leadership, Domus was an active participant in the cultural and architectural transformations of the era: one such transformation was the arrival of the Centre Pompidou, the spaceship of the information age that the young Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers were landing in the heart of historic Paris, following their 1971 competition win. Domus followed the Pompidou story closely over the years. But it was Casati himself who, at the moment of the building’s opening, interviewed Piano, Rogers, and engineer Peter Rice. The result, the first vivid narrative of a revolutionary project, appeared in the January 1977 issue, n. 566.

Through these questions from the long, comprehensive interview, we want to remember Cesare Casati for his strongest trait, while he is engaged in participating as a protagonist in the shaping of architectural history.

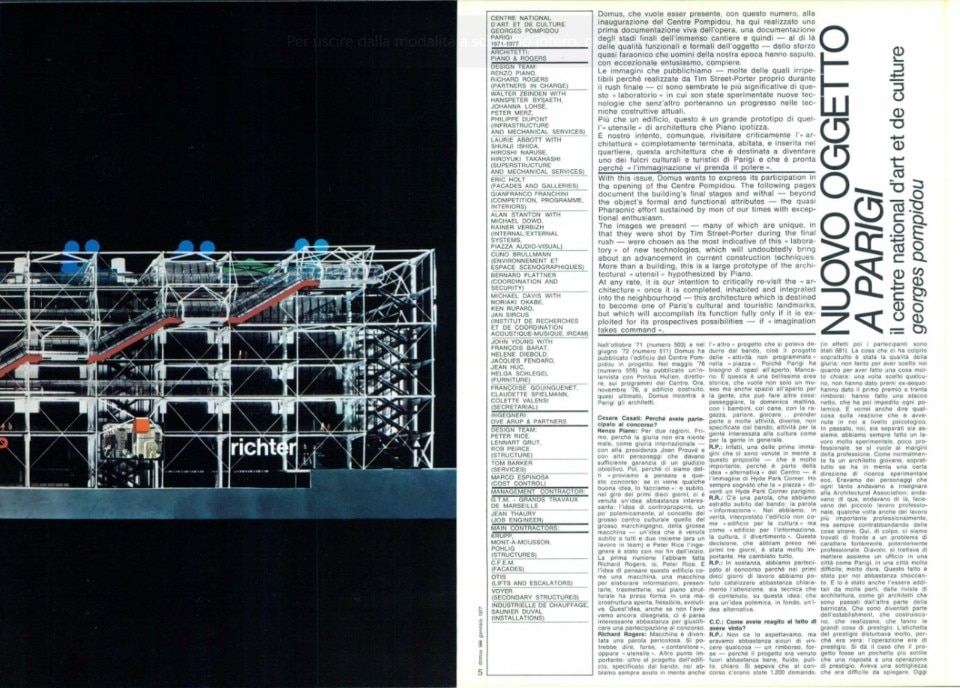

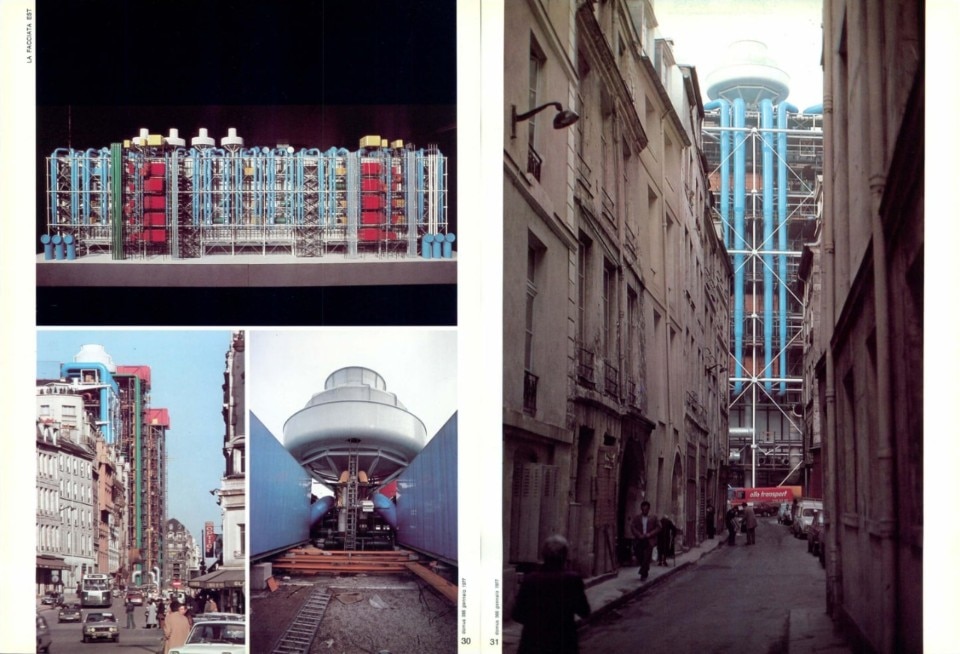

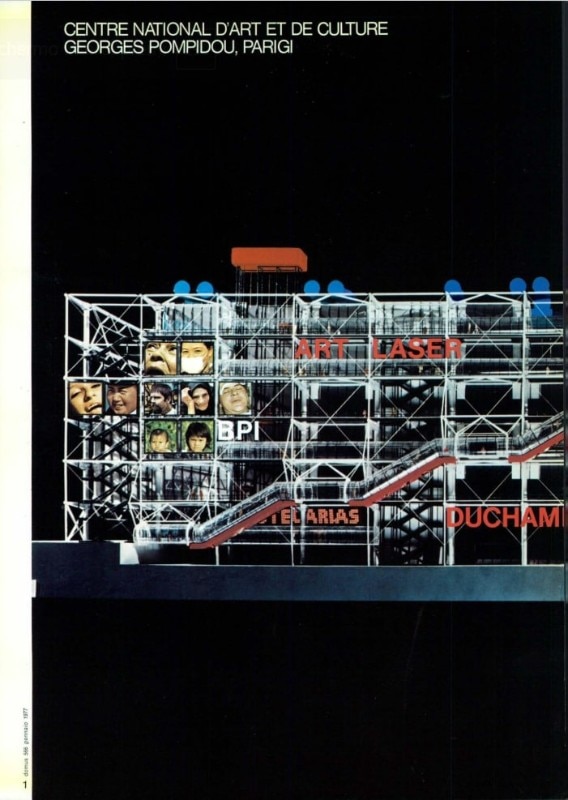

Nuovo oggetto a Parigi. Il Centre National d'art e de culture Georges Pompidou

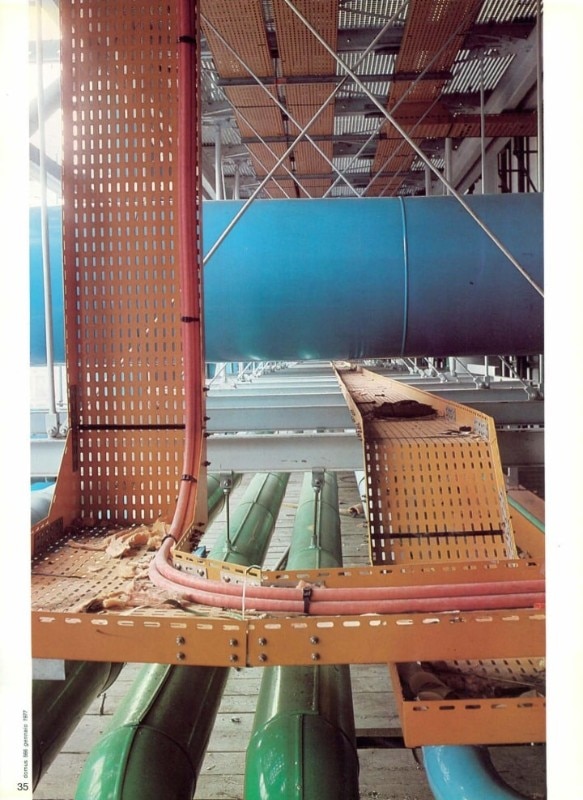

With this issue, Domus wants to express its participation in the opening of the Centre Pompidou. The following pages document the building's final stages and withal - beyond the object's formal and functional attributes - the quasi-Pharaonic effort sustained by men of our times with exceptional enthusiasm.

The images we present — many of which are unique, in that they were shot by Tim Street-Porter during the final rush - were chosen as the most indicative of this “laboratory” of new technologies, which will undoubtedly bring about an advancement in current construction techniques. More than a building, this is a large prototype of the architectural “utensil” hypothesized by Piano.

At any rate, it is our intention to critically re-visit the “architecture” once it is completed, inhabited and integrated into the neighborhood - this architecture which is destined to become one of Pariss cultural and touristic landmarks, but which will accomplish its function fully only if it is exploited for its prospectives possibilities - if “imagination takes command”.

In October '71 (number 503) and June 72 (number 511) Domus published the Centre Pompidou building project. In May 76 (number 558) it published an interview with Pontus Hulten, the director, on the programs of the Centre. Now, in November '76, nearing the building's completion, Domus meets the architects in Paris.

Cesare Casati: Why did you participate in the competition?

Renzo Piano: For two reasons. First of all, because the jury wasn't bad as an international jury, with jean Prouvé as president and other individuals who guaranteed a certain amount of objectivity; it was also a rather competent jury. Then, because we said to ourselves “Let's try and think about this competition: if we get a good idea for it we'll do it”: and immediately, within the first ten days, we had quite an interesting idea: that of counter-proposing, in a slightly controversial vein, the concept of a big contraption, or machine, to that of the large cultural centre - an idea we both had simultaneously, it was team work, and Peter Rice, the engineer, was with us from the very beginning. The first meeting was between Richard Rogers, Peter Rice and myself. And the idea of seeing this building as a machine, a machine to elaborate, present and transmit information on a structural level, took shape in an open, flexible and evolving macrostructure. This idea, although it hadn't been drawn yet, seemed interesting enough to warrant our participation in the competition.

Richard Rogers: Machine is a dangerous word now. It's like organic architecture. Instead of machine, one could probably say «container” or «utensil». A utensil and a container.

Another point we decided very early on is the following: besides the brief, or program, as given by the competition, there was another piece which we have maintained all the way through, which was not written in the brief, but which could be added to the brief and this we termed the non-programmed activities, which consist of the “piazza” - the fact that Paris needed open space. We very quickly realised how tight this area was, and that its a very beautiful historical area, which created a need not only for a museum but also for a place for people in this area to do other things: a place to go to on Sunday morning with children, with dogs, with girlfriends, or to go and play, to go to all manner of activities not specifically stated in the program. It became something in which both culturally oriented people and the public could participate.

R.P.: As a matter of fact, one of the first images that occurred to us in this respect - which is very important, because it is part of the “alternative” idea for the Centre - is that of Hyde Park Corner. I have always dreamed of this piazza becoming the Parisian Hyde Park Corner.

R.R.: The word which most stood out of the brief was the word information. As a matter of fact, from then on, we changed the meaning from (I think it was called) “building for culture”, to a “building for information, culture and entertainment”. I think this is a very important decision that we made practically during the first three days. And it gave us a totally new interpretation. It was no longer a closed monument to culture, but rather totally new interpretation. It was no longer a closed monument to culture, but rather information and entertainment as well as culture.

R.P.: Fundamentally, we participated in the competition because in the first ten days of work we were able to catalyse quite clearly the attention, both in terms of technique and content, on this idea, which was a controversial and an alternative idea, in the end.

C.C.: What was your reaction to having won?

R.P.: We weren't expecting it, but we were pretty sure of winning something - a reimbursement, perhaps - because the project turned out very well: it was flowing, clean and clear. We knew that the competition had had 1.200 requests (although in the end there were only 681 participants). What struck, us most was the quality of the jury: not so much for choosing us, as for something they did: having made their selection they did not give out any ex-aequo prizes: they gave one prize and thirty reimbursements: they created a clear distinction which did away with all potential controversy and with all possible discussion as to whether three or four proposals should be put together, which would have been the end of the project. But now, I would like to say something about our psychological reaction. In the past, both individually and collectively, our work was very experimental and not very professional, let's say, on the margins of the profession, all of which is normal for a young architect whose approach is essentially experimental and on a research level. Every now and then we taught at the Architectural Association, we went everywhere mostly handling very small professional jobs, but sometimes even jobs that were more important on a professional scale, yet always smuggling in strange concepts. And then, all of a sudden, we were having to confront a problem whose premises were entirely professional. Hell, it was a matter of setting up an office in a city like Paris, which is a very difficult and hard city. All of this was quite shocking for us, as was the fact that we were being singled out on all sides, by architectural magazines as architects who had changed ranks and who had become part of the establishment, architects designing and building projects of enormous prestige. The label “prestige” was particularly disturbing in that it was true, this was a prestige operation.

It just so happens that the project was more subtly conceived than as a mere response to an operation of prestige. And this subtlety was difficult to explain. It has now become apparent in the building -itself. At any rate, we weren't that scared after all. We decided immediately that with something like this, you either do it or you don't.

Besides the brief, or program, as given by the competition, there was another piece which we have maintained all the way through, which was not written in the brief, but which could be added to the brief and this we termed the non-programmed activities, which consist of the piazza

Richard Rogers

C.C.: How did you organise yourselves?

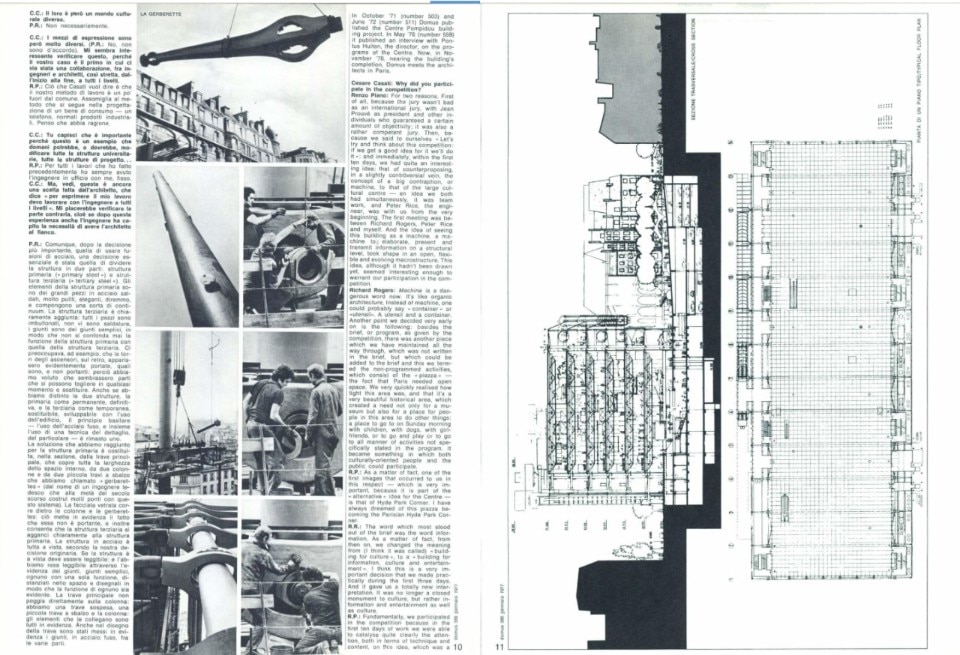

R.P./R.R.: The way in which the profession is practiced in France - and this is not intended as a nationalistic issue - was very different from what we were accustomed to in Italy and especially in England. In France it is unthinkable that the architect who has designed the project should also coordinate the entire operation. Normally in France, according to Beaux-Arts traditions of long standing, the architect is someone who would initially make a more or less detailed sketch which would then be handed over to the «bureau d'étude”. which is not even an engineering office in the anglo-saxon sense, but rather an office which handles operations of an administrative order, that is the “appel d'ordre” or contracting.

And then, finally, and this is typically French, all of the work including the actual authentic project to be used for construction, is done by the contractor. The contractor inherits the architect's sketches, the “pieces écrites” of the “bureau d'étude” and finally does the real work... There is no control. This procedure, which on top of everything else increases costs enormously, was the first thing we came up against in France. The contract which had been submitted to us initially, reflected this type of structure. We realised immediately that it was impossible to do a building as subtle and complex as ours following that kind of procedure.

So we immediately put through two important operations: we joined forces with Ove Arup & Partners, who had won the competition with us, and together, we set up an office in Paris; then we started a long battle with the client in order to obtain a particular type of contract, and we succeeded. A ministerial decree had to be obtained before this contract could be sanctioned. This was an historical event because two years after the decree, a reform of the system of design for public institutions was passed. According to this reform, it is the architect, as “maitre d'oeuvre», who is responsible for quality, planning (in terms of time limits), and also costs. Should he neglect any of these, for instance exceeding the projected budget by more than 12%, he is penalised. Consequently, we organised a well-integrated office putting together architects, engineers and especially (this is the most important thing). what in France is known as “contractant principal” and what in anglo-saxon countries is known as “management contractor», that is, a large contracting firm, selected by us, which lent us its brains to help us professionally in contracting operations: organisation of the building site, installation deadlines, etc. The contractor came to our aid as a professional body rather than as a constructor.

The organisation of the office has been fundamental. At times, the office counted nearly one hundred people. Initially, there were 30-40 people, then 100 including architects, engineers, and the «contractant principal»; and even right now there are at least 60-70 people. An office whose scale was made possible by a particular type of contract and consisting of a team which was able to control the operation in its entirety. The “quantity surveyors», an essential part of this team, were exclusively in charge of costs and contracts: they have a function similar to that of engineers, working very closely with the architect and the structural engineer to coordinate all the data. The quantity surveyors team, at one point: made up of a dozen members, now I reduced to 6 or 7, has played a very important role. We have also had consultants from all parts of the world: Holland, Germany, America, etc. Our office was in itself very international: in a group of 26 architects, there were 1l nationalities. A pretty mixed system. And we design ed everything. every single bolt: we have produced 20-25.000 drawings. We have been in Paris for six years although we maintained our office in London.

C.C.: How did you organise the building site?

R.P./R.R.: The organisation of the building site was part of the project. From the very beginning, it was decided that the project's underground section should be built on site, while at the same time, its prefabricated section would be produced in the plants, so that when the cement construction reached surface level, the prefabricated units would be on hand and ready to be installed. In synthesis, this was a construction where everything was done “simultaneously”. Another thing we should mention is the way we succeeded in winning certain battles. This is important from a psychological point of view. That is, in this job, we never had any time. There were strict time limits for everything: decisions, contracts and construction deadlines. We were still deciding the project, as yet undefined in certain sections, when the building site went into operation. And this lack of time was an enormous advantage because it kept us from going back on decisions too often. Approvals had to be. granted without delay. Decision after decision: it was a chain within which we could not easily be stopped, whether on a political, destructive or public opinion level. And we have had our share of, at times, unjustified attacks. A typical one, came from a group of French architects, Grand Prix de Rome, who formed an association by the name of “Le Geste Architectural”: these gentlemen sued us six times. They did not sue us directly as individuals, but the entire context. They filed a lawsuit against the jury, because Prouvé, who is the only interesting character operating in the field of construction in France, is not an architect. Here was the basis of their accusation: the jury is not valid because Mr. Jean Prouvé is not an architect. Then we were attacked by exceeding the projected site by 30 cm. This is kind of nonsense. Also, we are foreigners... The arguments have always been highly unjustified and yet there have been about six lawsuits filed by these gentlemen. Once they managed to block the site for 15 days, with 1.000 people involved. And you can imagine what that implies. Dynamite! Anyway, it was very lucky for us that we had such strict time limits, because all these things were swept away in the process.

C.C.: What did you succeed in doing, what were you unable to do?

R.P./R.R.: With regard to the environment, what we obtained with some difficulty, after the competition, was that the streets around the building, on the side of the "piazza" be pedestrianised. This will be the largest pedestrian zone in Paris: 4 to 5 hectares. The area which goes from rue de Rivoli to rue Rambuteau between the boulevard de Sébastopol and rue du Renard is already a pedestrian zone: the “pavage” is being re-done, trees are being planted, playgrounds are being built, and the outdoor fittings are being replaced. The Ville de Paris is implementing a project here in which we can all participate. The pedestrian zone was fundamental in a city like Paris with so many cars; it's obvious that the Centre Pompidou “landed” in this urban centre like a huge catalyst magnet, so it was necessary to create around it a physical space where there would be no traffic, noise or danger etc., that would be suitable to pedestrian activities or to leisure activities: the Centre needed, in other words, a surface of contact with the rest of the city.

This was one battle we won. Whereas, still on the level of the environment, we did not manage to obtain control over the functional activities around the Centre which we did not wish transformed into pseudo-cultural activities (little art galleries etc.). The public authorities, that is the Ville de Paris, did not support us in that direction (aside from a minimal amount of control in certain areas falling under the jurisdiction of the Centre): the flow of capital and the real estate racket were obviously too powerful. At any rate, especially at the moment, the French press is indicating that the Centre Pompidou has given new impetus to activities in the centre of Paris. As a matter of fact - aside from the negative phenomenon of old bistros being turned into art galleries - new things are beginning to happen in a rather spontaneous way: a circus will be installed in the piazza, which is something we had planned for, and there will be flower markets, which is something we had asked for. Already in the neighborhood, new bookstores, information centres and small theatres are making their appearance. The destruction of the Halles, which coincided with the beginning of construction on the Centre (creating a great deal of confusion, both in France and abroad, as many associated the demolition of the Halles with the construction of the Centre Pompidou, which are in fact unrelated: the Halles being on one side of the boulevard de Sébastopol, the Centre on the other) had generated a trend, whereby for a couple of years the abandoned space of the Halles had spontaneously been put to alternative unofficial uses: groups and teams went there to work, express themselves, hold meetings and theatre performances; these and other informal activities were taking place quite freely and openly. In a sense, all of that is now beginning to happen around the Centre. Not inside of it but around it.

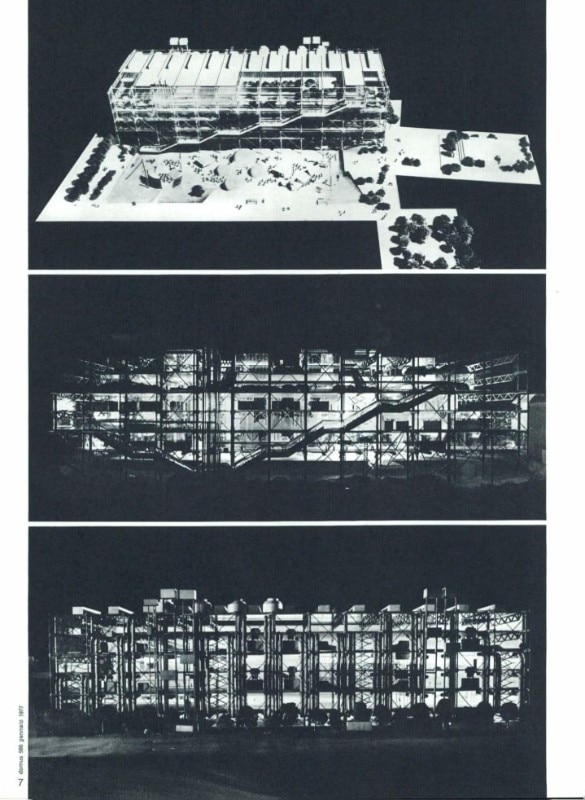

So much for the environment. As for the building, there are two essential distinctions with regard to the competition project (aside from the difference in height, from 60 to 42/45 metres, which we ourselves stipulated). The first distinction is on the level of volumes: in the project, the primary structure is a large grid only partially (60%) occupied by the constructed volume. That is, not all the spaces were full, and the constructed volume was cut up and fragmented. However, during the phases of «avant-projet sommair” and “avant-projet définitif”, that is during the executive planning stages, there was a sudden rush for space and volume typical of a certain sort of “manie de grandeur”. The concept of the Centre as catalyst of the crème de la crème of France was starting to take, and everyone wanted to be there, and everyone needed 200 extra square m. Gradually we were forced to give in, and now 85% of the space is occupied by volume. The grid is nearly full. We lost this battle: we might have been more firm and we might have done a better job of defending the quality rather than the quantity of space and the fact that a flexible space is much more useable than a non-flexible space. We didn't manage: now for instance, on the ground floor, 10 of the 13 bays are full, whereas initially, when there was no volume at all, and the piazza passed beneath the totally transparent building, the piazza could be seen from the back street and vice versa. Now people can no longer pass through the building and that is regrettable seeing that in Paris, covered spaces are extremely precious: all the parks. including the Luxembourg, have many small pagodas and other small covered spaces where people go to find shelter from the rain and humidity, to play chess or do a hundred other things. Even on the higher level, the building was much more broken up. The floors used to have several 14 m double heights which are no longer there. This excessive use of volume has resulted in a loss of lightness and functionality with respect to the initial design for the piazza.

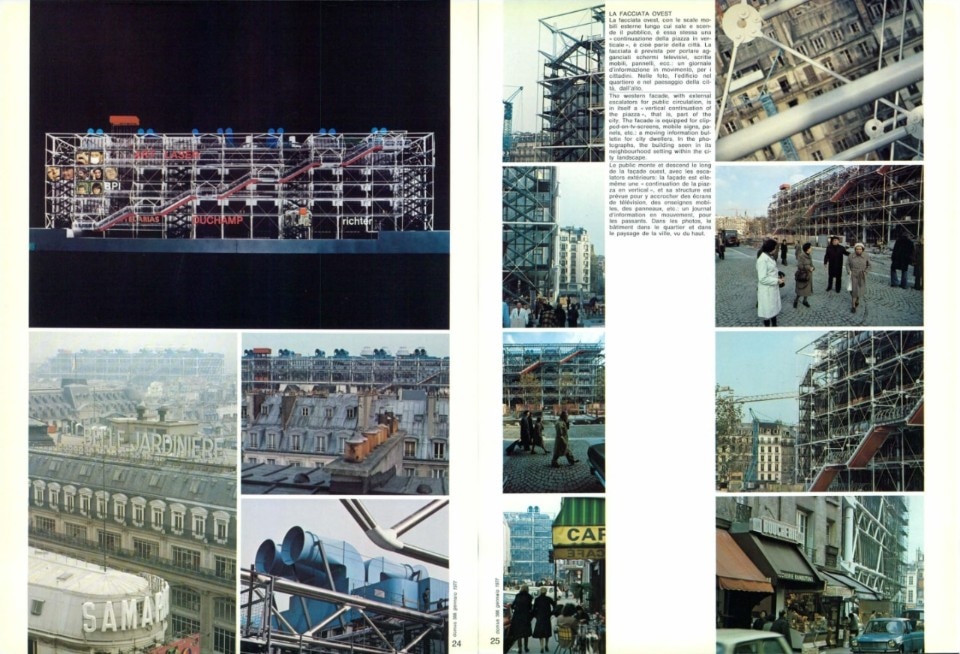

The second important distinction, with regard to the project, is in the use of the building as a “support of information». Here we encountered some difficulties from the outset. The building had been seen as a utensil, in the sense of its interior being used for diversified evolutive activities, while the exterior would constitute the contact surface of the utensil, or rather, its external articulation: a surface of screens, tv screens, movie screens, written messages, newsreels, etc., This was, actually, very difficult to achieve: not for technical reasons (as a matter of fact the building can at any time be used to that end, and we fully intend to do so: apparently, a large outdoor tv screen measuring 7X12 m will be installed), but for political reasons. Clearly, it's very interesting to talk about information, but it's hard to do so without someone immediately worrying about what type of information.

The Centre was becoming an information centre in the heart of Paris, a small, independent and autonomus ORTF, and it was evidently threatening to have an information center which could be occupied by students and put to highly effective use.

So it's not as though we lost on a projectual level. The building and its structure were made for this. There are actual external clip-on points (for screens, panels, moving messages etc.): for instance, the piece we call “sputnik”, at the intersection of the tension columns which is the clip-on point for these external elements and also for the escalator sections which can be disassembled and moved along the facade.

At any rate, these are the two basic differences with regard to the initial project for the building. I would say that we succeeded in doing everything else: we created a building which is a container-utensil, as we mentioned earlier: a utensil in terms of use and a container, for operations and actions as well as objects; a utensil within which, and with which, one can operate creatively in different fields, from art to research, in the field of construction, the environment and communication. A flexible and evolutive space. (It's a very beautiful idea: seen in physical terms, it becomes evident that to carry out this type of construction, with floors measuring 50 m by 170 m of free span and a 500 kg overcharge per square meter of flooring for reasons of flexibility, is no joke).

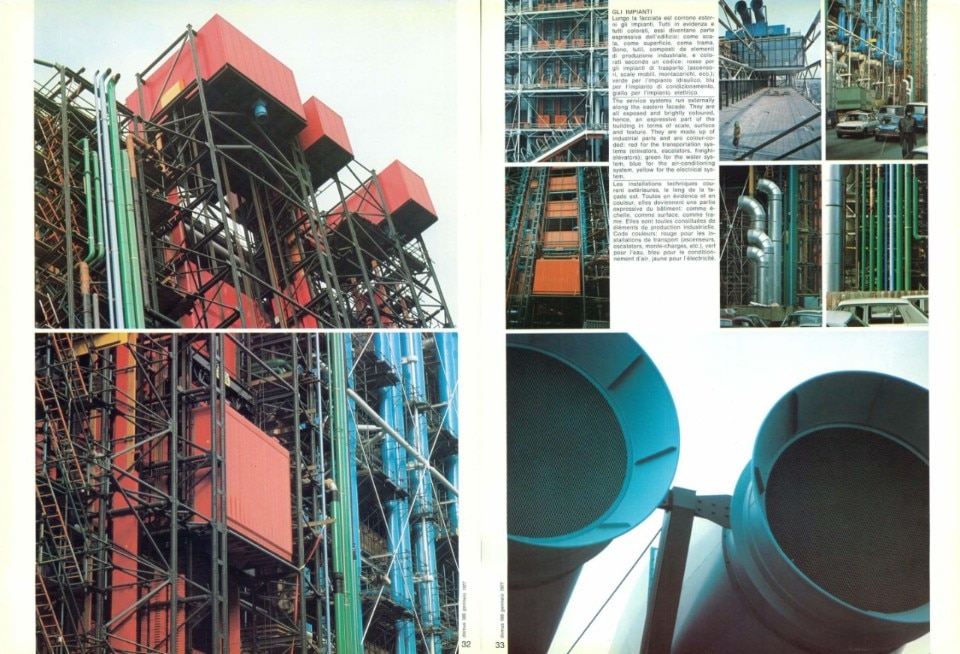

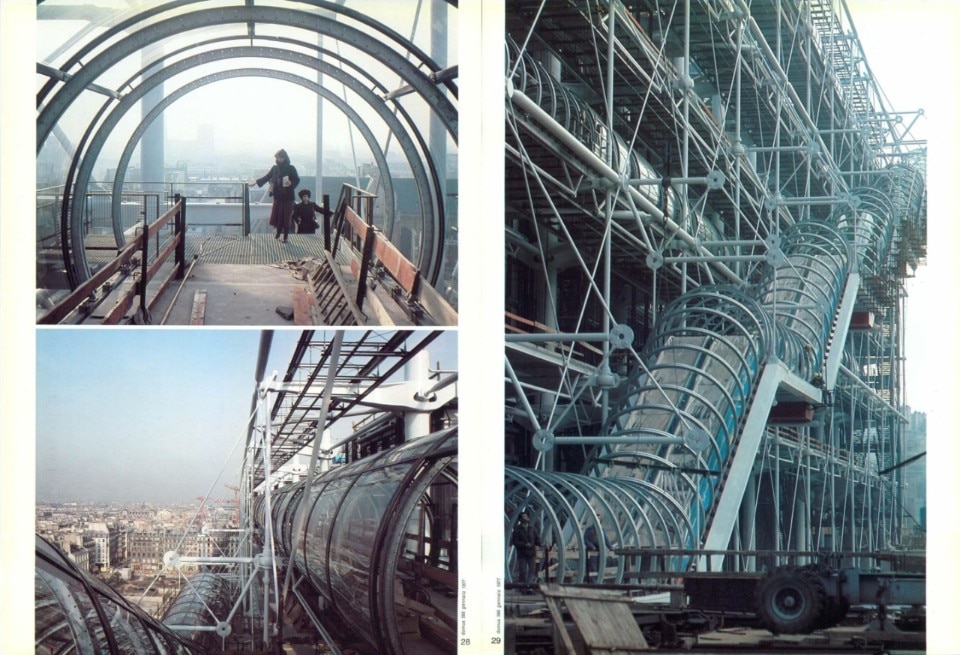

The building consists of 5 floors, each approximately 7 meters high - extremely large and totally empty spaces. In order to give an idea of scale, we always used to say that four football teams could play simultaneously on each floor: and that is in fact true, since there are no vertical obstacles. All of the building's fixed elements (such as stairs, escalators, mechanical services and columns) were “pushed” to the exterior so as to free the internal space completely. These elements are assembled in the various “systems” which make up the building: which are juxtaposed and integrated among themselves. There is the primary structure system, or supporting structure of the building, which created the support framework.

Then there is the tertiary structure system, or light structures, such as the fire escapes, the supporting elements of the galleries, all the elements “plugged into” the building. Then there is the mechanical service system, clipped onto the primary structure, which runs vertically on the exterior along the building's east facade, penetrating horizontally on every floor, along floors and ceilings (both of which are equipped, at every point, for hydraulic and electrical hook-ups). Finally. we have the extremely important system of public circulation which, again, is physically clipped onto the outside of the primary structure; it consists of the diagonal escalators, the transparent external galleries, the elevators along the western facade of the building. which can be seen from the piazza. All of these external systems are relatively independent.

The mechanical systems are separate and can be expanded or reduced, as can be the system of public circulation. With regard to the public, the building was designed to contain up to 5.000 visitors at the same time. An entire village population: the circulation system could not be designed as a “digestive tube” system: it is an intelligent system, which allows people to circulate knowing where they are going, experiencing the adventure of the building they are visiting. seeing the piazza and the interior: it's an extremely important system.

Opening image: Photo Denys Nevozhai from Unsplash