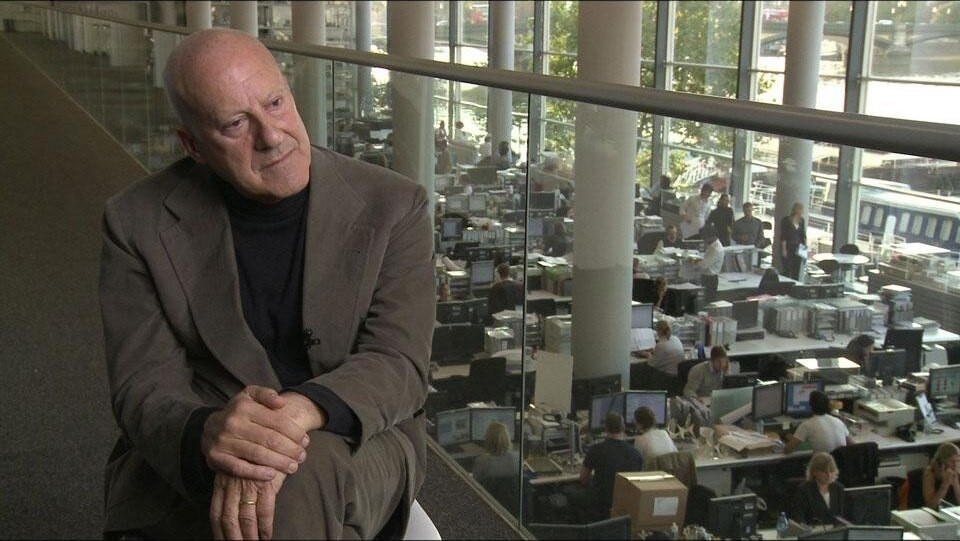

A dog kennel, the Hong Kong airport, solar panel landscapes and underground transport experiments in the United Arab Emirates. All these projects participate with equal importance and media prominence in the galaxy of language associated with Norman Foster. A designer at large, not only designing architectures or products, who has recently started to keep a distance from the High Tech label: “I don’t think my designs are high tech. I think that we were interested in the performance of buildings, yes. But probably, the highest technology buildings you could think of are, probably, cathedrals...” he told Domus in 1998 (Intervista a Norman Foster. Domus 806).

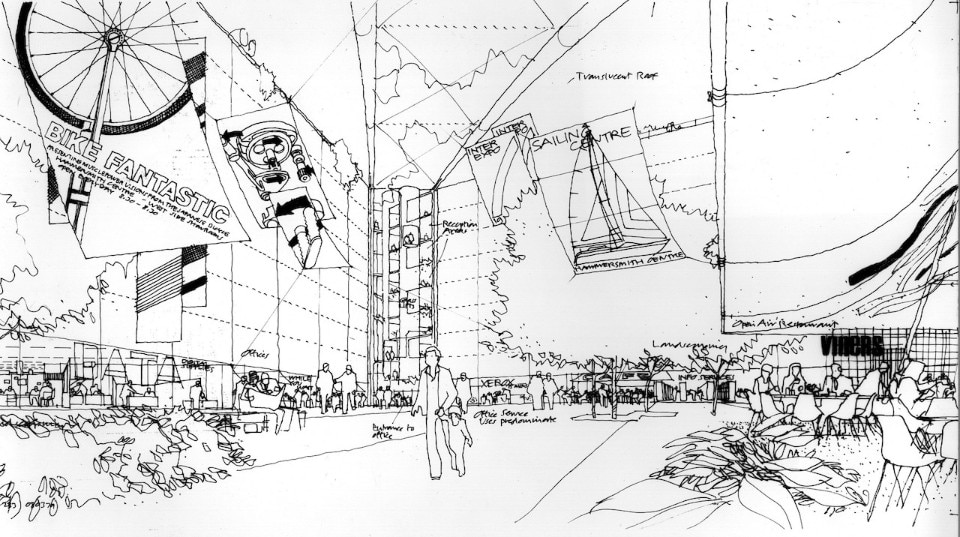

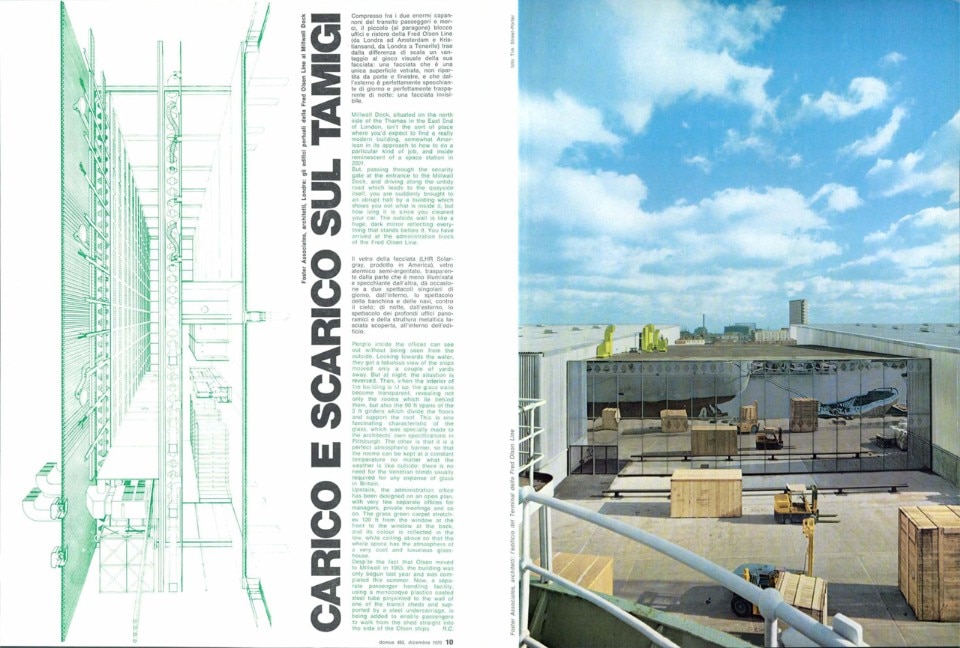

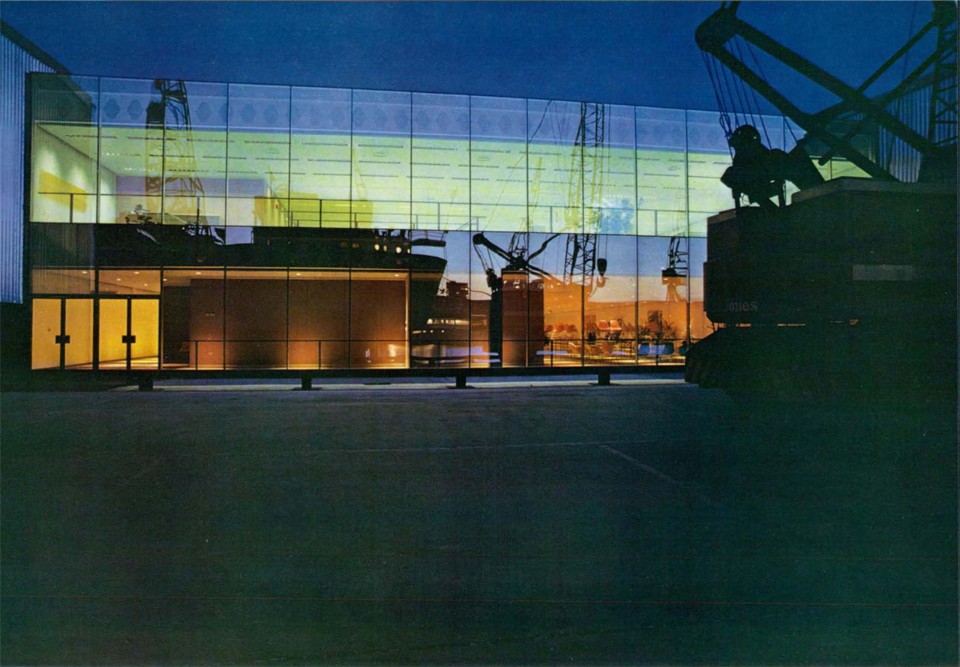

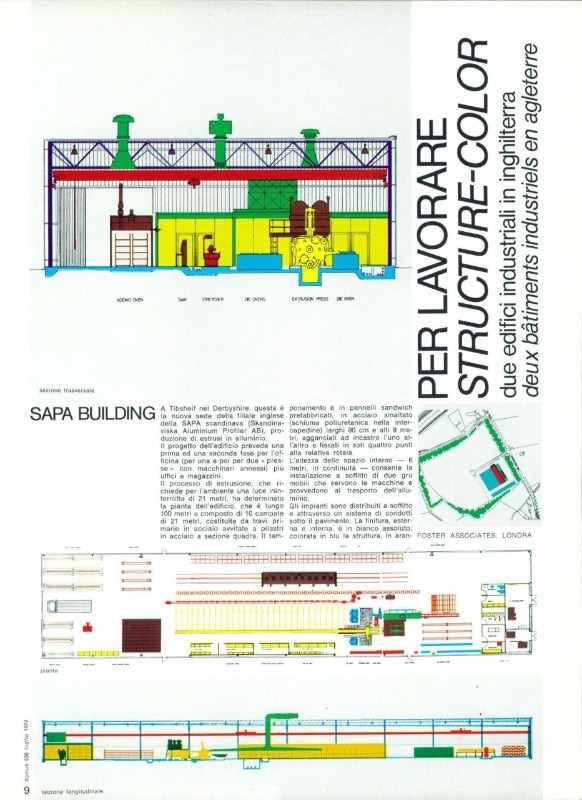

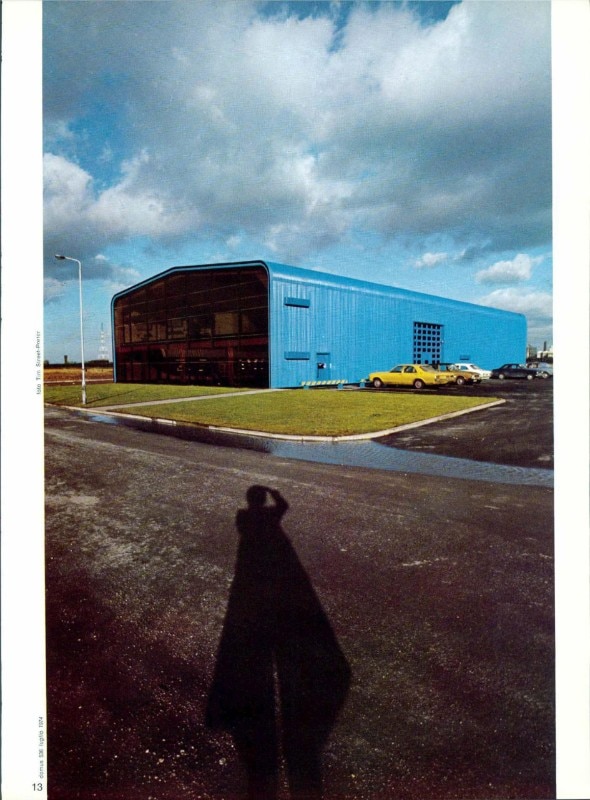

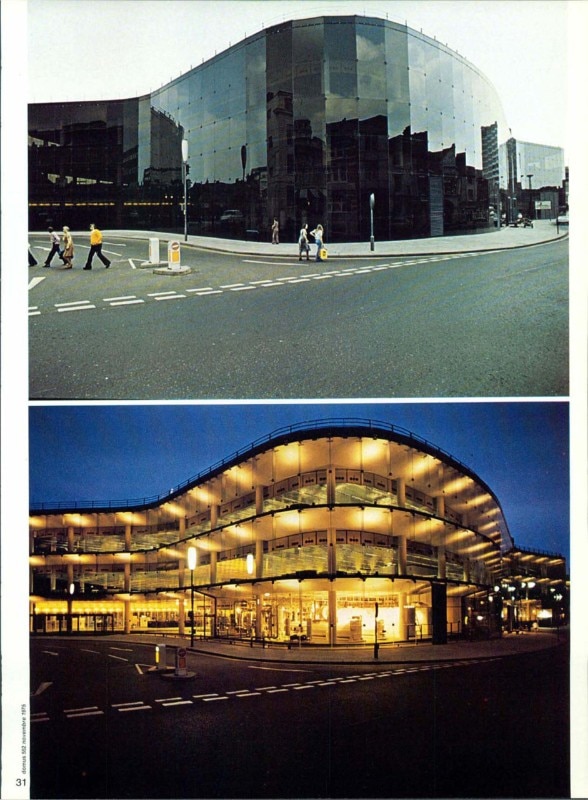

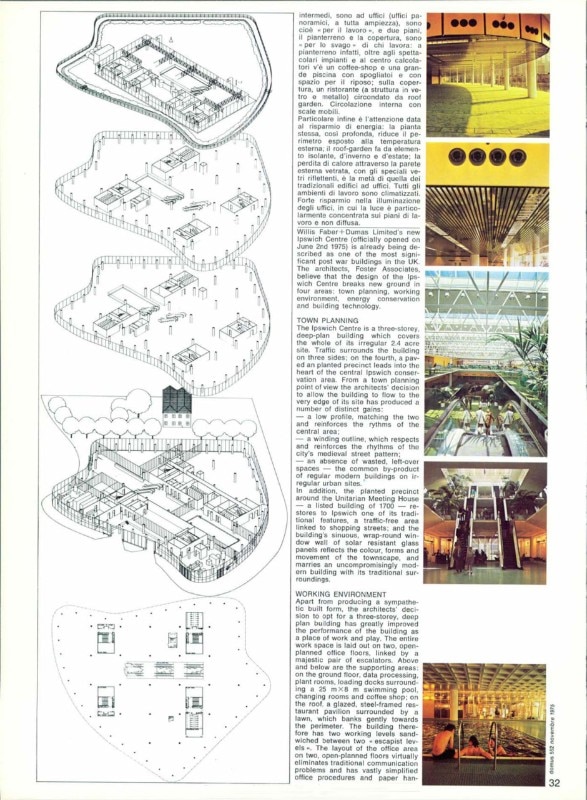

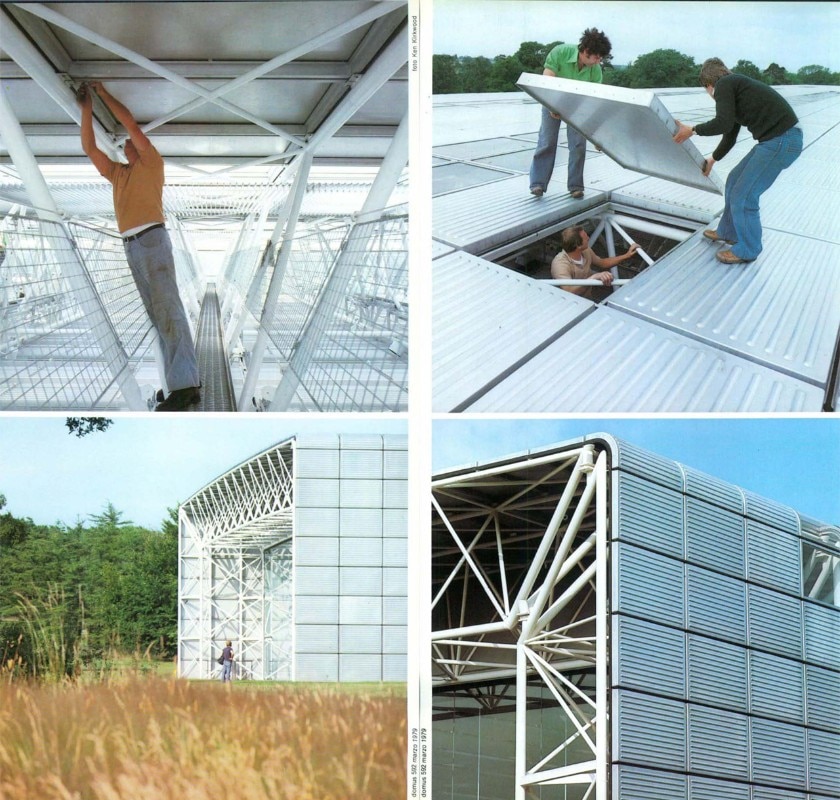

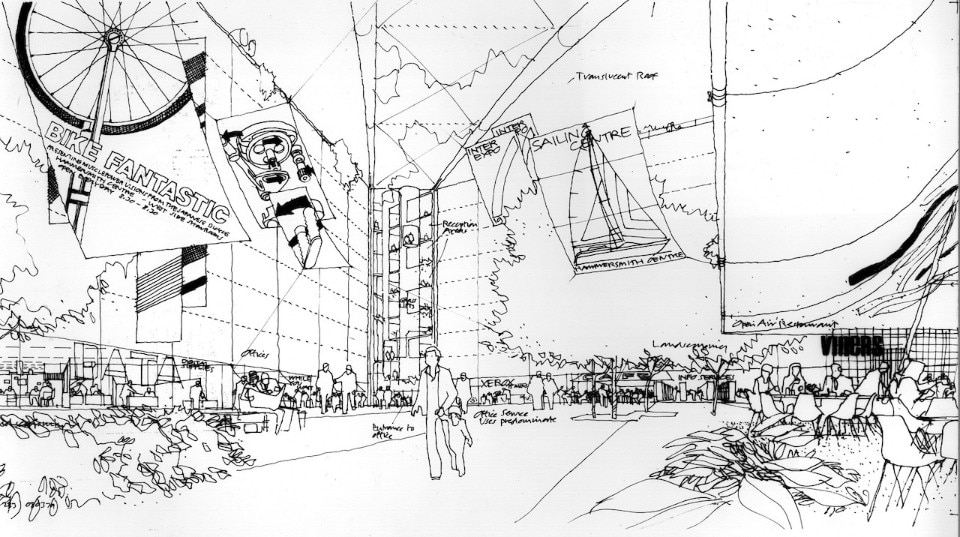

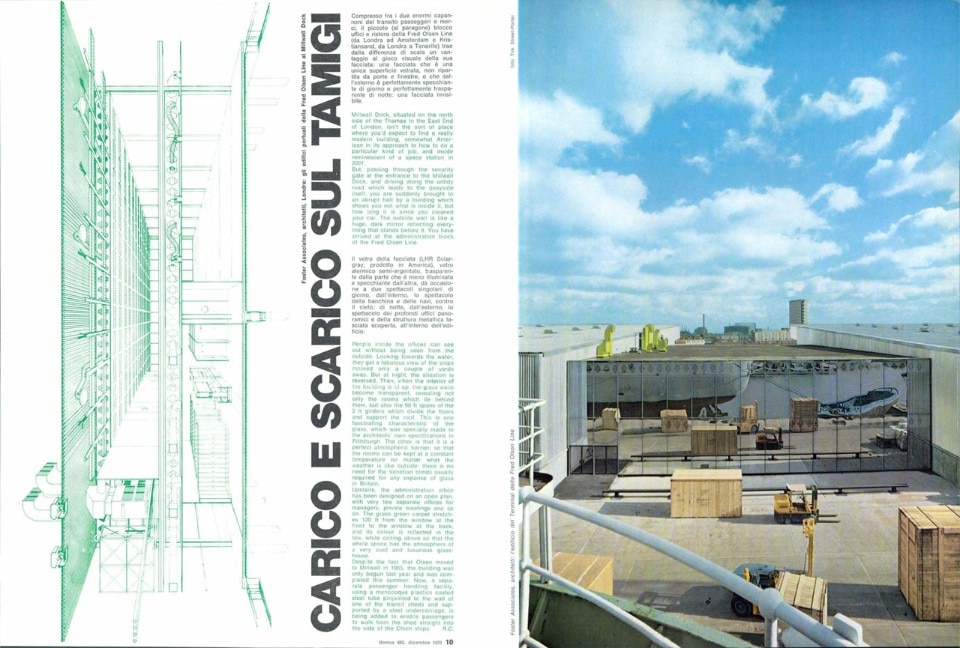

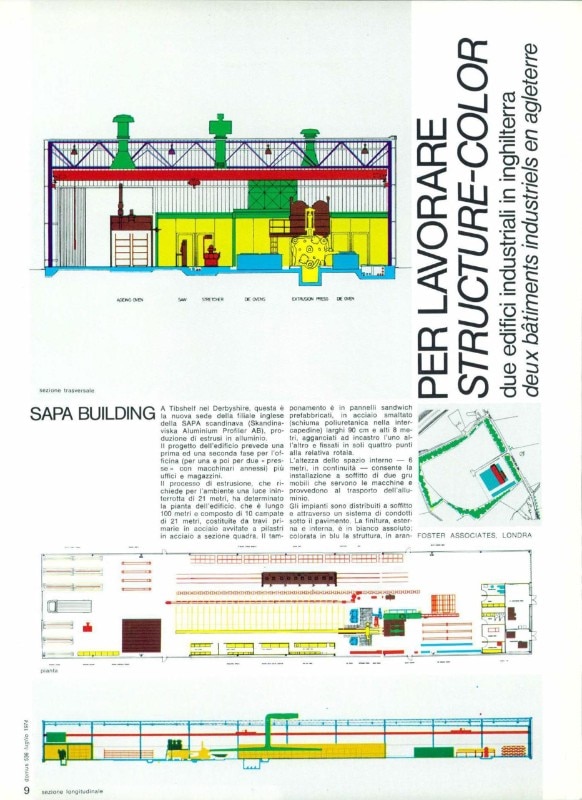

Still, on the pages of the 70s Domus, a real landscape of hi-tech was built through Foster’s projects, which seemed to exist to confirm those radical dreams that architects were dreaming at the time: the Willis Faber and Dumas in Ipswich (New in England. Domus 552, November 1975) the SAPA building and the MAG building (Per lavorare. Domus 536, July 1974), the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts (Per l’arte all’Università di East Anglia. Domus 592, March 1979), all of which are now recognised as masterpieces. There was also room for that lesser-known project which was, however, the first to be published, and which combined all the elements that created the poetics of a whole movement and a decade: the dock complex on the Thames at Millwall Dock (Carico e scarico sul Tamigi. Domus 493, December 1970) is a hybrid machine, mysterious by day behind mirrored glass, alive at night with all its mechanisms in exposed action, its interiors so similar to radical scale models à la No-stop City.

But the 1970s were also the years in which the context of criticism was violently swerving towards the postmodernist realm: the radical would merge into it in a certain way, and the same was to happen to the interpretation of High Tech itself, which arrived in the 80s already transfigured and relativized: “While architecture as image or identity would horrify Britons, smelling of too much ‘commercialism’, High-Tech architecture can be pure image because it masquerades as something practical. The High-Tech architects, who dominate because of quality and influence, postulate a clean, ordered society; Clockwork Orange or Buckminster Fuller, depending on your point of view”. (L’umile e l’utile. Domus 637, March 1983. The villa where some Clockwork Orange scenes were shot was designed by Foster)

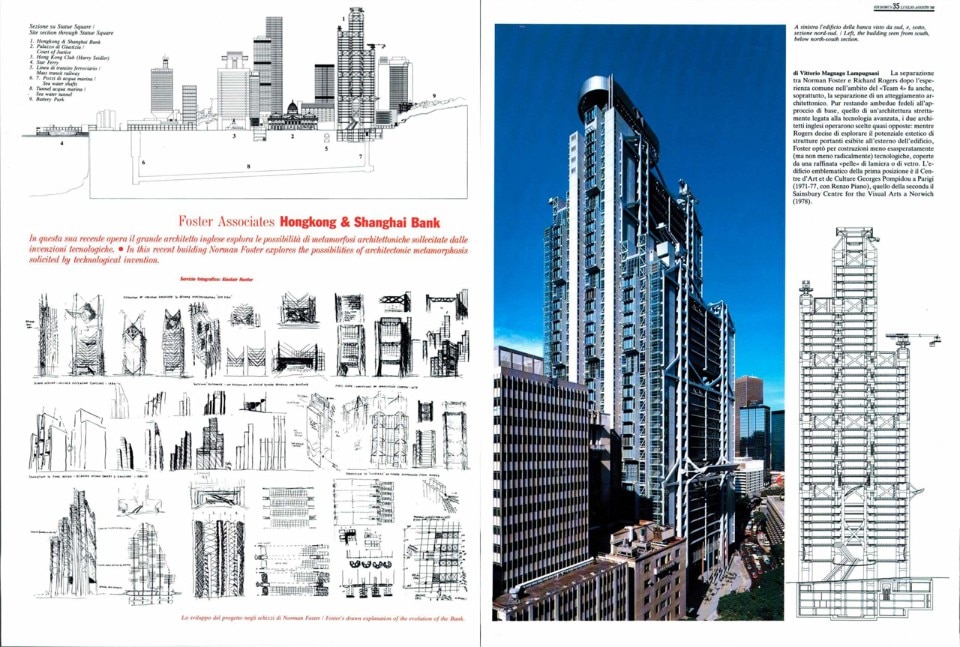

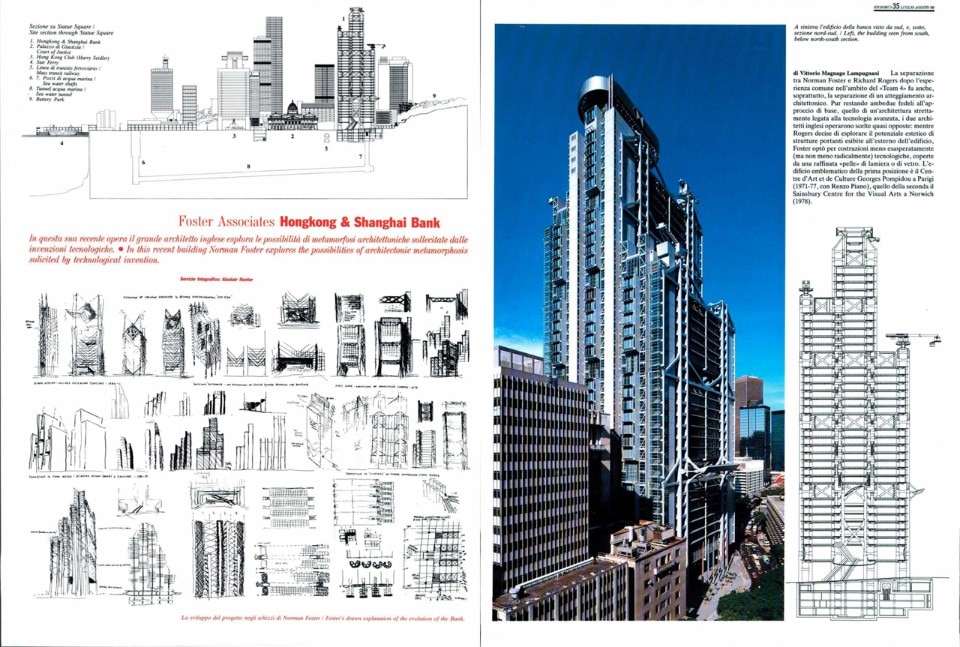

The following years then became fundamental years of positioning for Foster, embodying the very e evolution of High Tech. Unlike Renzo Piano, who broadened the geographies of his commissions but concentrated on maintaining a “craft” dimension to his practice, Foster with his Foster & Associates escalated to the level of a design company, the same scale of the large firms that had “built” the Modern throughout the United States and were on their way to becoming world-scale players. Foster’s big firm is positioned in an increasingly market-driven global economy, and this expresses in two aspects that the projects appearing on Domus tell us about: first of all, the affirmation of large private entities in urban transformation, as in the project for the King’s Cross area in London, a consultation won by Foster (“…the emergence of an ecletic and pragmatic architecture, with notable exceptions, that satisfies both the current conservationist climate and the financial viability of the enterprise”, writes Richard Burdett Domus 700, December 1988); second, a new season where this entities want to connect their image to powerful built symbols, such as the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank tower (Domus 674, July 1986)

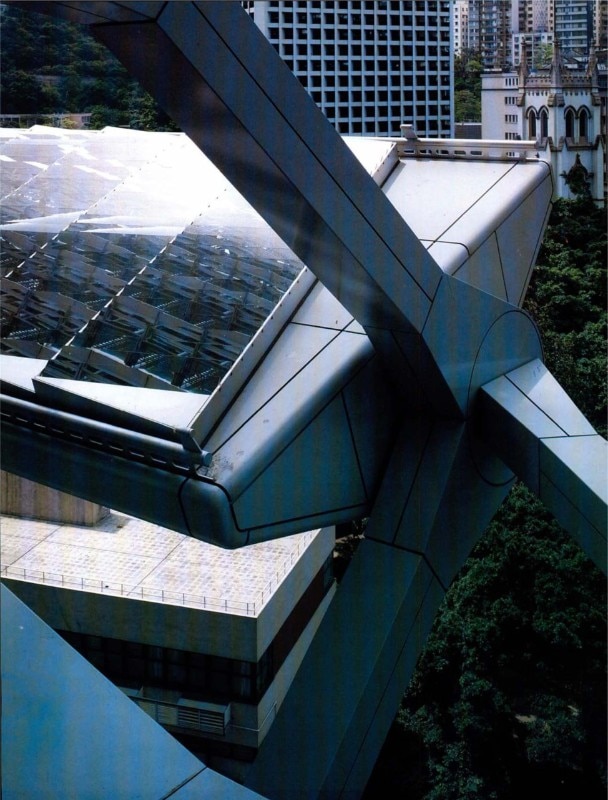

It is an instant icon, it opens the High Tech chapter in most architecture textbooks; its interior layout embodies the vanguard of its era, the theology of the open office with a large central void, and by exhibtiting its cyclopean trusses and the maintenance cranes on the rooftop, it escorts the language of machine aesthetics into its adult age.

“The Hong Kong Bank – its social organisation of village-like clusters of space, one above the other – began by challenging the typical high-rise structure that can be seen in every city.” Foster would say a few years later (Domus 840, September 2001) .

I can’t really draw any distinction between architecture and the scale of the small things that you come in contact with, whether that’s the doorknob or the lighting, the furniture, it’s all architecture.

Norman Foster, 1998

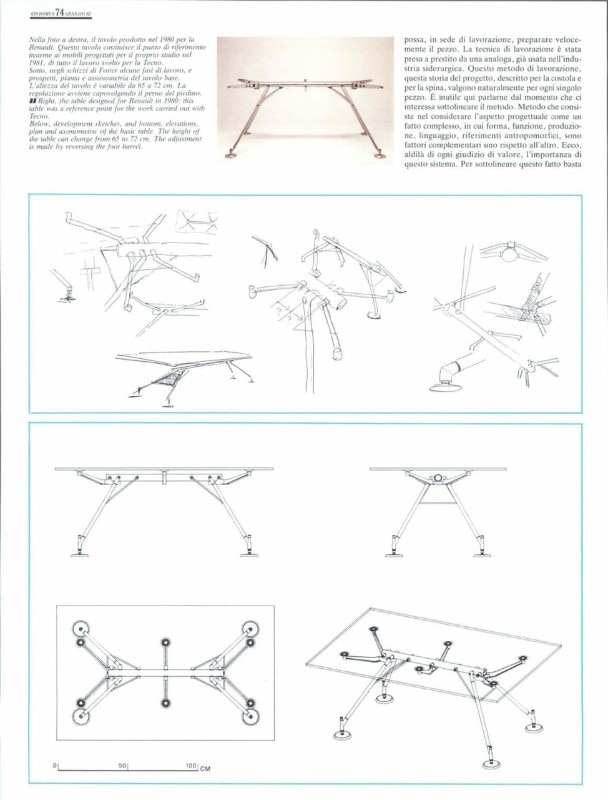

In 1987, a confirmation to such approach came from the realm of objects: the Nomos table is narrated (Domus 679, January1987) according to that same system-of-details syntax, a “technological” yet aesthetic object that would be able to fit into different contexts, up to the present day, establishing an intelligent dialogue in every situation.

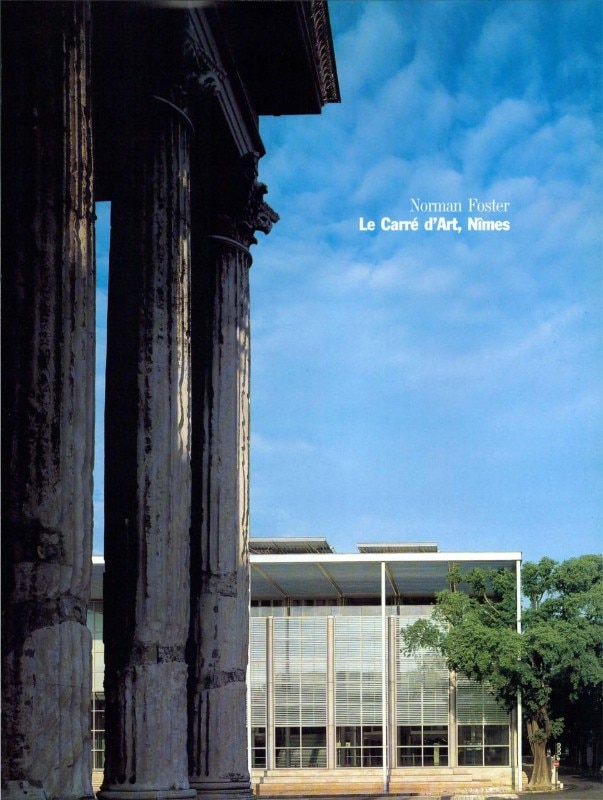

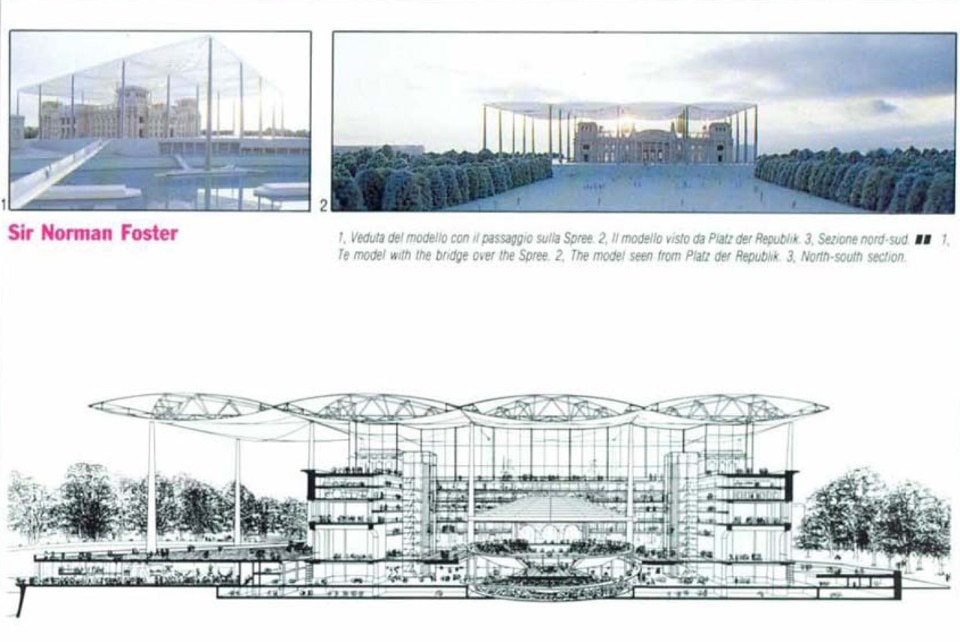

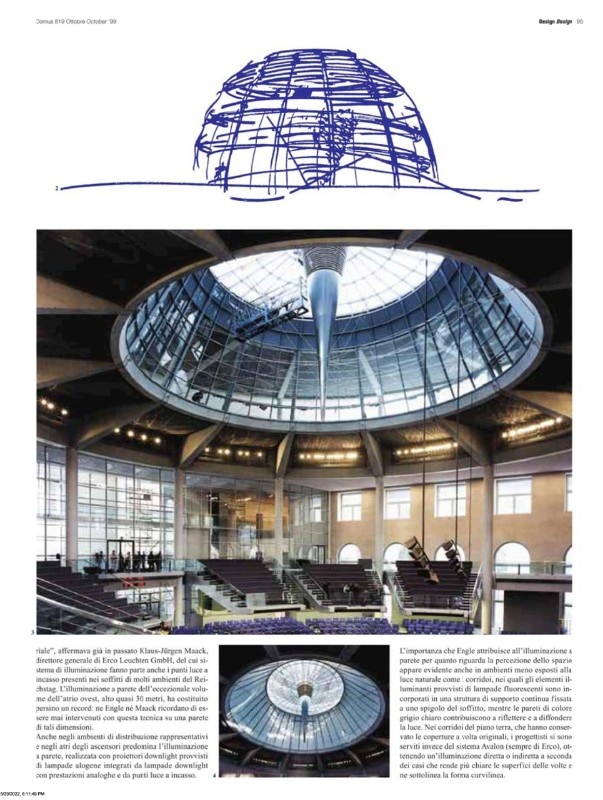

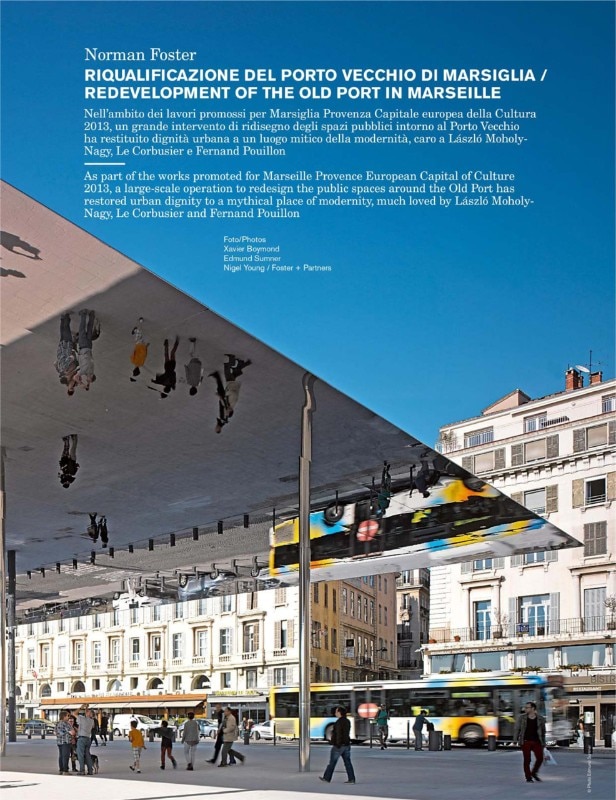

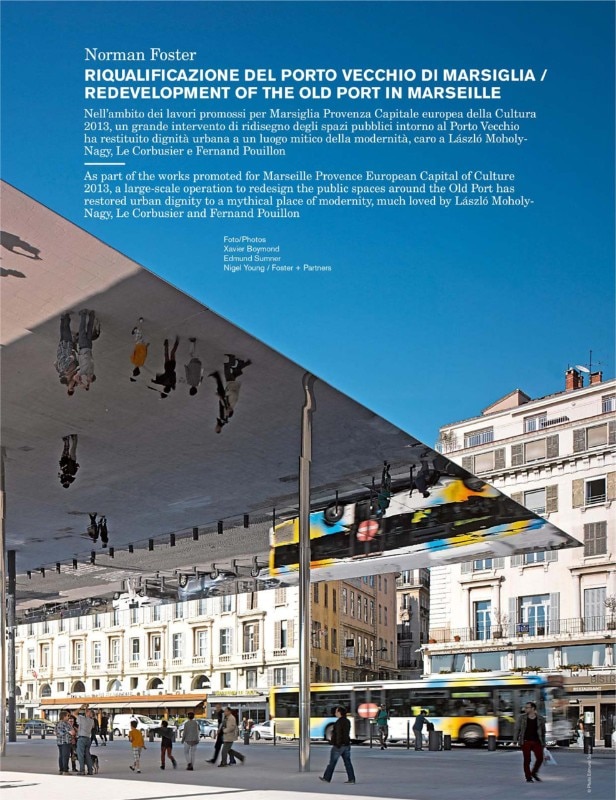

Technology, and its image, as a guarantee of successful mediation in complex situations, between contemporary solutions and historical context, between progress and memory, between outstanding episodes and consolidated city, wherever this mediation may take place. This is the position that would grant Foster some of his most iconic project opportunities, which Domus has published since the 1990s: the Carré d'Arts in Nîmes (Domus 751, July 1991), the Reichstag in Berlin – a competition for a restoration that he won by immediately exploring the path of dialogue, mediated by light, between an ex novo technical solution and the preservation of the existing place (Domus 748, April 1993 and 819, October 1999) – up to the 2013 plan for the Vieux Port in Marseille (Domus 973, October 2013), where the Grande Ombrière, a large seaside roof with reflecting surface at the bottom, represents the highest degree of essentialization and explicit effectiveness of his approach.

“‘I am no longer exactly sure what kind of an architect I am’, he said finally. This loss of his bearings hardly comes as a surprise. The buildings by the Manchester-born architect seem almost ubiquitous in key cities of Europe and Asia, thus acclaiming the truly global fame of their erector”, Patrick Barton would in fact write in 2000, quoting Foster (Multimedia Center, Amburgo. Domus 827, June 2000).

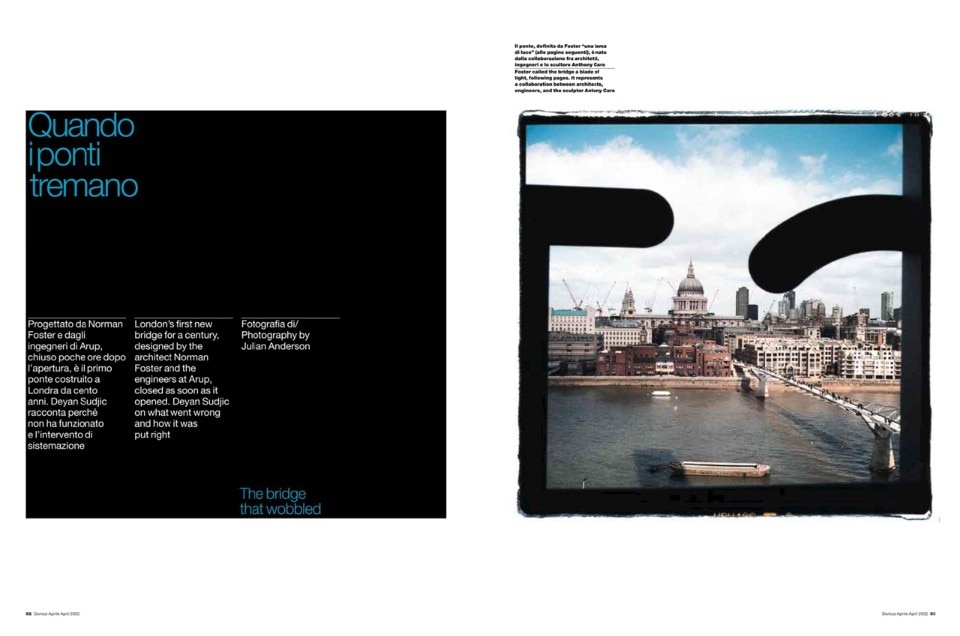

It must be said, however, that still in these decades it was not yet the author talking directly to Domus, but rather his project reports, or the reviews by his critics, both of which were very frequent, as well as the presence in reviews of exhibitions or new objects. It is actually a mode that would continue even after his first interviews, in parallel with his personal takes on his activity and the global condition. The Ripensamenti and Monitor columns with which Deyan Sudjic, in his years as director of Domus, follows Foster’s new season building the landscape of the capitals of the Third Millennium, London in particular, can clearly represent such mode. The work on the British Museum court, first of all, “a magnificent glass pillow shaped roof, that seems to recall the work that Foster once did with Buckminster Fuller” (British Museum: la corte di Foster. Domus 833, January 2001). Then the Millennium Bridge, opened and immediately closed to dispel that risk of harmonic oscillation whose terrifying first manifestation and the following choral resolution were vividly recounted (Quando i ponti tremano. Domus 847, April 2002) .

Then, the City Hall, and the reasons of its shape: “…compared to a motorcycle helmet and, by Livingstone himself, to a glass testicle (…) Foster talks about energy-saving to explain the shape, but fundamentally City Hall looks the way it does because of its struggle to make the essentially dull process of municipal government look more interesting than it really is”. (La casa del sindaco. Domus 852, ottobre 2002) .

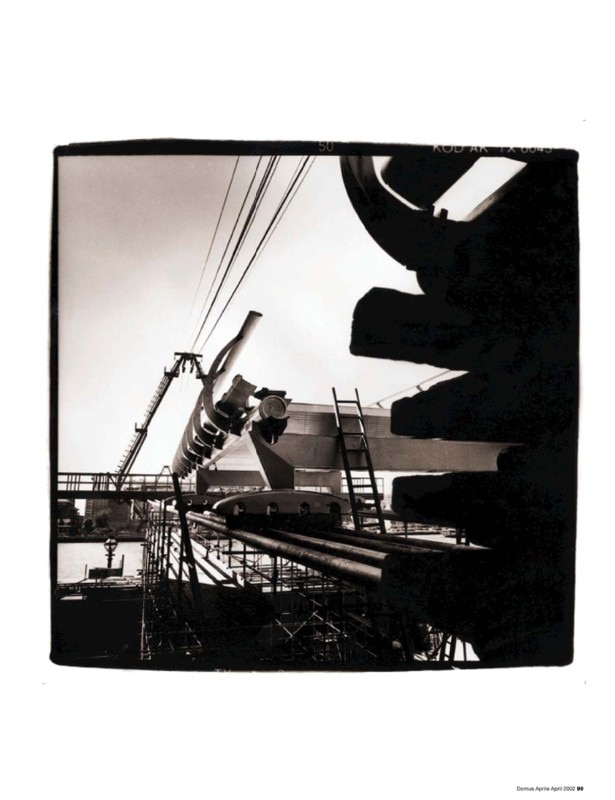

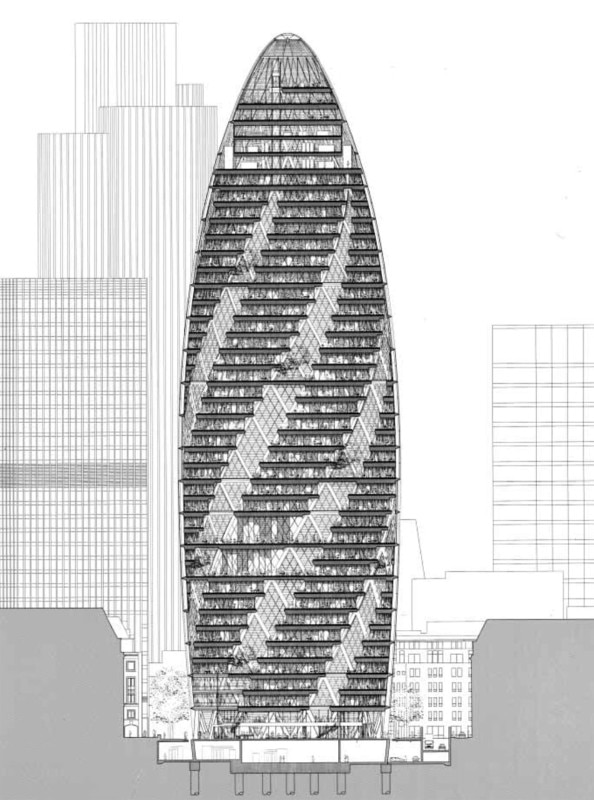

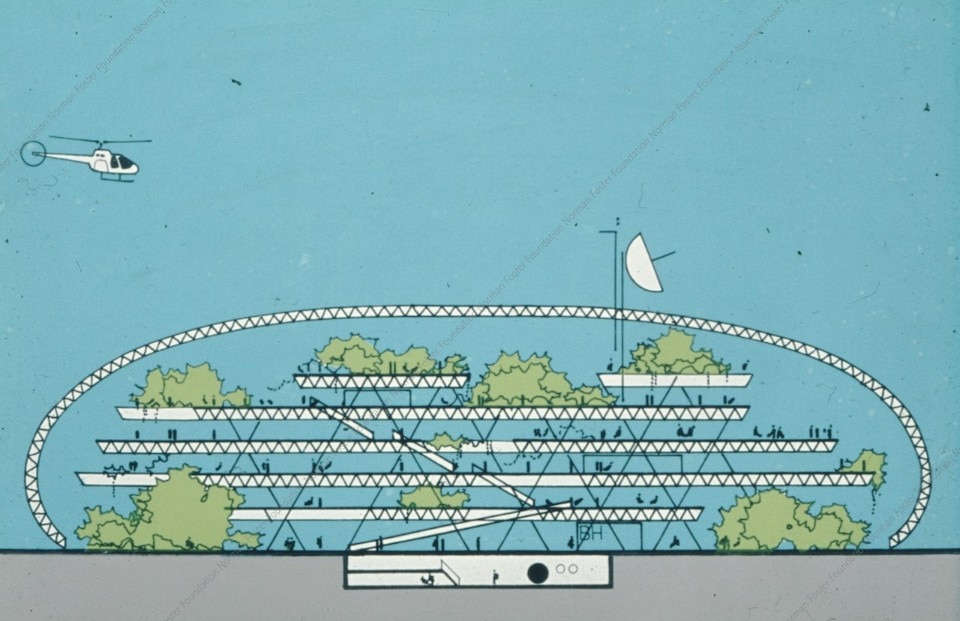

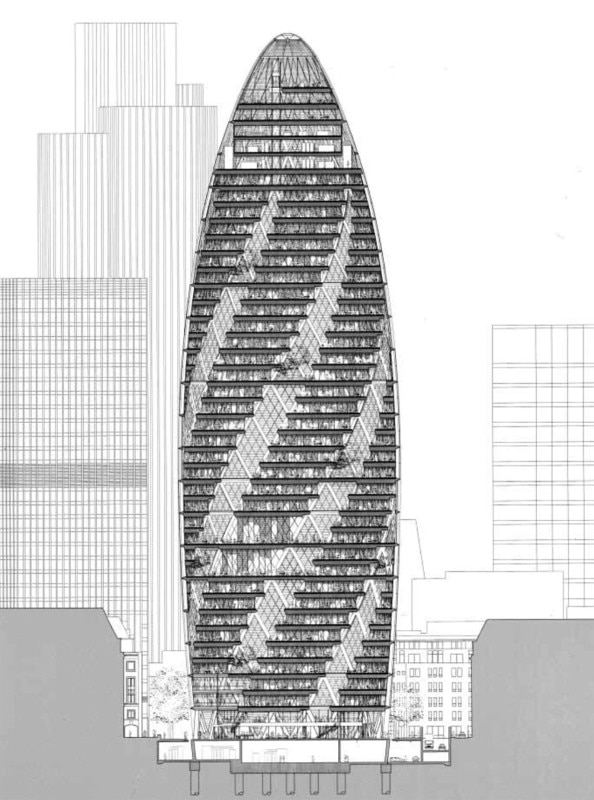

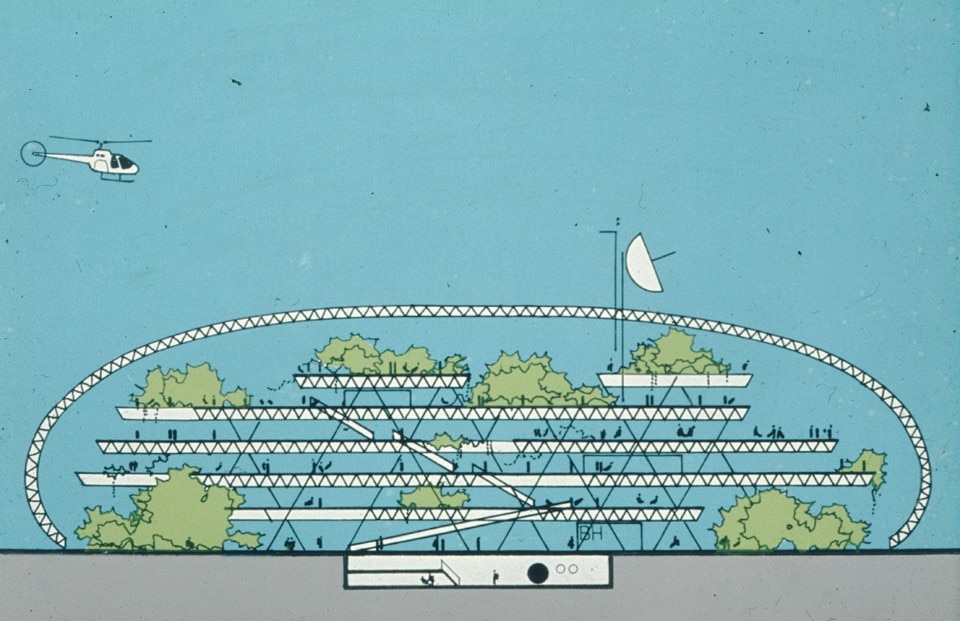

The Swiss RE tower, the Gherkin, was finally the one to be introduced by the words of Foster himself, in 2001: “…it consolidates and extends the innovations of the Hong Kong Bank and Commerzbank towers to create a socially and ecologically responsible building (…) Conceptually, the project develops ideas first explored in a theoretical project developed with Buckminster Fuller in the early 1970s. The Climatroffice suggested a new rapport between nature and workspace; its garden setting created a microclimate within an energy conscious enclosure, while its walls and roof were dissolved into a continuous triangulated skin”. (Il grattacielo ‘responsabile’. Domus 840, September 2001) .

The science fiction of my youth is the reality of today. The science fiction of today will be reality for the next generation. The pioneering cities of the future are set to similarly amaze us all.

Norman Foster, 2019

Foster’s role as a reference figure, shaping visions from the position that decades of projects have secured for him, is the hallmark of his recent years, a figure of research embodied by his Norman Foster Foundation in Madrid (Domus 1010, October 2017) and by his frequent tendency to putting into perspective the multiple architectural and urban visions that have come down through history, thus stressing their value for the future, even with no mercy for projects of his own: “Taking a building that we created some time back, the “Gherkin” in the City of London and projecting into the future, I can imagine that it may no longer exist as an office building as they will have become obsolete; perhaps it will be a vertical farm producing actual gherkins with a farmer moving them around by drone!” (Qual era il futuro. Domus 1040, November 2019)