“Setting out from the utopia of an endless grid based form, Renzo Piano reasserts the ethics of hand made things. Aldo Loris Rossi reinterprets the technological challenge of this utopia: its limits and its perspectives".

Some crossovers could sound almost impossible today, but it is in fact a matter of mythologies that over the years crystallized around some characters, leaving only their surface to shine through. Aldo Loris Rossi and Renzo Piano today may seem to come from different planets. Rossi, who would have turned 90 in May 2023, is today hailed as probably the best-known exponent of brutalism in Italy, now freed from the burden of an unwieldy namesake, but tied in a double knot to the image of his Casa del Portuale in Naples (Domus has dedicated a cover story to it in March 2022, issue 1066). Piano, in 1983 when this encounter happened, was already a representative of High Tech and strong design ethics that would build his myth in the following decades.

It happened that, on Domus, Aldo Loris Rossi would one of Piano's projects, the hypothesis of a new integration for the Milan fairgrounds, as much to explore in depth the “new” attitude of the Genoese designer as to profile architecture in an era, through critical categories such as those through which that era had been outlined, even shaped, by Reyner Banham. The essay – titled The well-tempered environment not by chance – was published in April 1983, on issue 638.

The well tempered environment

International Style, which had by then been reduced to the one-dimensionality of industrial processes. The new horizon reached past the informal avant-gardes, which had become self-confined within their unindustrial operative modes; and past the neo-realistic movements still clinging to the paleo-industrial myths. The ideology of the Modern Movement itself having been questioned, what were the prospects for the generation born in the ‘30s – to whom Renzo Piano belongs – who were then appearing on the scene of the debate? What consequences were implied by the break in the form-function-structure continuum which had been one of the Modern Movement’s cornerstones?

In actual fact, contrasting conclusions were drawn from the discontinuity found in this chain of relations. For whilst interest was concentrated on form, seen as independent from function and structure, a rediscovery was made: of the façade as a mask indifferent to the building’s inner reality; of decoration as an autonomous value; of institutionalized stylistic elements such as columns, windows, tympana, shrines, cryptoporticoes etc... In other words, there was a rediscovery of anti-(post)-modernist tendencies as integral formalism: an implosive reaction played on the modules of a renewed artistic approach. Conversely, if interest is focused not on the epidermis but on the structural skeleton, rendering it independent of function and form, then unexplored horizons are opened up. True, the Principle of Form is destroyed, but it is replaced by a structure as a field, open to multi-use and to linguistic pluralism (and hence to user participation). That is to say, the notion of neoavantgarde takes the form of a radical anti-formalism: an explosive widening of development towards the phenomena of de-artisticization.

Renzo Piano belongs to this second operative area. He sharply rejects all restoration. He is substantially adverse both to the whited sepulchres of the “Tendenza” and to that of being cast ashore in a post-modernist dreamland. In Beaubourg he knows that “mimicking the classical and attempting an approach by similitude” degrades architecture to a hollow exercise in rhetoric. He says: “I confirm that I am very hostile to the revival of the classical through its stereotypes, arches and columns. Indeed I think this is not at all a genuine, but rather a false way of reviving it”. As an intransigent antiformalist, he distrusts pure linguistic alchemies and wants no truck with any kind of mannerist experimentalism. His incessant preoccupation is to get back to the origins of architecture, to the original moment in which, to adhere to a purpose, the forces of matter are first structured as formal energy and thus as geometry. The Kunstwollen is identified with the intentionality of matter in “formation”. From his familiarity with constructing and from the teachings of such masters as Albini, Kahn and Makowski, he attains an ethic “of doing things with my hands” as Techné, which is at once cause and effect of the formative process adopted. A method based upon a twofold movement that leads from creation in the mind to realisation and vice versa, from the theoretic and mathematical phase to the physico-experimental one and vice versa, from the particular to the general and vice versa, etc., in a continuous circularity where “essentiality means using materials to the best of their condition”.

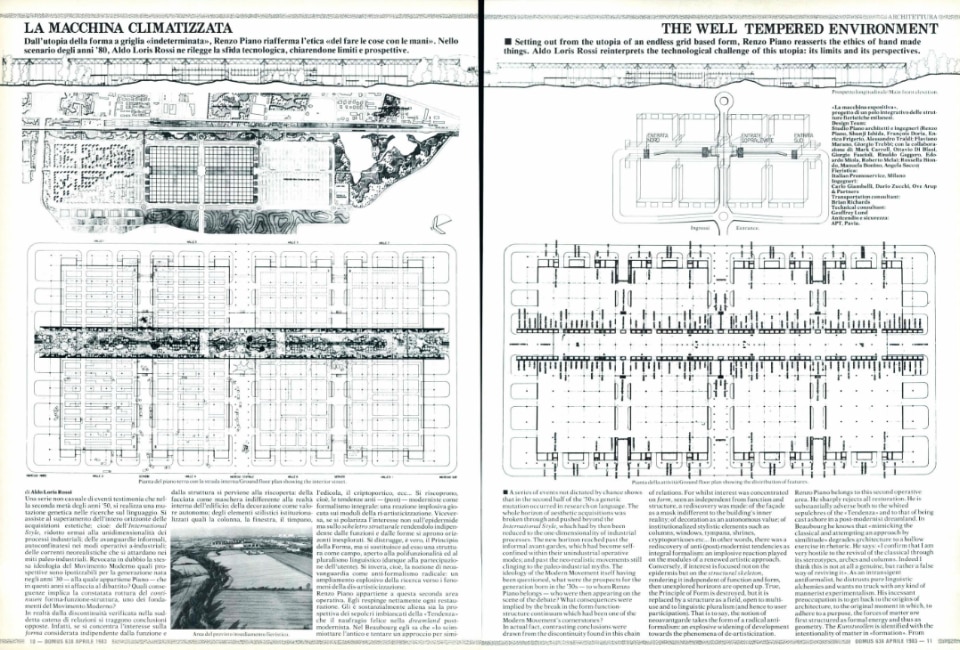

But Piano derives the richest implied consequences from the break with the Principle of Form, proclaimed by the neoavantgardes. If Form as a transcendental synthesis of values is a utopia and “the architect’s profession, owing to the way it is practised ... has permanently declined,” it is necessary to forgo giving form to spaces and to restore to users the right to creativity. The architect’s rôle as guardian of formal values must be transformed into that of a technologist of spatial structures which are equipped and flexible, not finished, and substantially formless. They must be place-supports translatable into space lived in by inhabitants. The utopia of Form, in conclusion, is broken on the one hand, into the construction of “indeterminate” structural grids and, on the other, into the ideology of participation. This explains the apparent paradox of Piano who, though working “piece by piece” on the most rigorous spatial modules, at the same fights for the involvement of users: from the Centre Pompidou to the open plan homes, from Houston Museum to the Maintenance Laboratory at Japigia, from the Fiat VSS Prototype to the project for the Isle of Burano, to the project for the Milan Trade Fair, etc...

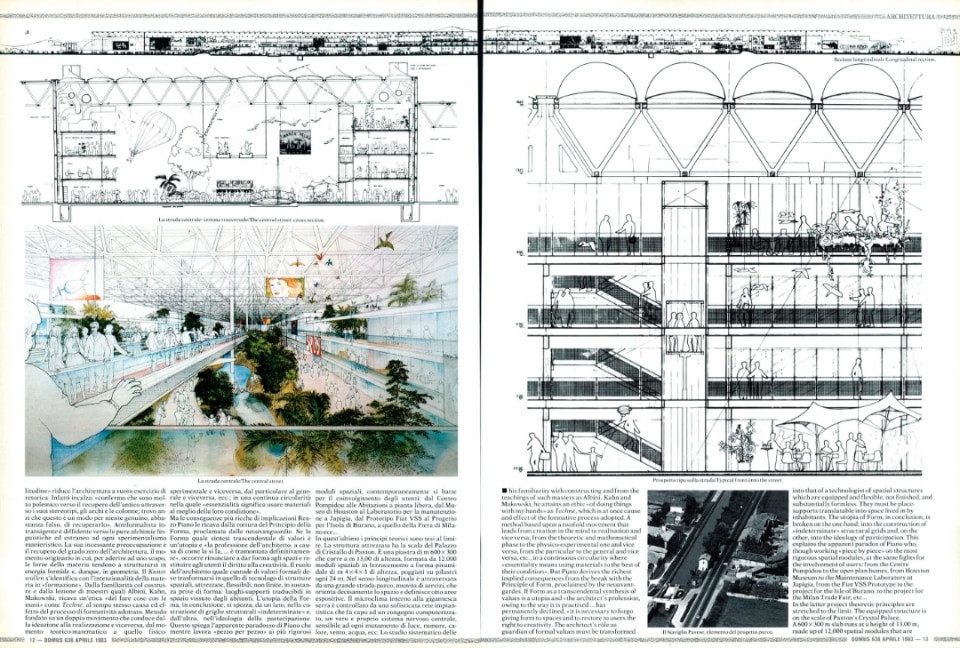

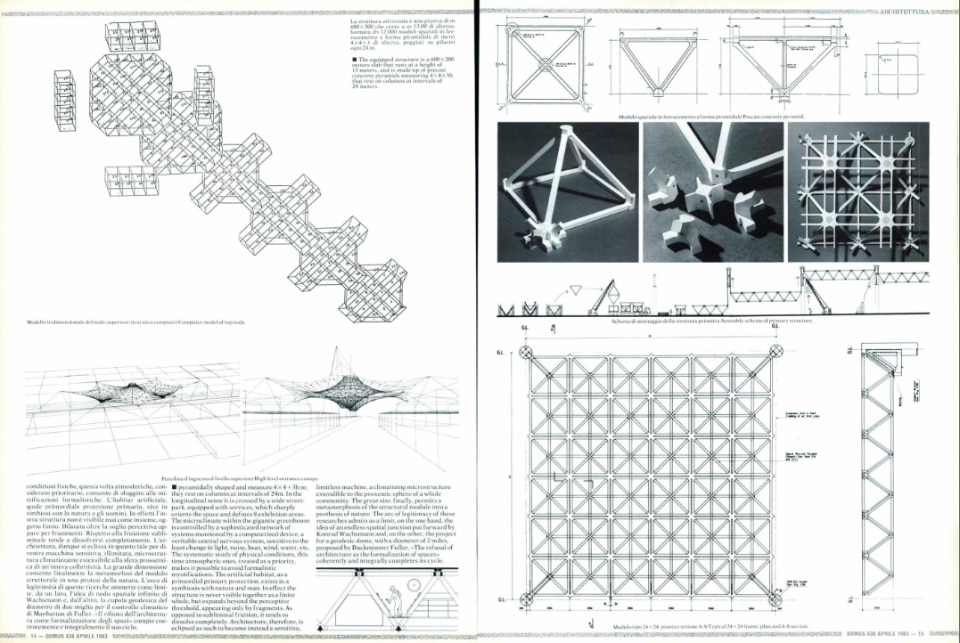

In the latter project theoretic principles are stretched to the limit. The equipped structure is on the scale of Paxton’s Crystal Palace. A 600 X 300 m slab runs at a height of 13.00 m, made up of 12,000 spatial modules that are pyramidally shaped and measure 4 X 4 + 3h m; they rest on columns at intervals of 24m. In the longitudinal sense it is crossed by a wide street-park, equipped with services, which sharply orients the space and defines 8 exhibition areas. The microclimate within the gigantic greenhouse is controlled by a sophisticated network of systems monitored by a computerized device, a veritable central nervous system, sensitive to the least change in light, noise, heat, wind, water, etc. The systematic study of physical conditions, this time atmospheric ones, treated as a priority, makes it possible to avoid formalistic mystifications. The artificial habitat, as a primordial primary protection, exists in a symbiosis with nature and man. In effect the structure is never visible together as a finite whole, but expands beyond the perceptive threshold, appearing only by fragments. As opposed to subliminal fruition, it tends to dissolve completely. Architecture, therefore, is eclipsed as such to become instead a sensitive, limitless machine, a climatizing microstructure extendible to the proxemic sphere of a whole community. The great size, finally, permits a metamorphosis of the structural module into a prothesis of nature. The arc of legitimacy of these researches admits as a limit, on the one hand, the idea of an endless spatial junction put forward by Konrad Wachsmann and, on the other, the project for a geodesic dome, with a diameter of 2 miles, proposed by Buckminster Fuller. “The refusal of architecture as the formalization of spaces” coherently and integrally completes its cycle.

Opening image: from Domus 638, April 1983