Defining wabi-sabi? Even for a Japanese person, it’s a perilous exercise, as Leonard Koren reminds us in his book Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers (1994). A fusion of two words – wabi, the solitude of one who lives in nature, and sabi, the patina of time, the beauty of transformation – this Zen Buddhist concept first took shape in Japan through the ritual of the tea ceremony, eventually expanding to signify both a craft ethos and a distinct aesthetic sensibility.

So what, then, is wabi-sabi? Translating it as “rustic” is so reductive it misses the point entirely. Without pretending to be exhaustive or overly precise, we could define wabi-sabi as a systemic order of metaphysical character, one not bound to function, but oriented toward valuing the beauty of incompleteness and transformation.

At the beginning of the 17th century, wabi-sabi began to crystallize through the tea ceremony. The bowls used by the first tea masters were Japan’s response to Chinese ceramics, glazed, colorful, technically perfect. Wabi-sabi, on the other hand, embraced rough textures, neutral tones, the traces of time, even flaws, finding in nature a source of harmony and contemplation.

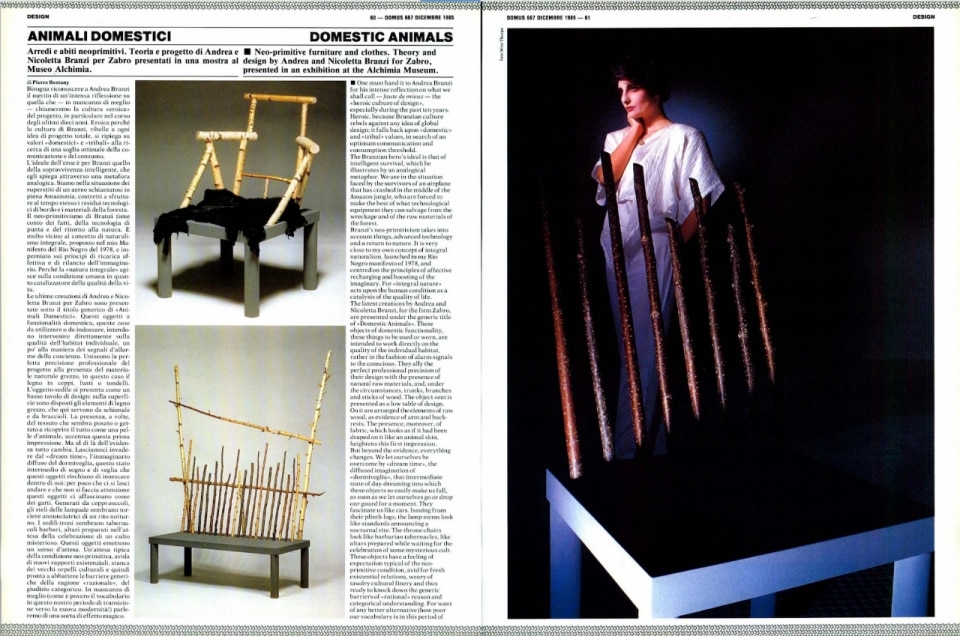

In the West, wabi-sabi has long fascinated those drawn to its quiet celebration of imperfection, to the humility of the ordinary object, and, more profoundly, to its ability to convey through an artifact the immanence of life itself. As often happens in cross-cultural translation, its journey from East to West has generated new sensitivities and creative short circuits, expanding its meanings and manifestations. The eight objects in our gallery tell this evolving story, crossing paths with the likes of Andrea Branzi, Alchimia and Paola Navone, the Campana brothers, Shiro Kuramata and Maarten Baas.