The Campana Brothers’ studio is filled with so much life that it’s hard to believe less than 20 people (and two resident dogs) work with Fernando and Humberto Campana at their São Paulo headquarters. Humberto greets me at the front door, which leads into a showroom filled with the furniture pieces that have made the Brazilian brothers famous around the world.

A photoshoot is taking place, documenting some of the latest items in their collection. Downstairs, a team member welds together an edition of a seat that forms part of the Hybridism exhibition currently on show at Carpenters Workshop Gallery in London. A colleague rolls thin pieces of colourful foam into the studio’s renowned ‘sushi’ surfaces. And two other staff stuff fabric cushions with material offcuts that will be sewn together into sofas. Upstairs, Humberto leads me into his office, where each countertop is stacked with his ever-evolving design experiments, and we talk for an hour about what continues to make the Campana Brothers create thought-provoking work after more than 30 years in the industry.

Congratulations on your solo show at Carpenters Workshop Gallery in London. I’ve seen the photographs of the exhibition and it looks like a beautiful presentation.

Oh, thank you. We even chose the colour for the walls, inspired by that animal. [Humberto points to a blue metallic crocodile standing on his office shelf.] The blue paint, metallics… it contrasts with the bronze pieces we’ve made and gives them more life.

The exhibition is an evolution of your Hybridism show at Friedman Benda in New York in 2017. Usually a solo show is very distinct. What was it that you still wanted to create and talk about in Hybridism that made you continue this line of thought – and title – for the current show at Carpenters Workshop Gallery?

I think we are storytellers, you know? After 35 years working as designers, doing things connected to functionality, my brother and I decided to experiment with things that affect us, to do something more personal. It’s a bit like vomiting what is happening in the world. To have this president that Brazil has, Trump, deforestation, climate change… those things affect me a lot. And I’m not the kind of person who goes onto Facebook or Instagram to protest. I hate that. My protest is through this[his work]. So I stay here [in his studio] and imagine the world becoming hybrid. In the future, people who are hybrids will survive because we need the flexibility to adapt. Of course this is metaphorical, but the changes are so fast and things are happening at such a velocity that if you don’t adapt as a hybrid, you’ll vanish. We’re still working on the same subject but it’s more curated and surrealistic.

So you view hybridism as a positive thing? You’re seeing all the negativity in the world, but putting it into your pieces and letting it emerge in a way that you see as a solution?

Yes, of course, as a solution. My brother and I always propose things, using different materials. In a way, this show is very dark but has a certain beauty with the bronze, because the main material that drives the whole exhibition is bronze, combined with other elements and materials.

[Tracy holds up a table leg lying on Humberto’s desk, made up of various miniature animal shapes stuck together.]

This is from the ‘Noah’ series that forms part of Hybridism, right?

Yes, these are the legs for a marble table. I like to stay here [in his office], gluing things together. I’m still in love with this way of working.

Did you choose specific animals, and are they in pairs like in the biblical Noah’s Ark?

No. The idea is funny. Because I travel quite a lot, whenever I’m at the airport I stop at those shops that sell little plastic or plush animals. I bring them here and cast them, and then I start to create the object. Now I’m casting in charcoal. This piece is going to look like thisonce cast. [Humberto picks up a table leg already cast in charcoal.] When I saw this [final product], I thought, “Look, this is like Noah’s Ark!” Then I started creating the story behind it. This is hybrid – when I create two animals or an animal with two heads. Then I asked myself, “What drew me to create the hybrid?”, and I realised it was the anger toward what is happening in the world today. So I pulled a story together. I don’t approach things in the sense where I say, “I’m going to create a show called Hybridism.” Rather, things start to happen naturally. Like Bruno Munari says: “Da cosa nasce cosa” [one thing leads to another]. And then the story became about Noah’s Ark and how it was built to preserve the animal species, because we are at a point again, on this planet, where we are looking for solutions. The plastic in the ocean, the droughts… we are facing serious issues all over. It’s a moment where another ark needs to be created – an ark to the moon or Mars.

Your fictitious ark would obviously include the Pirarucu fish, whose skin you’ve been working with as a material for some of your Hybridism pieces. I know this is part of an NGO you’re supporting that works with locals who farm this fish as an alternative to cutting down trees as their method of earning a living. What is it that you are enjoying about working with this material?

The company that works with the community in the Amazon asked us to promote this. Normally they do shoes and handbags but they’ve never worked with furniture, so we’ve pushed the material to create a new upholstery from Pirarucu leather. It’s part of the work we do with the foundation we have created [Instituto Campana], where we promote development within communities, and I like to be part of such things. The future of Estudio Campana will go in this direction – working with communities, teaching, giving workshops. Today I’m going to the countryside to do a workshop with homeless people who have problems with drug addiction.

Are you offering them new skills?

A skill, yeah, by explaining it through my own experience. I was a lawyer before; I gave up law; and then told myself I’m going to make a living with my hands. In the beginning I had a friend who commissioned me to do frames for mirrors. He lived in Bahia so I used seashells I picked up on the beach there to make the mirrors. That was my beginning.

So it’s always been about the material.

And the hands. This community I’m going to today is based near a brick factory. When I first went there I didn’t have a clue what to do with the group. But then I saw the brick factory, and asked the owner to give me bricks in a humid state, and we did this workshop with them.

[A colleague brings in some vases developed from the bricks.]

I do things with flexibility. I guess this is the magic. It also has a sense of hybridism. I told them to put all their anger, hate, hopes and fantasies into these vases, so they started banging the humid bricks down. [Humberto shows how the form at the bottom of the brick vases transformed under the manipulation to create new forms.] I try to transform things. These are now sold in museum shops. We do these sort of things with other communities, too. And every month we bring kids here to the studio from the favela and give them workshops. The idea of the studio and Instituto Campana is going in this direction.

I know you’re rescuing skills and keeping traditions alive by using artisanal knowledge in Brazil. How is this being done?

We bring craft to the level of design. I push the people who work here to better their skills of crafting. For instance, the ladies who made the armchair you’re sitting on… they came from fashion. So I taught them how to use their skills on another project – we made pillows and then attached one to the other to make the chair.

Passing on skills to the next generation…

That’s the idea. To maintain our legacy. Even creating a small museum with our foundation. We have made a lot of things, and they’re all in storage.

Do you weave yourself?

I use artisans. I don’t try to change their technique. I just try to give another ‘plus’ to their technique. Like in the TransPlastic collection where we weave plastic with the rattan weave. Someone who’s used to weaving a fruit bowl all their life can now weave with plastic. There’s another project we did three or four years ago with embroidery. We were invited to work with an NGO in the north-east of Brazil. What those ladies normally do is embroider tablecloths and napkins and I gave them another challenge. Why not embroider their faces in lamps?

Do you see a material and say, “What can I do with this?” or do you say, “I want to create a chair, so what material will I use?” What’s your approach?

Nowadays it’s both. For instance, for those [Humberto points to wool-woven screens perched on the counter behind Tracy], I imagined an installation where someone would weave with colourful cords. I’d like to create a room full of these hanging pieces. And I’m keeping all of thoseleftovers [Humberto points to a pile of appliance-protector Styrofoam on the floor] because I want to create a sofa with them. Everything happens in this way.

I think it’s so wonderful that you’re able to create value out of things that people would not even look at again, or would normally throw away.

This, I guess, is my richness, my treasure. Nowadays more and more people are looking at alternatives but me and my brother were the ones who started this – not a revolution, but this consciousness to create the fake diamond. It’s like we’re forming a diamond, but it’s fake.

Who needs diamonds anyway?

Yeah, exactly! [Humberto laughs.]

I know you’ve used plastic before, and now the world is saying plastic is bad. Has your approach to the material changed?

I think the problem with plastic is education. It’s been useful but we have to take care about things like not throwing it in the ocean. And reuse of course. Science today is much more advanced and we can create biodegradable plastic. We designed shoes for Melissa, a Brazilian company that works with plastic. In order for us to be involved in the project, we asked them to use the maximum amount of recycled plastic possible. So now 30% of our shoe is recycled. And the idea is to get this to 100%. I’m also working with the British company BOTTLETOP. They’ve invited me to work with 3D printing, using resin made from the plastic waste in the North Sea. The idea is to work with this plastic to make a small bench. I love when people invite me to be part of projects like this, offering solutions.

For Salone del Mobile in Milan this month, you’re working with Melissa again on a crochet shoe and bag. You’re actually doing a lot of things for Salone, collaborating, too, with Louis Vuitton, Artemide and Nodus/Il Picollo.

We’re actually designing five pieces! Sometimes I don’t create anything for Salone but sometimes it’s a way to … I don’t know… things start happening in my head and it comes here [Humberto points to his gut]. You know, I’m very ‘stomach’.

With all of these brand collaborations you’ve done over the years, what do you see as the greatest value?

They’re important. Designers can bring new ideas, new ways to educate big companies how not to waste so much, and can send messages through these companies. Like with Melissa, and using more recycled plastic. With Louis Vuitton, the first cabinet we made for them – the Maracatu – was all made from the offcuts of Louis Vuitton [fabric]. And when Lacoste asked us to design this special-edition shirt [Humberto gets up to show Tracy a shirt framed in the office passageway, made entirely of tiny, green Lacoste crocodile fabric emblems sewn together], we had it made in a favela through another NGO we work with because we wanted it to be a social project. We had 2,000 Lacoste crocodiles made by this association and it’s all handmade. We like to promote such things.

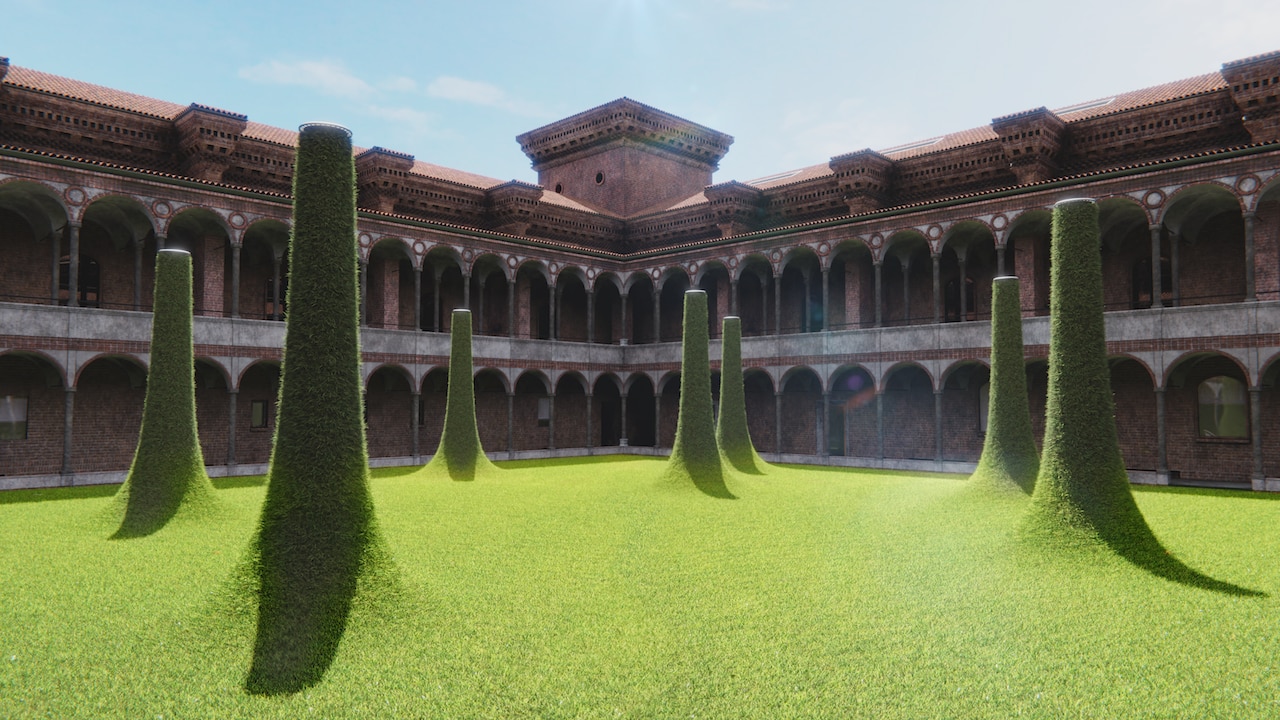

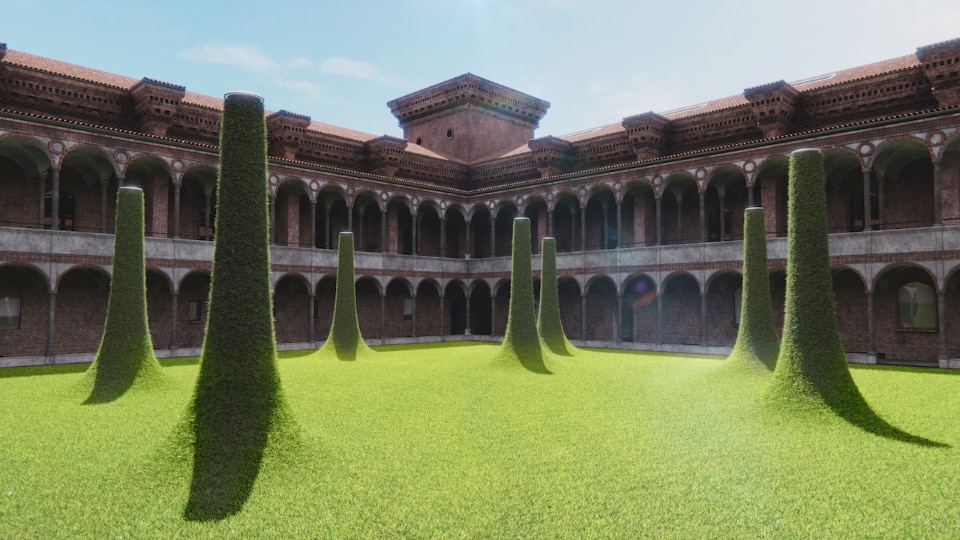

For Salone del Mobile, you’re also doing the Interni installation for Human Spaces 2019. I’d love to hear about your thinking of combining nature and architecture in this public installation at Cortile della Farmacia.

The installation is a creative dialogue with the architecture’s arches. We inverted the architecture to create the opposite [inverted arches] with nature, with five-metre-long wooden columns covered in the same grass that is in the courtyard, and, at night, they light up. The title is ‘Sleeping Piles’. It’s a joke with ‘sleeping pills’ because it’s a place to sleep, to relax, to have no noise. A silent place that one can use like a bench [using the pillars to lean on]. I’m very anxious to see this, as it was a daydream, but I think we can construct beautiful things with nature.

- Designer:

- Estudio Campana

- Where:

- Via Festa del Perdono 7

- Opening dates:

- 9-14th April

- Venue:

- Milan Design Week 2019