Late 1950s – the worlds of industry and technology stood at a monumental crossroads: the shift from a mechanical culture to an electronic one. This transition was both delicate and, in many ways, risky. Mechanical culture still felt robust and efficient, and resistance to change was deeply rooted on both cultural and industrial fronts.

It required vision and foresight to grasp the urgency – and the inevitability – of such a transformation. In Italy, Roberto Olivetti (eldest son of Adriano, the legendary founder of the Ivrea-based company) and Ettore Sottsass (appointed designer for Olivetti’s new Electronics Division in 1958) were among the few who understood this shift. They were also among the first to recognize the need to radically innovate the tools of office work in a rapidly and wildly transforming society.

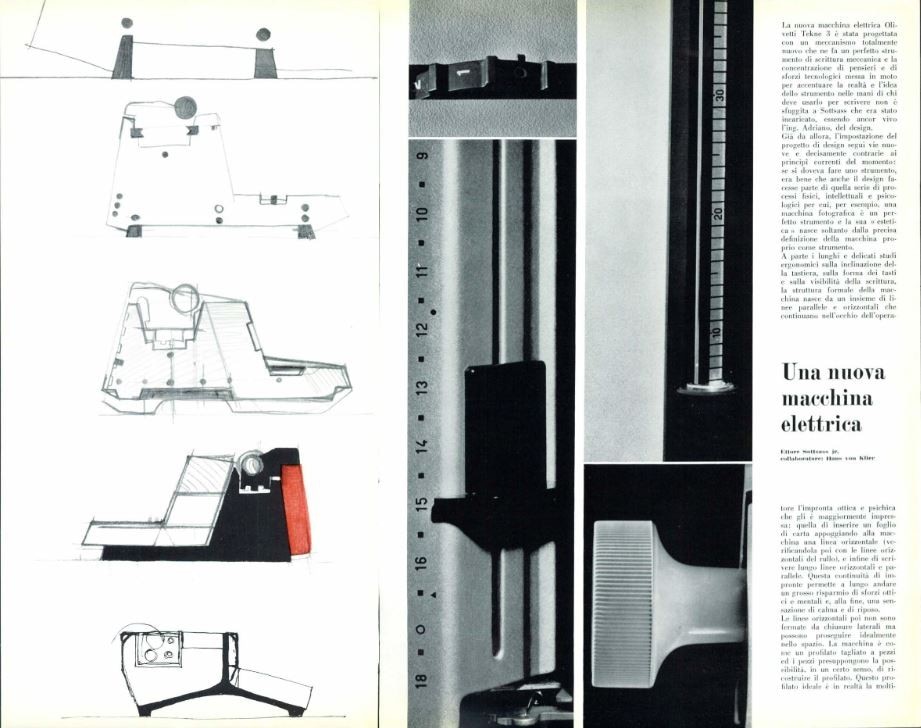

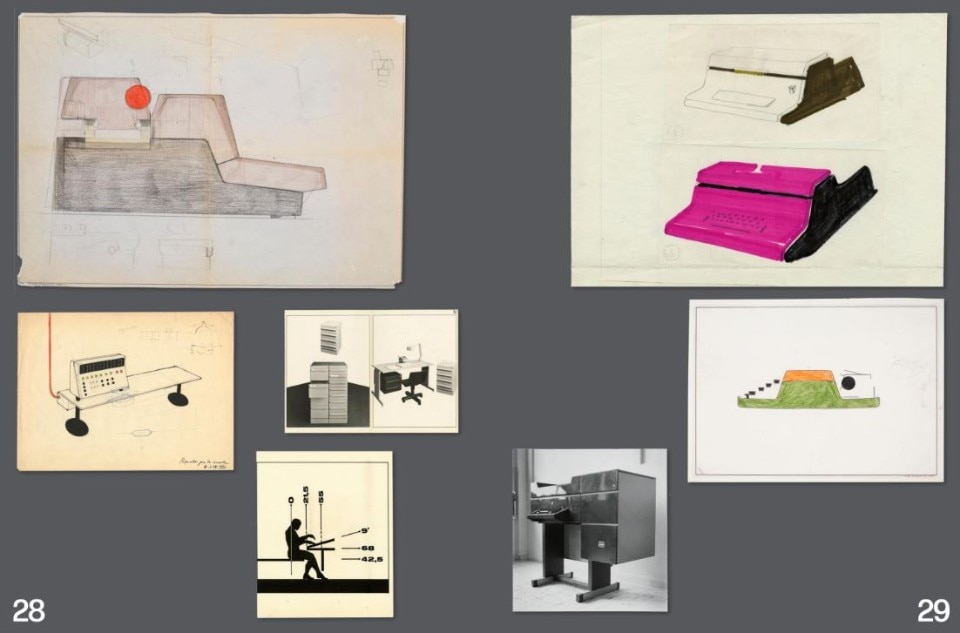

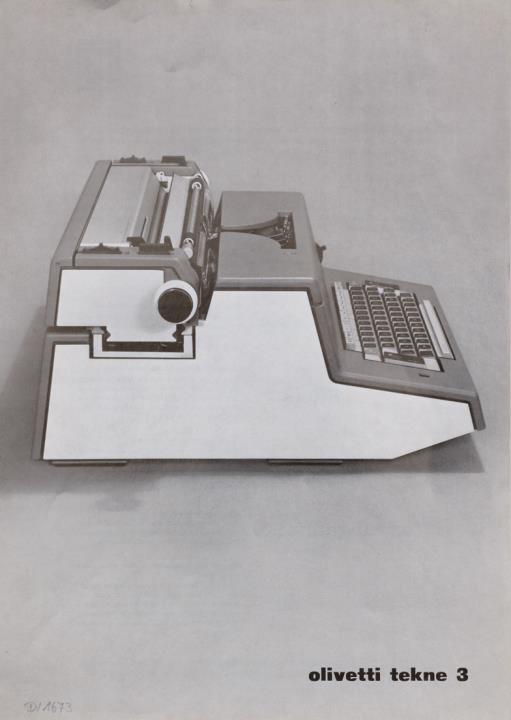

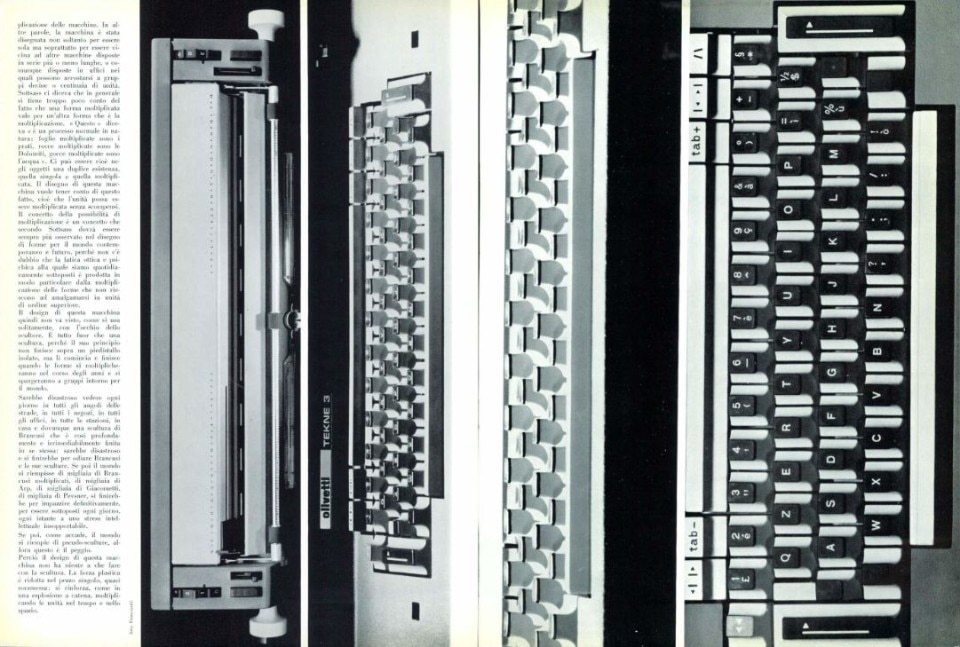

It was within this context that the Tekne 3 electric typewriter was created in 1964. This groundbreaking machine was conceptually linked to Olivetti’s earlier cult object, the Lexikon 80, designed by Marcello Nizzoli.

However, the Tekne 3 pushed innovation forward on both technological and aesthetic fronts. Engineer Rinaldo Salto developed advanced technical solutions, harmonizing the motor’s interaction with the levers through a sophisticated system that enabled a theoretical speed of 840 keystrokes per minute –significantly faster than the 600–650 keystrokes achieved by the fastest typists. It also allowed for the simultaneous printing of up to 20 copies. Salto further engineered a “memory and selection” system capable of recording keystroke inputs and executing them in a set order at a constant speed, smoothing out any irregularities in the operator’s typing rhythm. The keyboard, as the primary human-machine interface, was meticulously studied for ergonomics: positioning, tilt, and movement of the keys were carefully calibrated to reduce physical fatigue and enhance the overall user experience.

The outer shell’s design was entrusted to Sottsass, who opted for a minimalist approach. He described his efforts this way: “It doesn’t have a lot of softness, nor frivolous concessions. All the effort, together with Von Klier […] and engineer Salto […] was directed towards organizing the machine’s various parts […], simplifying the composition, calming it down, aligning the elements as much as possible[…], removing all that was superfluous, and trying to present to the user’s eye a small, calm, and orderly landscape, free of distractions and deviations.”

Sottsass deliberately designs the Tekne 3’s casing to seamlessly integrate into a series, be multiplied, and designed to coexist with other identical machines in shared workspaces. In other words, the machine is designed to coexist with other machines.

Sottsass had another critical insight, drawn from his acute observations of sociological and behavioral patterns: a typewriter like the Tekne 3 – he observed – is rarely used alone; In most case it is found in offices, filled with other machines. A multiplied form gives rise to a new form: “This is a natural process: multiplied leaves become meadows; multiplied rocks form the Dolomites; multiplied drops make water.” For Sottsass, objects can possess a dual existence – the singular and the multiplied. He argued that this typewriter shouldn’t be seen as if it were a standalone sculpture: “It would be disastrous,” he notes, “to encounter a Brancusi sculpture – so deeply and irreversibly complete in itself – every day on every street corner, in every store, office, station, or home. Such ubiquity would lead to resentment, and one would eventually come to hate both Brancusi and his sculptures.”

It doesn’t have a lot of softness, nor frivolous concessions.

Ettore Sottsass

Thus, Sottsass deliberately designs the Tekne 3’s casing to seamlessly integrate into a series, be multiplied, and designed to coexist with other identical machines in shared workspaces. In other words, the machine is designed to coexist with other machines arranged in series of varying lengths or placed in offices with dozens or even hundreds of similar units.

For Sottsass, the Tekne 3 was not merely a typewriter; it was a design manifesto reflecting his creative vision. To him, designing is not just about creating an object; it meant imagining systems and contexts that respect human needs, easing their struggle and enhancing their experience.

With the Tekne 3 Sottsass demonstrates that design never just about aesthetics or functionality; it is a dialogue with the environment, society, and cultural tensions of the time. In a similar manner, designers serve as mediators between industrial rationality and human complexity, always striving for a balance between order and freedom.

Opening image: Olivetti Tekne 3. Courtesy Olivetti