Prefabrication, modularity, research on materials, environmental sustainability and the importance of reduction – elements that lead to fundamental research on the needed forms – sound obsolete in times when the prevailing architectural (and not only architectural) aesthetic is that of the “one-off”. These words are currently featured in the work of a Japanese architect who grew up with the sophisticated theories of the New York Five School. His name: Shigeru Ban, who studied in the United States and underwent the fascination of Mies. We can imagine that his research on the language of structures developed precisely out of his encounter with the modern master, and that then, driven by the natural Japanese predisposition toward fragility, he turned his attention to materials that were less authoritative and less definite than steel. “When you invent new materials and structures, you can succeed in making new types of space. Instead of simply using the design or the style to create a different type of space, I want to develop the material – and the structure – by using its own character.”

The story goes that Shigeru began experimenting with materials that were unusual in architectural building in 1986, while designing an exhibition on the work of Finnish master Alvar Aalto that the New York MoMA was planning for that year. Half by chance, half propelled by the innate Japanese attraction to the sensual beauty of paper, Shigeru Ban decided to transpose an industrial product (the cardboard tubes used in the textile industry as cores for bolts of fabric, hidden from sight without the least regard for their intrinsic beauty) to the world of construction, using them as building materials. Since this was a technique with a character of necessity, Ban sought the collaboration of the great Japanese structural engineer Gengo Matsui, who had dedicated many years to exploring the static qualities of traditional Japanese materials such as bamboo and wood. Experimentation on standard cardboard tubes with different sections, thicknesses and sizes allowed him to develop an extensive and complex language of architectural shapes with an uncommon material. In doing so, he introduced this semimanufactured material to a tradition that up until then had been extraneous to it. He enlarged his experience by creating different living solutions in relation to their context and the availability of industrial resources and local materials. Eventually, in 1993, this led to cardboard tubes being authorised by the Japanese Ministry of Construction as a structural material that may be used in permanent buildings that fall under Article 38 of the Building Standard Act. In addition to the famous PTS (Paper Tube Structure) experience, Shigeru Ban’s research on industrial materials can be divided into other categories of “inventions”, such as the pre-compressed reinforced concrete piles (generally made for foundations) he used as the visible columns in the PC Pile House; or the industrially produced furniture he used to make the robust walls of the Furniture House; or the curtains running all around the perimeter of the Curtain Wall House, making a moveable facade; or the containers he used for the Container Structure in the Nova Oshima Showroom. Such projects must have prompted two Scandinavian manufacturers, Artek and UPM, to commission Shigeru Ban to explore the qualities of another unusual material: a combination of plastic and paper used in the packaging industry. The two companies asked Ban to design a pavilion that was located in the garden of Milan’s Triennale building during the last Furniture Fair.

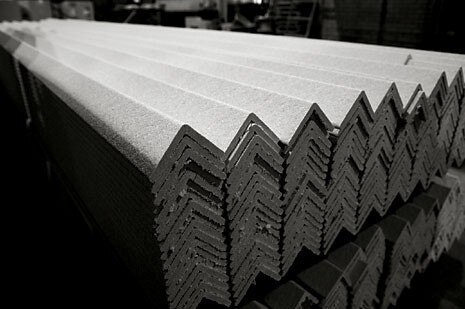

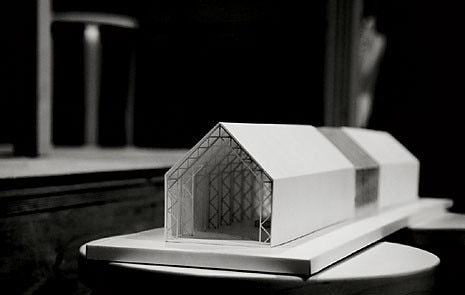

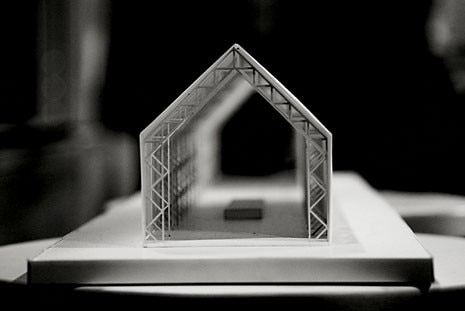

Available in very large quantities as a by-product of one of the most widespread labelling systems in the world (the ones used in big distribution systems for merchandise identification), the material is particularly suitable for construction. It combines the qualities of paper with those of plastic, making it a warm material that softens sound and has a waxy, tactile finish. In the fluid space of the Artek pavilion, Ban used standard L-profiles produced by the Finnish manufacturer to build a skeleton of trusses that lend rhythm to the regularity of the space and openly show its construction logic. After all, Mies was the man who maintained, “When clear construction is elevated to an exact expression, that is what I call architecture.”