‘When I look back at the last 25 years, it seems to me very much that I’ve been doing what I felt like doing for 25 years, and it doesn’t seem to have much to do with graphic design’, says Peter Saville, who, at 47, is one of the best-known and still (perversely?) one of the hippest designers and art directors in Britain.

His body of work includes some iconographic stuff, from New Order album covers to Yohji Yamamoto catalogues and art gallery identities. But Saville himself is perhaps the strongest image of all – the creative about town, the louche Peter Pan. ‘Cultivating his playboy image’, says someone who has been a very close friend, ‘is Peter Saville’s major occupation.’

Saville now lives in London, but he started out in the north of England, a child of privilege, clever and obsessed by model car racing. With two older brothers, he sat out the 1960s as an observer, but was a teenager in the 1970s, when his aesthetic sensibilities were moulded by the cool glamour of Roxy Music and his hero, Bryan Ferry. By the time he reached art school in 1974, he knew that image was everything.

His first poster, for a radical new Manchester club called The Factory, could be seen as a mission statement. At a time when the frantic cutup type and fluorescent colours of punk were the order of the day, Saville had produced ‘the coolest, least homemade-looking’ piece of work he could. An assemblage of heavy rules and carefully kerned sans serif type, it unites the classical and the modern in a way that would become Saville’s trademark. Its implication was that you don’t have to reach all the people, just the right people.

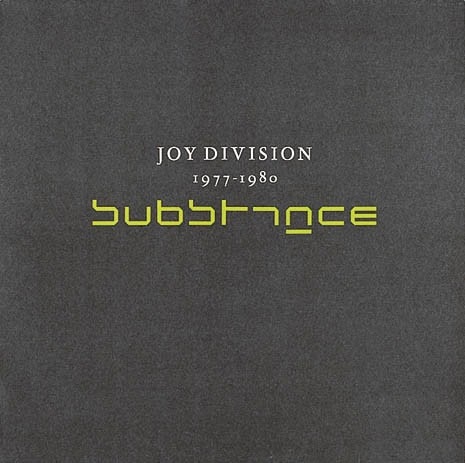

Away from the cost and competition of London, Saville was free to innovate. With Tony Wilson and Alan Erasmus, he became part of a new local record label called Factory Communications, creating the cover art for bands producing the new electronic northern sound, though Saville’s relationship seems to have been less with the music than with the scene, which attracted young, arty trendsetters. He satisfied their demands and curiosities with artwork that used existing imagery in a new way, and he paid lip service to the new technologies that were informing their world.

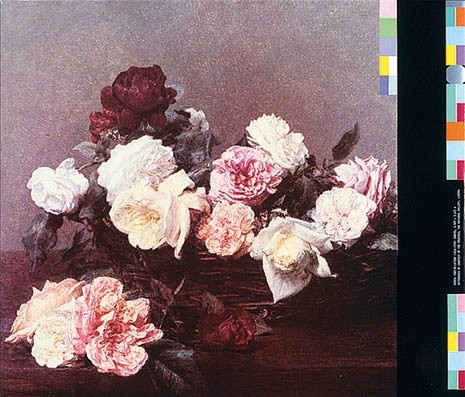

Thus a flower painting by Henri Fantin-Latour decorates the cover of New Order’s ‘Power, Corruption and Lies’, while the group’s 1983 ‘Blue Monday’ single cover is die-cut to look like a floppy disk. ‘I’d discovered a floppy disk for the first time when I went to visit them in the studio. The track is an almost entirely sequenced seven minutes, and the equipment plays it better than they do, so it just seemed right’.

Nonetheless, Manchester in the early 1980s was a marginal place, and Saville had to set his sights on London. People liked his style, the tight ensemble of provocative image and excessively edited type; his combination of romanticism and technology better mirrored what was happening in fashion than anything else around it, but work came slowly.

Saville is a professional collaborator, often working with people whose habits couldn’t be more different from his own wilful ways. His perfectionism makes him unable to meet almost any deadline you’d care to give him, while his inability to either go to bed at night or get up in the morning seriously reduces his aptitude for office work, or for attending meetings before three in the afternoon. ‘He strives for perfection’, says fellow designer and ex-college friend Malcolm Garrett. ‘He’s been known to rub out notes he’s taken talking to someone on the phone and rewrite them better and more neatly. It’s an ideal to strive for’.

Saville’s real introduction to the fashion world came in 1986 via the photographer Nick Knight, who describes the designer’s lack of punctuality as ‘the most singularly annoying thing about him. But not the most interesting’. Knight had just completed a campaign for Yohji Yamamoto, and Saville had just been devastated by the end of his relationship with a girl called Rachel. ‘She was at Cambridge and a model. She brought together everything I wanted’, he says. Knight led him right to the heart of fashion, working on catalogues for Yamamoto, Jil Sander and Martine Sitbon.

When Pentagram, the international design group, invited him to become a partner in 1990, the cash-guzzling playboy couldn’t say no. At the time Saville was disillusioned. ‘Design had become the new advertising, an end in itself’. And there was a biting recession. But the relationship was a disaster. ‘They didn’t try to understand what drove him.

They thought he was a flake and a charlatan’, says Malcolm Garrett. The relationship quickly unravelled. His subsequent time at the design firm Frankfurt Balkind in Los Angeles was briefer still. Saville’s life since his return to Europe has been littered with interesting projects: almost imperceptible updates of fashion house logos; work with Nick Knight on his interactive fashion and art web site, Showstudio; album and CD covers for chic young bands such as Pulp and Suede. But Saville is still dodging the cracks, perpetually homeless and staying in friends’ houses, which, however glamorous, are never home. He falls in and out of insolvency, hiring and turning away staff.

He is currently staying in the house of a fabulously successful former model and a fashion designer in West London. The four identical pairs of white jeans have to be moved whenever the couple decides to return. His east London studio in Ironmonger Row has no phone.

But there is a logo redesign for EMI to keep the wolf from the door. A book of his greatest hits is about to hit the presses and an exhibition at the Design Museum will serve as a further reminder why Peter Saville is one of Britain’s greatest arbiters of elegance. ‘By the late ’90s, when the next big thing after me had run its course, there was a reassessment and I was elevated to the hall of fame’, says Saville. ‘At least I still had integrity. I wasn’t doing nappy wrappers for Mothercare’. After which he lights his tenth cigarette of the hour. ‘It helps my sense of well-being to be regarded like that. I say to myself, “Peter, you haven’t got any money, you don’t live anywhere, but are you happy who you are?” And I say, you know, I’d rather be Peter Saville than anybody’.