“Much of what is painted on South Asian vehicles serves as a good luck charm for the driver. So, I must admit I was surprised to see several trucks in Nepal painted with scenes from the movie Titanic. That doesn’t exactly seem like good luck to me.” With these words, Canadian photographer Christopher Herwig—known worldwide for his documentary work—begins telling Domus about his journey through South Asian countries.

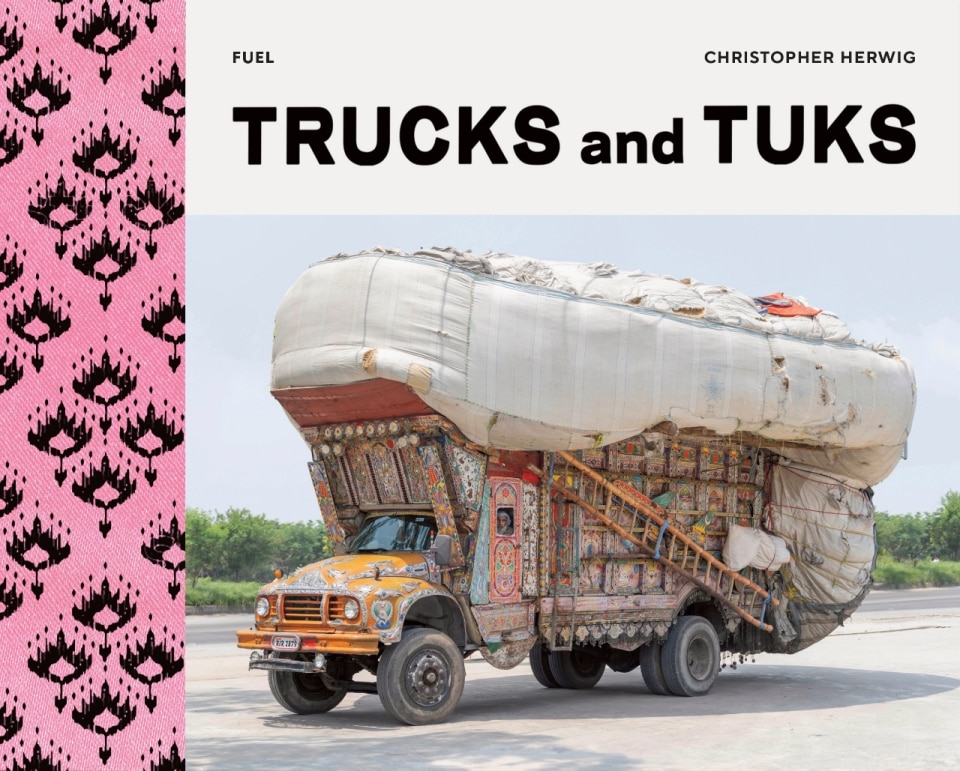

When we asked him about his acclaimed work on Soviet bus stops in the former USSR, Herwig was in Sri Lanka, working on the editing of his latest book, just published, entitled Trucks and Tuks: Decorated Vehicles of South Asia. It is a portfolio documenting the lively decoration of vehicles—particularly trucks and tuk-tuks—as a genuine form of vernacular art, expressed in different ways in each country.

Over the years, these utilitarian vehicles have become canvases for vibrant, expressive artworks meant to reflect the drivers’ identities. In Herwig’s photos, we see national heroes such as Pakistan’s founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah, but also pop culture figures like Joker, Batman, and Bruce Lee, testifying to foreign influence. Writer and critic Riya Raagini explains in the book’s introduction:

“That vehicle art continues to evolve in unexpected directions, incorporating and juxtaposing influences from numerous, sometimes seemingly contrasting worlds, is perhaps mainly due to the small karkhanas (workshops) and the skill of their artists. With no formal artistic education (in most instances) they are taught on the job, training under an ustad (master artist). Simultaneously they learn to develop their individual imagination using ephemera from their immediate surroundings (posters, picture books, calendars etc.) as inspiration. ”

That is why it is not difficult to come across images of architecture such as the Taj Mahal, one of the symbols of India and all of South Asia, but also the more distant Tower Bridge in London or the Sydney Opera House by architect Jørn Utzon, belonging to very different continents and cultures. Herwig tells Domus that he had the chance to meet some of the artists, to see them create works of art in a matter of minutes. He couldn't help but take advantage of the photographer, who had a travel crate painted instead of a truck.

For a driver, the truck isn’t simply a carrier of goods, but their very own dulhan (bride) with whom they spend the majority of their time, finding solace in moments of monotony and loneliness.

Riya Raagini

But why fill vehicles with recurring figures and motifs? The reason has ancient roots, dating back to before motor vehicles spread in the 20th century, when sajavat (decoration) was applied to transport such as boats and carts. Today, trucks and tuk-tuks roam the streets of South Asia loaded with meaning, often displaying illustrations that outsiders struggle to understand—like in India, where some vehicles bear the inscription “Use dipper at night.”

“I thought it meant lowering the headlights or using low beams not to blind oncoming drivers,” Herwig explains. “That’s partly true, but then I discovered it was also a safe sex campaign. The goal was to sell a condom brand called Dipper Condoms and curb the spread of sexually transmitted diseases among truck drivers, who often spend time with prostitutes.”

Many vehicles also feature the same wedding symbols found on houses, because a truck is not just a means of transporting goods but represents the driver’s dulhan—his bride. “I admit I had some prejudices about truckers, thinking they would necessarily be aggressive people I should be cautious around,” Herwig recalls when asked how drivers reacted to the attention he gave them. Against all his expectations, “they turned out to be welcoming and generous; they often invited me to dinner or prepared tea, even though many earn little, work long hours, and don’t own a car themselves.”

With new restrictions being introduced, on top of not owning their own vehicles, many drivers will likely also have to give up decorating them. While truck art has thrived as a spontaneous form of expression, recent regulations in different countries are now undermining the entire practice, as Herwig’s book explains. The justifications vary: the images could distract other drivers, cause offense, or fail to comply with traffic codes. For now, truck art is still rolling on South Asian roads, but Herwig’s photographic work—showing not only the art itself but also the drivers “proud to display their vehicles,” as he says—may end up being the legacy of an artistic movement we will slowly see disappear.

Opening image: Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Photo by Christopher Herwig from Trucks and Tuks, edited by FUEL, 2025. © Herwig / FUEL